- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

Entrepreneurship has played a decisive role in American identity and aspirations, but it is a role marked both by uncertainty and longing. Ronald Reagan, who spoke fondly of a "nation of entrepreneurs," referred to entrepreneurs as "forgotten heroes." He remarked that "we rarely hear about them. But look into the heart of America, and you’ll see them. They’re the owners of that store down the street . . . the brave people everywhere who produce our goods, feed a hungry world, and invest in the future to build a better America."

We do hear a lot about them today, at least about those who have created the enterprises that have filled the world with computing and communications devices and seem to be literally minting money in the process. Economic prognosticators see entrepreneurship as the main—no, perhaps the sole—pathway to a prosperous future. One labor expert quoted by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman asserts that successful job candidates these days need to be "inventors and solution-finders who are relentlessly entrepreneurial." The days of large labor forces with places for every good steady worker are vanishing fast. As many news outlets have noted, one recent canary in the mine is the valuation of a 55-employee company (Whatsapp) at nineteen billion dollars. It does not take many salaried jobs to run many of our emerging companies, a reality that future workers may need to adapt to by becoming entrepreneurs themselves.

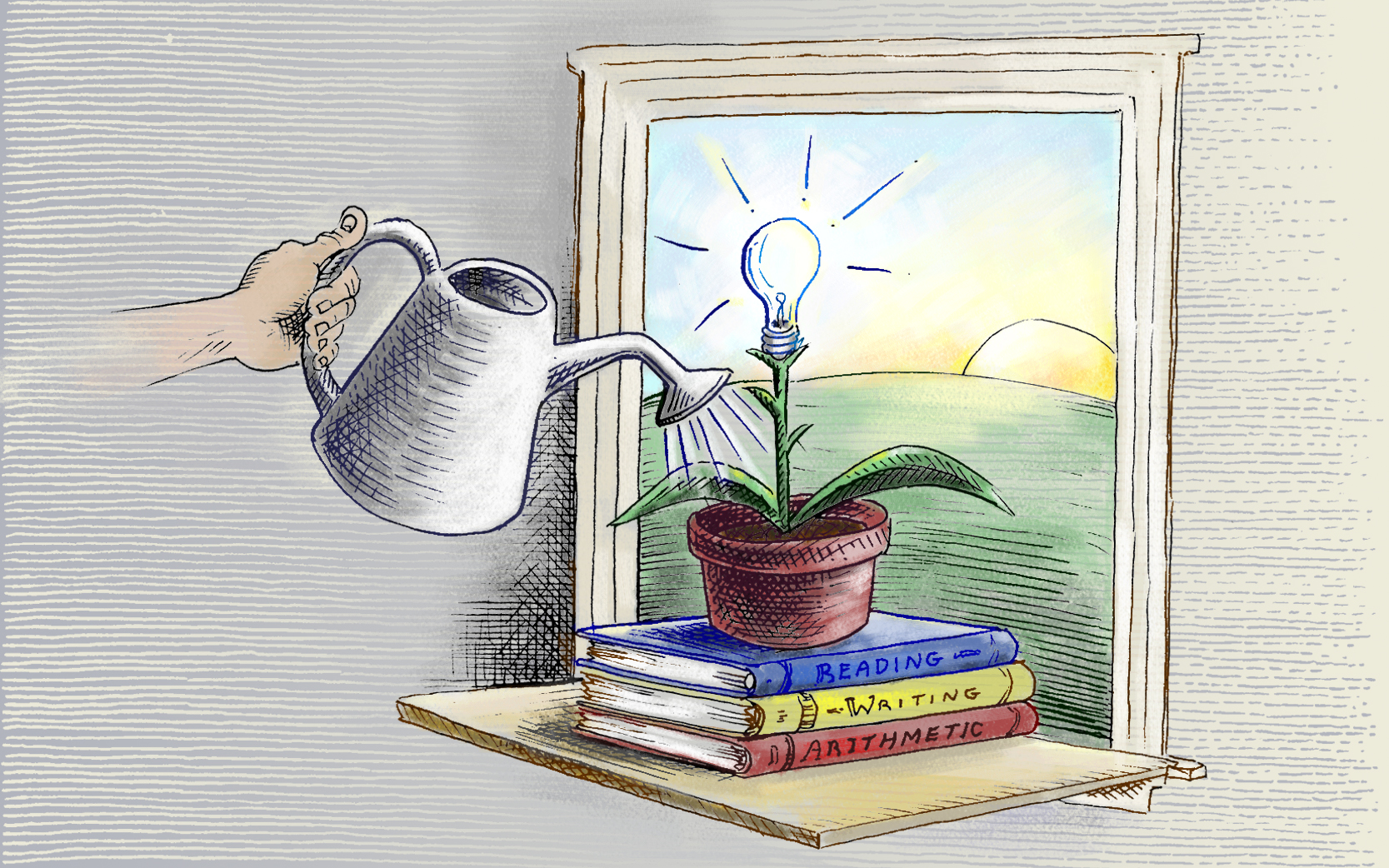

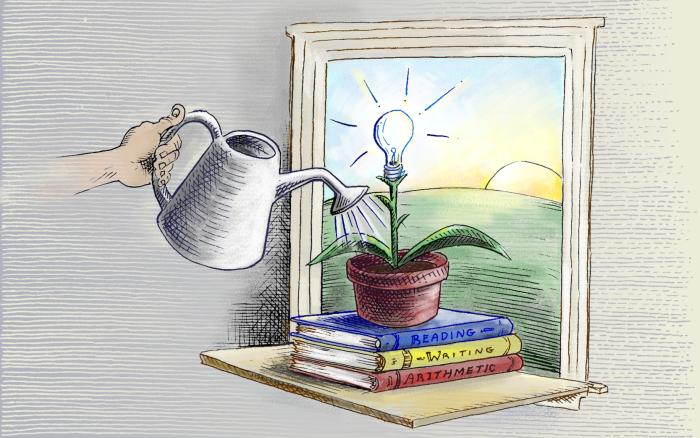

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Yet the large majority of the U.S. working population is not entrepreneurial. Even the most optimistic accounts of present-day entrepreneurial activity show only a relatively small minority of the U.S population pursuing venture opportunities. The Global Economic Monitor has estimated the figure as a mere 11% of the population, and the Kauffman Foundation has reported that in 2008 only 2% of U.S. jobs were in start-up companies, actually down from 3% in 2005. Nor, despite the value that American mythology places on free enterprise, does the U.S. stand out as a special haven for budding entrepreneurs. Between 2007 and 2009, according to OECD (the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), the start-up rate of new companies in the United States was lower than in many other countries, including Sweden, Israel, Romania, Spain, Mexico, Italy, Estonia, Finland, New Zealand, Austria, and Brazil.

