- History

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

During the past few weeks, the Syrian crisis entered a third phase in its evolution. The transition to this new phase has, among other things, exacerbated the danger of spillover into neighboring countries and of a breakout of a regional war emanating from the Syrian civil war.

The Syrian crisis began in March 2011 as a series of peaceful demonstrations mostly in the southern and eastern parts of the country. The regime’s efforts to quash the demonstrations were to no avail and they spread into other parts of the country. The violence used by the regime against the demonstrators turned the confrontation between regime and population into an armed conflict. In time, a series of local militias developed as well as a dissident political leadership residing mostly out of the country.

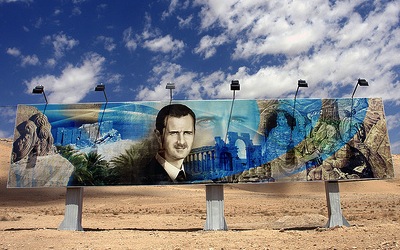

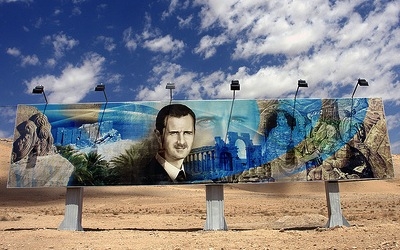

Photo credit: james_gordon_losangeles

After a relatively short period, a second phase began during which the crisis turned into a full fledged civil war. The war did not remain a domestic Syrian affair; external powers such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and to a lesser extent the United States and its West European allies began to support the opposition, while Russia, China, and Iran became the regime’s most important external supporters. The Syrian civil war thus became a war-by-proxy between Iran and its rivals on the regional level and a new arena of Russian-American rivalry on the international one.

Militarily, the conflict between the regime and the opposition could be described as a draw: The rebels took over large parts of the country but lacked the military capacity to defeat the regime. The regime, in turn, could not defeat the opposition but was able to retain its control over Damascus and the central institutions of the state. This state of affairs lasted for almost two years, exacting a high price in casualties and destruction.

More recently, several developments converged to transform the nature of the crisis. Russia and Iran have dramatically increased their investment in supporting the regime, both having calculated that Assad’s fall would inflict an unacceptable blow to their positions in the Middle East or, conversely, an unacceptable gain to the United States and its regional allies. Russia, in addition to its ongoing diplomatic protection, has undertaken to supply Syria with the most advanced air defense systems, and additional sophisticated military equipment. Iran is now openly participating in the fighting in Syria, both directly and indirectly by bringing into the country thousands of Hezbollah fighters from Lebanon.

The Obama administration, in turn, has made it abundantly clear that it does not wish to go beyond the diplomatic and indirect military support it has been giving to the opposition, and not to be drawn into military involvement in the crisis. President Obama had drawn a red line of sorts with regard to the use of chemical weapons by the regime against the opposition, but when it transpired that the regime had indeed used such weapons, the U.S. president declined to act. The Obama administration also agreed with Russia to renew the effort to achieve a political-diplomatic solution to the crisis and to convene to this end a conference in Geneva.

The regime now feels more confident in its ability to survive the crisis. With the help offered by Iran and Hezbollah, and by using better tactics on the ground, it scored a number of military achievements. A peculiar combination of a growing sense of confidence and a lingering sense of despair have led it to take bolder action, be it additional use of chemical weapons in the face of international scrutiny or the willingness to risk Israeli intervention by transferring advanced weapon systems to Hezbollah.

It is against this backdrop that the growing danger of spillover and a larger regional war will now be examined.

The three countries most deeply affected by the Syrian crisis are Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Jordan, itself facing domestic political and economic difficulties, has been challenged by an inflow of close to half a million Syrian refugees, a number that threatens to destabilize the country. Lebanon, a country intimately connected to Syria, has been more deeply affected.

Lebanon is in fact a failed state in the sense that an organization, Hezbollah, is more powerful than the state and its army, and operates according to its own lights, and more accurately, according to Iran’s instructions. Iran and Hezbollah know that the collapse of Assad’s regime could weaken, if not totally undermine, their hold on Lebanon. They also operate on the assumption that should the Syrian regime lose its hold over Damascus, they will prepare to withdraw to an Alawite state based on the Alawites mountains, the coastal strip, and the land bridge to the Shiite dominated parts of Lebanon (this explains, among other things, the fierce fighting currently underway in al-Qusayr, a strategic town on the road from that region to Lebanon).

Hezbollah’s participation in the fighting in Syria has exacerbated the tension between the organization and the larger Shiite community in Lebanon and Lebanon’s Sunni community to the point of raising the specter of a renewed civil war. The launching of two Grad missiles into the Shiite stronghold in South Beirut, the Dahiya, is a clear indication of such a danger. On May 28, General Idris, the commander of the “Free Syrian Army,” threatened to retaliate fiercely for Hezbollah’s participation in the fighting. He did not specify, but his threat implied an expansion of the war into Lebanon. Indeed, his threats were followed by military clashes in Shiite areas close to the Syrian Lebanese border.

Turkey, on the eve of the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, seemed like a powerful regional power extending its influence into Syria and other Arab countries under the banner of a policy of “new Ottomanism.” But the events of the past twenty odd months clearly revealed structural weaknesses in Turkey itself and lack of any desire by Turkey for a direct military intervention in Syria.

