- Education

- K-12

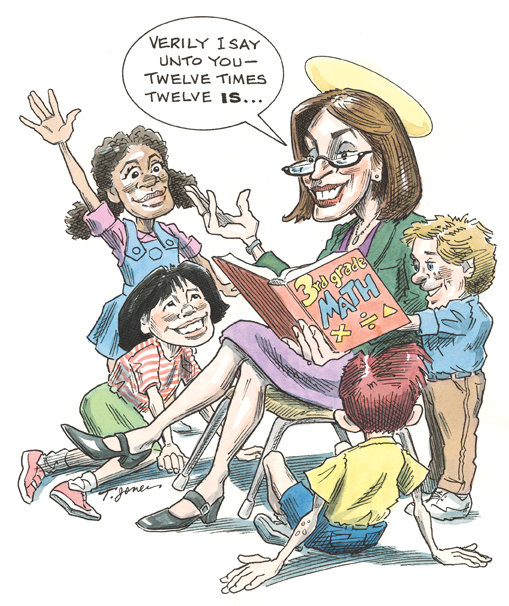

Teacher-bashing is a motif of the day, usually cloaked in some high-minded rhetoric that pretends to praise them. Say the bashers, “We need great teachers; great teachers can solve all our problems; great teachers can close the achievement gap; if you don’t have great teachers, you are doomed,” and so on. What they really mean, if you read between the lines, is that they think most of today’s teachers are no good: we have to start firing the stragglers, the ones whose kids don’t get high test scores. The theory is that, emulating Jack Welch at GE, we should fire the bottom 10 percent every year and that over time we will have a staff of “great” teachers because all the bums will be gone.

I recently attended a conference where a well-known scholar actually proposed that school systems function this way. Just keep firing the “weak” and replacing them with newbies. That way, the teaching force will get continually better.

The reasoning is partially founded on the belief that recent Ivy League graduates (believed to be the best and the brightest) will fill the ranks of the teaching corps and thus solve the problem of recruiting “great” teachers. I am still trying to understand the math. Teach for America brings in 5,000 or so teachers a year, yet there are 3 million teachers in America. I don’t believe that Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Brown, and Berkeley will ever supply enough teachers to fill the need. Nor am I persuaded that someone will definitely be a great teacher just because he or she graduated from a highly selective college. I know people who are utterly brilliant and highly educated, holding degrees from the best colleges, who were failures in the classroom. And I know superb teachers who graduated from state universities.

The quest for the mythical great teacher—the one we must stalk like some rare beast of unsurpassed beauty—is tinged with contempt for the large majority of teachers who did not go to Princeton or Swarthmore or Harvard. I habitually read news articles online about what is happening across the nation in education, and I frequently read the comments. When there is an article about teachers, it is often followed by a series of comments that express rage toward teachers. “She got what she deserved.” “These lazy teachers, they work only ten months a year, and they have the nerve to complain.” “No wonder our kids are failing when we have teachers like that!” “Why should they get a raise? They have an easy job.” On and on go the complaints. I try to figure out the source of all this anger toward teachers, and I just don’t get it.

Moreover, the news is captivated by hype and spin. It seems that many journalists won’t write about education unless they can find a miracle to write about. So they find a teacher or a school where kids who were completely indifferent to learning were suddenly transformed by the inspiration of one teacher or one school. A classroom full of sullen thugs turns into mathematical geniuses or poets. When people see this narrative again and again, they must wonder why not every teacher is performing similar miracles. After all, the proof is in the movies. And, as many of my illustrious peers often say, “If it can happen in one school, it can happen in all schools.”

As long as we expect schools to perform miracles, we will continue to be bitterly disappointed. Perhaps this phony expectation is what has created so much anger and frustration among the public. Surely they wonder why teachers can’t all be like Jaime Escalante of Stand and Deliver or any of a dozen other miracle workers.

I am also struck by the journalists who see a miracle where none exists. Geoffrey Canada’s school, as described by Paul Tough (Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America, Houghton Mifflin, 2008), is one such case. It actually is a story of Canada abandoning the kids who started at his charter school because they couldn’t get the scores he wanted. So out they went. No miracle there!

Another miracle was reported in the New York Times around Inauguration Day. Three researchers administered parts of the Graduate Record Exam before and after the presidential election to a group of African-American adults. Several months before the election, there was the usual achievement gap between the races, but after Barack Obama’s nomination, and again after his election, the gap closed. I had an extended e-mail exchange with a friend who wanted to believe that this report was valid. I finally responded: “Yes, yes, we can stop worrying about the achievement gap. Now that Obama has been elected, everyone will read at grade level, none below. I can’t wait to see the results of the next state tests. We can all stop worrying now. The kids who couldn‚t read last year will now be proficient.”

Miracle cures in education, much like the elusive great teacher, emphasize the mystery of why so much gullibility exists. People certainly don’t anticipate miracles in any other part of their lives, but the schools can’t seem to break free of these expectations. When will students learn to the highest standards? Miracles on offer include when

1. All teachers are great teachers;

2. Every school has a brilliant leader as principal;

3. Every superintendent has an MBA;

4. Every school is run by entrepreneurs;

5. Every school is organized around a theme;

6. Every school is small;

7. All schools are charters.

I know that multiple-choice questions are supposed to offer only four answers. In this case, I could have added ten or twenty more.