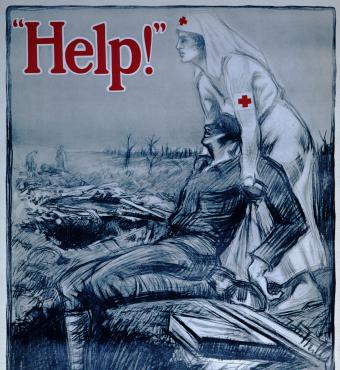

It’s a disturbing thought that any military force would seek to blame battlefield failure on the distraction of resources generated by the provision of medical care for severely wounded service personnel. As a historian, I sought to find examples of this in the past. Even in times where humans lacked the knowledge of anaesthesiology, antibiotics, blood transfusions, and other techniques that we would today consider standard practice in both civilian and military medical contexts, I have been unable to find an example in the modern era where defeat is ascribed to the deflection of resources from the fighting force to care of the wounded.

Indeed, military historians of the twentieth century have concluded very much the opposite. In Professor Amnon Sella’s definitive analysis, The Value of Human Life in Soviet Warfare (Routledge, 1992), he demonstrated that Soviet attitudes to its military-medical service, its own prisoners of war, and the ethos of fighting to the death had changed completely from Czarist times. The Soviet military throughout its history was much less ready to tolerate massive sacrifices of its men than had been assumed by Western strategists. Although Soviet military medical capability was not advanced, it was extensive and highly visible to all service personnel (whilst the stretchers bearing the badly wounded to medical facilities at the rear of the Eastern Front were usually pulled by reindeer or large dogs, they could be seen to be operating as part of an effective evacuation process). Sella’s interpretation was that utilitarian-military logic, rather than compassion, dictated this priority on medical care for the purposes of the maintenance of fighting morale. Whatever the rationale, for the modern soldier, the knowledge that if they call out “Medic,” they will receive some kind of response is key to their own or their comrades’ ability to fight on.

