It has become fashionable in the United States to denigrate the strategic relevance of Europe, and the Middle East compared to Asia, insofar as American national interests are concerned. Asia is the locus of economic activity on the Eurasian landmass. It is home to more individuals than any other region or continent in the world. And in Asia, the United States faces a profound challenge from Communist China, which seeks to transform world order and remake it in a significantly more favorable manner to the Chinese Communist Party’s autocratic pseudo-Marxist ideological and material interests. European questions, under this reading, deserve no geopolitical answers from the United States. The Middle East ranks slightly higher in order of concern given the domestic political connections between the region and the United States, and the realities of Eurasian trade and energy markets. The United States would thus benefit by largely divesting itself of European and Middle Eastern concerns, at most leaning on trusted regional partners to carry the load, and ideally in Europe, using a series of inducements to reorient Russia, the third major power in the Eurasian geopolitical equation, away from China.

This reading of European and Middle Eastern realities in relation to American interests is largely incorrect. The Eurasian landmass is an integrated strategic and economic entity. Any strategic competition over the Eurasian landmass that attempts to separate it into discrete regional dynamics will ultimately fail. The Middle East and its Mediterranean tendrils are the maritime nexus between Europe and Asia, the hinge of the world crisis that is now well underway. This hinge will only increase in importance over the coming five years as the world crisis accelerates.

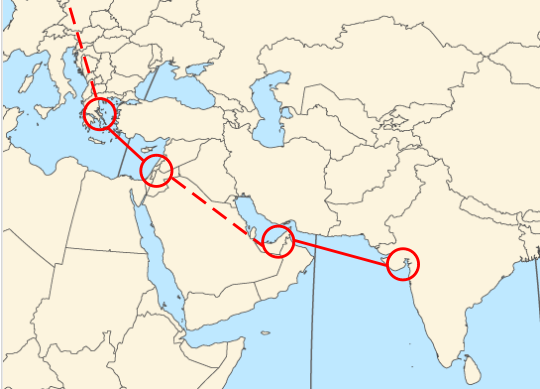

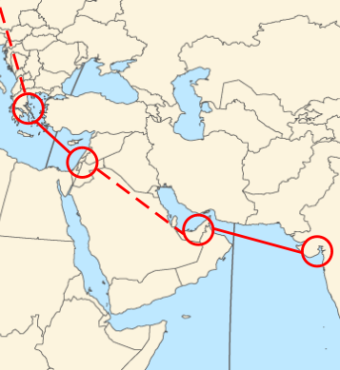

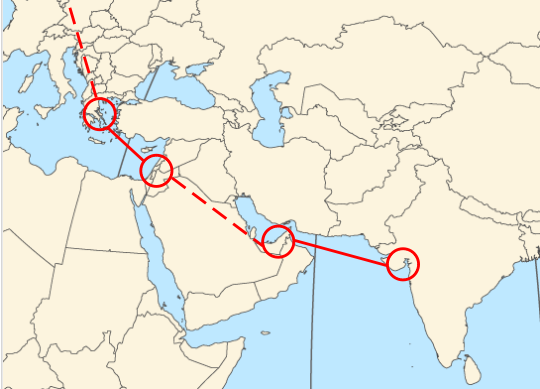

Understanding the region’s importance requires reconceptualizing based upon its maritime boundaries, rather than contemporary concepts of political geography. Indeed, historically speaking, the connection between the Middle East’s maritime littorals that builds a synthetic geopolitical region is obvious. The Mediterranean was the locus of a string of European and Middle Eastern imperial powers, from successive Persian empires to that of Alexander, and then Rome followed by Venice.

These imperial powers dominated the Mediterranean, as well as the Black Sea and Red Sea. Control of the former provided access to the Dnipro, Danube, and Don trade routes, and some links over the Caucasus to the Caspian. Control of the latter provided access to lucrative Indian and East Asian markets, linking Eurasia’s halves into an interconnected long-range commercial whole. The collapse of structured regional European trade with the Roman Empire’s implosion shifted the European center of gravity to the north, particularly when the Frankish kingdoms dominated the western half of the peninsula. However, the Mediterranean-Black Sea-Red Sea nexus remained crucial, first allowing Byzantium to survive as a rump imperial entity, then facilitating the rise of the Italian maritime city-states, and finally serving as the key to struggle between the Ottomans, Italians, and Habsburgs. The Mediterranean-Black Sea-Red Sea nexus retained this central role during the First World War, with the Ottoman-German alliance preventing the most natural resupply route between the Western Allies and the Russian Empire.

