- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- History

- Military

- US

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Revitalizing History

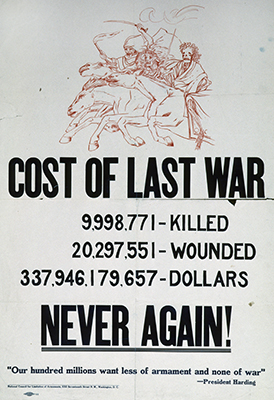

The calamitous withdrawal from Afghanistan not only marks the end of America’s longest war. It also represents the end of an era of intervention in the wide region stretching from the Mediterranean into Central Asia. The long announced “pivot to Asia,” the response to an increased threat perception concerning China, and the need to reposition U.S. forces to the Indo-Pacific, have come to imply a de-prioritization of the broad Middle East. Protestations to the contrary, this is a zero-sum game, especially given growing pressures on defense spending. Gone are the days of an American capacity to wage war in two major theaters simultaneously. The important story about the Afghanistan retreat is not the indisputably shameful way it was carried out, but the reality that the United States has to leave the region in order to engage elsewhere.

The two decades in Afghanistan began in October 2001 in the aftermath of the attacks of 9/11. But what followed did not only stay in Afghanistan. In 2003, the invasion of Iraq began, an extension of the Clinton administration's bombing campaign that had followed on the 1998 “Iraq Liberation Act” mandating regime change. That campaign continued through 2011, but Americans returned to Iraq a few years later as part of the war against ISIS. In that same year, as the Arab Spring spread across the region, the Obama administration participated in the bombing campaign in Libya. Finally, in 2015 U.S. military operations in Syria began, also as part of the war on ISIS. From Central Asia to the central Mediterranean region, from Kabul to Tripoli, the United States has been expending precious resources. The Trump administration was the first in decades to refrain from starting a new war.

Why did we plunge into these adventures? What was accomplished? Are we better off now than before?

Three factors overdetermined the interventionist policy decisions. First, the last decade of the twentieth century had witnessed the transformation of the East European Communist countries into western-style democracies. Against that backdrop, Washington policy makers could view the prospects for regime change in the Middle East with excessive optimism. The initial pursuit of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan quickly turned via mission creep into plans to democratize the country, as if Kandahar were Prague.

Second, the trauma of 9/11 focused American attention on Sunni Islamist terror, producing a predisposition to discount the malign activities of Iran, with bizarre results. For example, despite the obviousness of Iranian anti-Americanism, the American defeat of Saddam Hussein opened Iraq to Iranian influence in a way inconsistent with American interests. We have proceeded with an asymmetrical understanding of our adversaries.

Thirdly, the giddy globalization ethos of the 1990s prevented the foreign policy establishment from asking about the specificity of American national interest as distinct from some idealistic global good. The question as to how a particular policy benefitted the U.S. was not posed robustly enough. American efforts in fact sometimes end up helping our adversaries, as when Russia enhanced its military posture in Syria, or China takes advantage of mining opportunities in Afghanistan. Parts of the foreign policy establishment have displayed a remarkable naivete, a willingness to expend American resources without taking a hard enough look to determine who would benefit. It is telling that in the wake of these various campaigns, with their mixed results, no one in the military, diplomatic, or political leadership has ever been held accountable.

It would be foolish to claim that all these American efforts achieved nothing. Saddam Hussein’s dictatorial “republic of fear” is gone, which is an unqualified good, even if the Iraqi political process remains flawed, and the low rate of voter participation in the recent election bodes ill for the young democratic institutions. In addition, with its small force, the U.S. maintains strategic positions in Syria; while American power is insufficient to impose a political solution, neither can Assad control the whole country, nor can Russia establish a stable client state. In contrast to those ambiguous outcomes, Libya remains in the catastrophic throes of a civil war that is attracting foreign powers, including Russia, while the chaotic departure from Afghanistan squandered the real victories achieved by the U.S. military and its allies. America’s standing in the region is weaker today than it was two decades ago, despite the often heroic deeds of our soldiers.

The lessons to be drawn are too familiar and unfortunately too often unheeded: the need to test every policy in terms of its relation to the national interest, the importance of broad public support for any foreign intervention, and the willingness to use the full force necessary to achieve a victory. These two decades of war, with meager results and no accountability, have not served the country well.