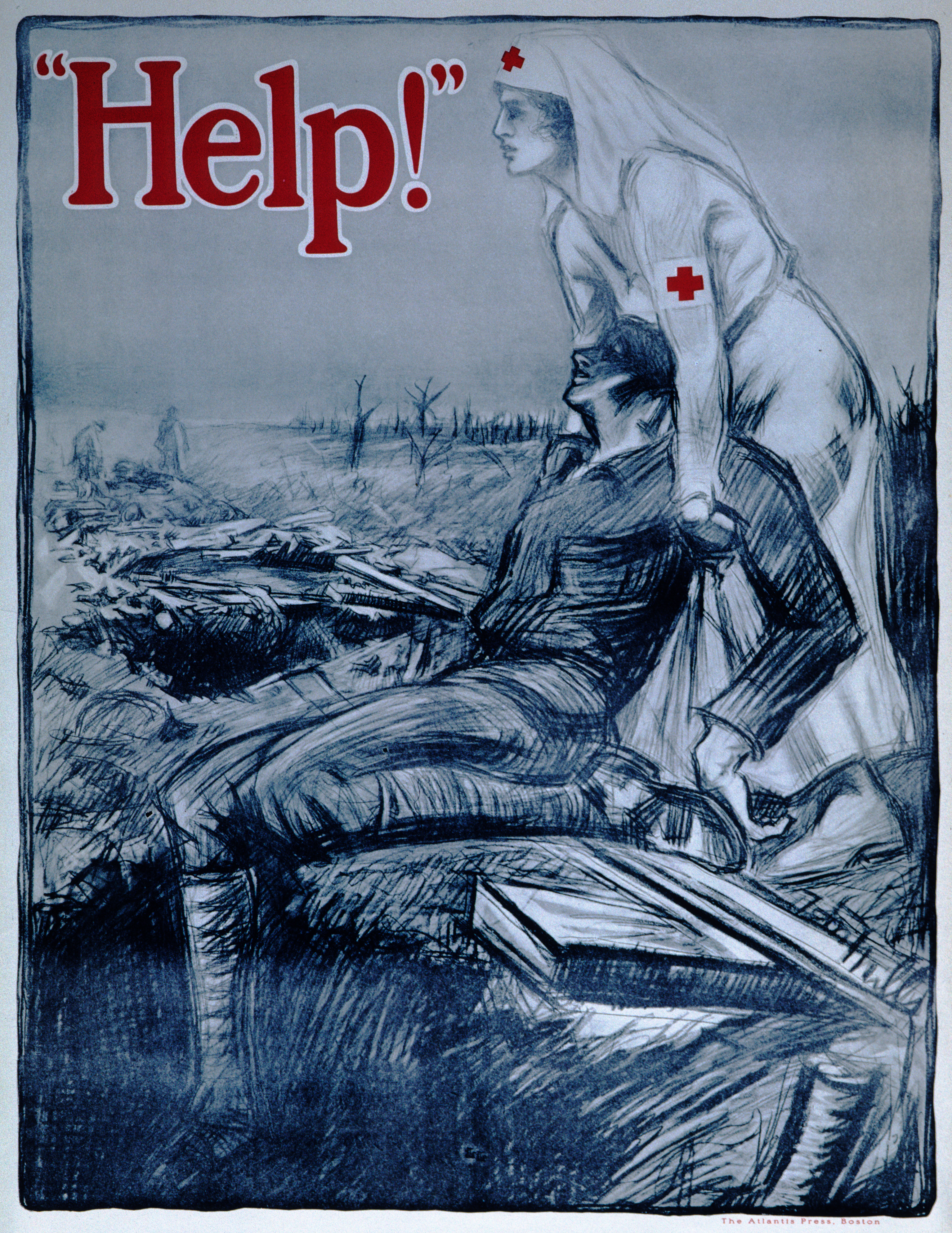

In order to fully understand the fundamental importance of the provision of medical care to fighting troops, it is necessary to go beyond the battlefield to the earliest point of engagement between each individual potential service member and the military command structure. The armies of both the UK and United States are volunteer services. No one joins up without having made a decision based on a range of factors (e.g., family tradition, military support for further education, employment prospects) but underlying them all is the understanding that the best available medical care will be available to both them and their comrades in the event of battlefield wounding. As one of the leading U.S. military medics recently put it during the Excelsior Surgical Society Conference in Rome, “more than anything else, what helps people sign on the dotted line is to know that if you have a chance of surviving [a severe injury] we’ll do whatever it takes.” Without that foreknowledge of medical expertise and effort, it is likely that fewer volunteers would sign on the dotted line, and therefore be available to participate on the battlefield at all.

A similar principle applies to the presence of medical personnel in the military. They also join up for a range of reasons. Prime among them is the opportunity to gain and apply specialist knowledge to support their fellow service personnel through the severe challenges of surviving traumatic injury, whether at point of wounding as a combat medic, or in a Role One facility as a combat surgeon. In both the U.S. and UK, consolidating the knowledge and practices of recent battlefield medical experiences so that they may be applied quickly and effectively in the next setting (either the Global War on Terror or Great Power Competition) is a key component of military medical practice. Were the medical priorities of the U.S. military to change in future conflicts, fewer of them would seek this career pathway and ultimately there would be fewer qualified personnel available to engage with either the sick or the severely wounded on future battlefields.

It is hard to see what strategic advantages any reduction in deployable advanced casualty care would afford the military services. Instead, history suggests that there are significant disadvantages: reductions in numbers of service personnel available to deploy, reductions in available medical care across settings, and the absolute threat to the maintenance of fighting morale. Indeed, it is difficult to envisage a more damaging hazard in a military setting than a wounded soldier calling “Medic” and silence being the only response.

Dr. Emily Mayhew is a military medical historian specializing in the study of severe casualties, their infliction, treatment, and long-term outcomes in 20th and 21st-century warfare. She is a historian in residence in the Department of Bioengineering at Imperial College London, working primarily with the researchers and staff of the Centre for Injury Studies.