Indeed, the separation between “Europe” and the “Middle East” stems from this post-1919, and more specifically post-1923, regional order, particularly given Turkey’s role. The newly founded Turkish Republic ultimately acted as a neutral during the Second World War. This separated the Black Sea and Mediterranean, even if both maritime regions were contested. The European balance of power after 1949 enshrined this separation. Turkey was NATO’s key bulwark against Russian expansionism into the Mediterranean and Red Sea, compelling Moscow to work with a variety of regional actors to leapfrog this disruption with only limited efficacy despite high costs. Meanwhile, the military aspects of the Black Sea balance, especially along the Ukrainian Black Sea coastline, were principally relevant to continental European calculations proper, rather than Mediterranean ones, given the location of major Soviet ground and air combat formations and the character of the European balance.

The current situation should remind observers, and compel policymakers, to once again integrate Middle Eastern and European concerns into a broader strategic picture centering upon the Black Sea-Mediterranean-Red Sea maritime theater. Russia’s war against Ukraine is as much about this theater as it is about the Eastern European front-line. Control of Ukraine would allow Russia to subvert and isolate Romania and Bulgaria, having already prepared the groundwork for cooptation in Hungary, Slovakia, and Serbia, and thereby undermine Turkey’s already tenuous links to the Western camp. With these leverage points, Russia could act as a Mediterranean power for the first time in several generations, threatening NATO’s vulnerable southern European members Italy and Spain. The result is another key leverage point to unravel European security structures, alongside the axis of advance against Poland through Ukraine and Belarus.

This makes the Ukraine War, in many respects, a Middle Eastern war as much as European one.

A similar remark can be made of the war between Israel and Iran, which has exploded into the open since October 7th, 2023. Iranian ambition and ideological invective demand the Islamic Republic expand its domination of the Levant, building a land bridge to the Eastern Mediterranean. By destroying Israel as a political entity, Iran can then become a central player in the European-Mediterranean balance, particularly if it has an operational nuclear arsenal and maintains reasonable relationships with China and Russia. The Israel-Iran war thus has direct implications for the European balance of power, precisely because of the links between the Middle East’s maritime littorals.

Eurasia, once again, must be the lodestar of American policy and strategy. The US is not competing with powers in individual regions but competing with China for dominance of the Eurasian landmass. In this respect, the Middle East’s littoral realities also provide the region with a central role.

The Middle East and Europe together form a crucial backstop in the broader Eurasian economic and trade system, given the former’s energy reserves, the latter’s financial and technical capacity, and their combined trade chokepoints. By securing Europe and the Middle East – and more to the point, by securing the Middle East’s maritime littorals, which include the Black Sea – the United States can both neutralize a threat from Iran and, crucially, lock Russia out of western Eurasian competition.

This will make the choice between subjugation to China or rational partnership with the West, a West that includes Ukraine, quite clear to the Kremlin. If Moscow’s elites do not recognize this reality, their fate is to be integrated into Chinese political economy, which will also make China responsible for Russia’s economic sustainment in a situation of severe demographic decline and likely accelerating social unrest. Regardless of the choice made, then, the United States is placed in a more coherent strategic position.

Executing such a strategy requires a forward leaning military element in the Middle East as well. Iran has suffered several major strategic setbacks, most notably the loss of its Syrian proxy partner in late 2024. Russia may be able to maintain some access to Syria, but its relationship with the new regime will be both transactional and lack the same degree of positive leverage for Moscow as its relationship with Assad’s dictatorship. Iran, however, is extremely exposed, without Syria as strategic depth, while its proxy Hezbollah is vulnerable to direct Israeli pressure. The Trump administration is considering, it would appear, a major campaign against Iran’s Houthi proxy in Yemen, which would destroy another member of Iran’s outlying defensive belt. If coupled with a renewed Israeli war in Lebanon, and carefully signalled deterrence mechanisms against Iran, this could finally open the road for strikes on Iran itself, or trigger Tehran’s authentic limitation of aims.

The key to executing such a strategy, however, is to recognize the fundamental linkages between each Eurasian region and construct a framework that truly integrates elements of American power across Eurasia to the US’ long-term advantage. The maritime Middle East is key to this understanding. Indeed, the litmus test for US policy coherence or ineffectiveness is likely to be not precisely the Trump administration’s approach to China, at least not in the short term, but to Russian-European tension and the Middle East crisis.

Seth Cropsey is the president of Yorktown Institute. He served as a naval officer and as deputy Undersecretary of the Navy and is the author of Mayday and Seablindness.