This hardly accords with popular impressions that have been fashioned by stories of larger-than-life American inventors like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates or by legendary hot-spots of innovation such as Silicon Valley. Indeed, most workers are turning away from entrepreneurship as a vocational choice: recently a Wall Street Journal piece entitled "Risk-Averse Culture Infects U.S. Workers, Entrepreneurs" reported that the majority of U.S. workers are shunning entrepreneurial risks. An economist is quoted as saying "The pessimistic view is that we've lost our mojo."

What is happening to the entrepreneurial spirit in the nation at large? Is it waning, except among a fervent few? If so, are we failing to cultivate it in the places where Americans are raised and educated, most notably our homes, communities, and schools? The Young Entrepreneurs Project, a joint Tufts/Stanford initiative of which I am a co-director, is addressing these questions through surveys and interviews with college students who have expressed an interest in entrepreneurship. We are looking carefully at what happens to personal qualities essential for successful entrepreneurship during the formative years of youth and early adulthood.

What are these qualities? This is a question that many observers have opinions about, and there is no lack of lists: a simple Google search for "characteristics of entrepreneurs" yields over 15 million hits, all identifying 7, 8, 10, 25 (and so on) personal qualities required for a successful career as an entrepreneur. There is significant overlap among these numerous lists. Risk-taking is prominent, along with discipline, perseverance, creativity, leadership, motivation, sociability, optimism, and curiosity. The great majority of these lists have been generated through intuition; but one recent empirical exception is a study of 5,000 business innovators, described in the book The Innovator's DNA by Hal Gregersen, Jeff Dyer, and Clayton Christensen, that found common mental habits such as questioning, experimenting, observing, connecting ideas, and networking are critical to the entrepreneurial spirit.