In 1998, the Turkish leadership threatened to launch war against Syrian if Syria did not expel Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the Kurdish-Turkish underground (PKK). Syria’s president at the time, Hafez al-Assad, took the threat seriously and in fact extradited Ocalan to Turkey where he is still in prison. In the current crisis, Turkey offers the Syrian opposition a political haven, some military help and is hosting a large number of Syrian refugees. But this policy generated significant domestic opposition in Turkey.

Furthermore, two Syrian provocations—the shooting down of a Turkish jetfighter and a terrorist act in southern Turkey—went unanswered. If the Obama administration expected early in the Syrian crisis to be able to rely on Turkey as a regional power, able and ready to carry its water in Syria, he discovered, more recently, that Turkey would actually like the United States to be more assertive and take at least a measure of military action in Syria. The recent outbreak of violent demonstrations in Turkey dramatically reduces Turkey’s ability to implement an assertive policy in the Syrian crisis.

As for the danger or prospect of an expansion of the military conflict in Syria, one scenario, that of the United States and its allies building a buffer zone or imposing a no-fly zone, seems currently less likely. President Obama is determined not to be drawn into military involvement in the Syrian crisis. As is well known, he is haunted by the legacy of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and is determined not to take the US into a third Middle Eastern war. In his eyes, to quote a cliché, “Syria is not Libya.”

The Syrian army could pose serious opposition to an invading force and Syrian air defenses could inflict damages on foreign planes imposing a no-fly zone. More importantly, Obama is horrified by the prospect of toppling Assad and remaining with a broken Syria as a U.S. responsibility. This outlook could change over time but seems to be firmly held by the administration presently.

The most serious danger of a larger war emanating out of the Syrian crisis now lies in its impact on Israel’s national security. Since the outbreak of the crisis, Israel has made a conscious effort to remain above the fray. It did respond to a number of minor incidents and while the Israeli political and national security establishments are divided over the question of the outcome most desirable to Israel, its government has kept a low profile and avoided military or diplomatic involvement in the crisis. Israel’s stake in the unfolding crisis and its eventual outcome is enormous, but the Israeli leadership is aware of its limited ability to affect the course of Syrian politics and of the negative implications for the Syrian opposition of any Israeli support.

More recently, the Israeli perspective was altered by a number of developments: the prominence among the rebels of Jihadi and Al-Qaeda linked elements; the increased role played in Syria by Iran and Hezbollah; the prospect of the Syrian arsenal of WMD of part of it falling into terrorist hands; and the transfer of advanced weapons systems from Syria to Hezbollah.

Israel defined its own red lines in Syria, threatening to act primarily if advanced weapons systems or WMD were to fall into, or be transferred to, terrorist hands. In January 2013, the Israeli Air Force destroyed a shipment of ground-to-air missiles stationed near Damascus, on its way to Lebanon. Israel refrained from taking responsibility for this action seeking not to embarrass Assad and thus reduce the danger of Syrian retaliation. In May 2013, as the prospect of additional shipments to Lebanon became more imminent, Israel acted again, this time in Damascus. The location and the visible effects of Israel’s action turned this operation into a very public act and generated threats by Assad and his regime, by Iran, and by Hezbollah to retaliate.

The sense of a crisis was enhanced by the announcement of an imminent shipment of Russian S-300 ground-to-air missiles seen and defined by Israel as “game changers” in both the Syrian and Lebanese arenas. Should Russia go ahead with the delivery of these weapons systems, and should part of this system or another advanced systems make its way to Lebanon, Israel would face a serious dilemma. Acting could draw a Syrian response, and failing to act would mean a loss of deterrence. The Russian decision can be in part seen as an effort to deter Israel, but it is primarily a move in the context of the Russian-American competition, both a substantive and a symbolic act designed to deter the U.S. from imposing a no-fly zone.

Russia’s bolder policy in Syria was met by an escalation of Israel’s position. On May 30, the Israeli press reported that Israel’s national security advisor, General Amidror, stated in a briefing to European ambassadors that Israel will not allow the deployment of Russian supplied S-300 ground-to-air missiles in Syria. In other words, he threatened that Israel will go beyond interdicting the transfer of such missiles to Lebanon, but would rather destroy them once deployed in Syria.

If the present trends continue, Israel may indeed find itself having to act yet again. Assad’s regime could respond massively, presumably by launching missiles. In theory, neither Syria nor Iran and Hezbollah have an interest in a large-scale military confrontation with Israel. Assad and his cohorts know that such a confrontation could end with the destruction of Syria’s air force and large part of its armored corps, thus opening the way for the opposition’s military victory.

For Iran and its proxy Hezbollah, important as Syria is, the main issue is Iran’s nuclear arsenal and Tehran may very well calculate that a large scale military confrontation in Syria and Lebanon could be the prelude of an attack on Iran’s nuclear installations. Hezbollah’s missiles are a major strategic threat for Israel but their main purpose is to deter Israel from attacking Iran. From Iran’s and Syria’s perspective, a more effective way of retaliating would be the launching a war of attrition in the Golan Heights. In earlier decades, wars of attrition were an effective strategy used by Syria itself as well as by Egypt to act against Israel without necessarily leading to a full fledged war.

Some of the developments reviewed and analyzed above are novel, but others are ominously familiar and evocative. During the 1969-1970 War of Attrition, the Soviet Union took direct responsibility for Egypt's aerial defense and clashed directly with Israel. In the mid-1960s, a vicious cycle of radical actions and statements exchanged between a tottering Syrian regime and Israel led the region to the Six Days War. Glaringly absent from the current scene is an authoritative U.S. policy, the only conceivable actor that can possibly put an end to the spiraling confict.