All these personal and cognitive qualities are available to anyone. Although it is true that individuals differ from one another in certain temperamental predispositions, there is absolutely no evidence that there are genes for any of the qualities that enable successful entrepreneurship. These qualities must be nurtured or acquired through educational experience. If large sectors of today's population do not demonstrate such qualities, something has not been made available to them in their educational experience.

Can schools fill this gap? At present, it is hard to say, because so few of our schools are even trying to address entrepreneurship and the cognitive or personal skills that make it possible. At the K-12 level, the focus in recent years has been increasingly on basic (and usually remedial) literacy and numeracy skills that may help students find jobs as paid workers (a good thing) but that have little to do with the interests and mental habits that drive entrepreneurship. Many of the subjects that could interest potential entrepreneurs—subjects such as finance, economics, media studies, technology, art, music, and theater—have been dropped to make room for instruction in basic academic skills with little obvious immediate application other than test-taking. When in college, students are offered a rich menu of liberal arts courses, but without much guidance about how to turn what they have learned into a productive enterprise. For many students coming from today's high schools or colleges, the most they can aspire to is salaried work after graduation, if they are lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time if and when such work become available.

Our higher educational system has not been totally oblivious to such shortcomings: there have been attempts in recent years to offer college students direct instruction in entrepreneurship. In most cases, such attempts have been heavy on presentations of theory and light on cultivating the personal and cognitive capacities that drive successful entrepreneurship.

A case from our data set illustrates this common pattern. Charles (not his real name) took a concentration in entrepreneurship at a leading American public university. We first spoke with Charles while he was enrolled in this program. He had high hopes for an entrepreneurial career, describing himself as "intelligent," "ambitious," "good with people," and wanting "to build my own business . . . to be successful." He also had strong interests in topics with enterprise potential, such as technology and agriculture. Charles was enjoying the entrepreneurship courses that the university was offering him, although he had certain intimations of their limitations: he said that he had always learned best "by doing," but the courses consisted mostly of reading books, online learning, and visits to start-up companies accompanied by the instructor's analysis of how the companies represented various business models. The visits were part of an "entrepreneurship lab" that Charles particularly enjoyed, but from his description, the experience sounded more like observing than participating in the companies' business activities.

Two years later, after graduating from the university program, Charles expressed a very different sense of his goals and prospects. No longer aspiring to found a business, Charles has been working at a 50-hour-per-week-job and trying "to make myself I guess a more valuable employee so that I can take that with me to other companies and hopefully get paid more in the long run." Other than this, he had "really no set goals." This twenty-something complained that "my life isn't too exciting," noting that he gets "bored easily" and often will "start a project and then I'll lose interest and move on to like the next thing." He spoke of his entrepreneurial desires in the past tense ("I wanted to be my own boss, I guess").

Most notably, he regretted his choice of college major: "If I were to do it again, I probably wouldn't choose entrepreneurship as my major. Because I think that kind of limits you when you get out to find a job. . . . I guess the hard thing is . . . whether you can really learn entrepreneurship, or whether it's just something—I mean, can it be taught in a classroom environment, or is it something you kind of pick up along the way? I probably wouldn't do it again. It's interesting, I enjoyed it. It's pretty easy . . . but I wouldn't do it again, probably." Many of Charles' classmates feel the same way.

Whatever its efforts and intentions, our educational system has failed Charles and others like him. Rather than fostering capacities that could help them turn their entrepreneurial interests into thriving careers, these students' educational experiences have offered them little more than inert conceptual views of what start-up companies look like from an observer's perspective. As a result, their ambitions atrophy. So too does their optimism, one of the key qualities that enables successful entrepreneurship. Charles may be further away from an entrepreneurial career at the end of his college years than when he began.

No matter what the economic future brings, entrepreneurship is not for everyone. There always will be a social need for good workers in traditional salaried occupations of many kinds, and such workers will find meaning, pride, and sustenance in such work. But global technology is opening new pathways toward entrepreneurial careers and shifting the workforce balance in their favor. Our schools must do more than simply sort out those who already have the initiative and staying power to find and follow such pathways. At the pre-college level, our schools should make room for the range of subject matter that inspires student interest in the world beyond the classroom and cultivates the broader character strengths and mental habits that lead to success. In college, students should be offered opportunities to gain active experience in practical endeavors that build their skills and confidence rather than discourage their aspirations. Education, like all else, serves us best when it not only adapts to the times but grows along with them.