- Contemporary

- Campaigns & Elections

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

Polls indicate that Rudy Giuliani—the thrice-married, twice-divorced, pro-choice, civil-union-supporting former New York City mayor—has become the front-runner for the Republican presidential nomination. In key states, Giuliani is polling even with or ahead of likely Democratic challengers. Meanwhile, commentators, particularly on the left, are forecasting with increasing confidence the coming of a conservative crack-up.

So which is it? Is conservatism, as led by a tax-cutting, crime-fighting, socially liberal big-city blue-state former mayor, about to remake itself by reclaiming the center of American politics? Or is it about to collapse from the combined force of its internal contradictions, the legacy of congressional Republicans’ profligacy, and the errors, real and imagined, of the Bush administration?

In assessing conservatism’s prospects, it is important to recognize that President Bush has been no ordinary conservative. Therefore it would be a mistake—no less for conservatism’s opponents than for conservatives themselves—to assume that the fate of U.S. conservatism stands or falls with that of the Bush administration.

Bush is a hybrid conservative. Although he favors, and has brought about, lower taxes, his platform was not against the welfare state; indeed he has enacted education and prescription drug bills that have expanded it. Although he won and has kept the confidence of social conservatives, he has not spoken out against abortion, has liberalized Clinton-era restrictions on embryonic stem cell research, and has spent as little political capital as possible supporting a constitutional amendment restricting marriage to a man and a woman.

Although he has pushed the outside of the legal envelope when it comes to the detention, interrogation, and prosecution of enemy combatants, he sought authorization from Congress for the war to remove Saddam Hussein and then from the United Nations. In doing so, Bush respected legal forms in the run-up to hostilities to an extent rivaled since the end of World War II only by his father, for the first war against Iraq in 1991.

In 2000, Bush presented himself to the nation as a compassionate conservative, combining a typically progressive emphasis on caring for the least well-off and a conservative confidence in private-sector solutions. He made clear in his first campaign that neither his compassion nor his conception of the U.S. national interest extended to nation building. Yet he has staked his post–September 11 presidency on a grand task—promoting democracy in Iraq—that shows a confidence in government’s ability to improve the world that terrifies most progressives.

As distinctive as the mix that Bush presents is, all modern conservatives are, in a sense, hybrid conservatives. That’s because modern conservatism itself is the offspring of a family of competing opinions and principles.

Modern conservatism derives above all from Edmund Burke, the great eighteenth-century Anglo-Irish orator and statesman. Burke was a lover of liberty and tradition who saw a great threat to liberty in the tradition-overthrowing forces unleashed by the French Revolution. He was solicitous of established ways but acutely aware that preserving liberty required “prudent innovation” in response to the constantly changing circumstances of political life.

Yet since individual liberty can never be entirely divorced from the French revolutionaries’ ambition to remake society in the name of equal freedom for all, modern conservatism contains a built-in instability.

There is no settled recipe, no fixed proportions, for determining the prudent innovations that balance liberty and tradition. For example, reasonable people who agree on the importance of both may differ on whether the benefits that come to the poor and vulnerable from government efforts to cooperate with faith-based charities outweigh the dangers of mixing church and state.

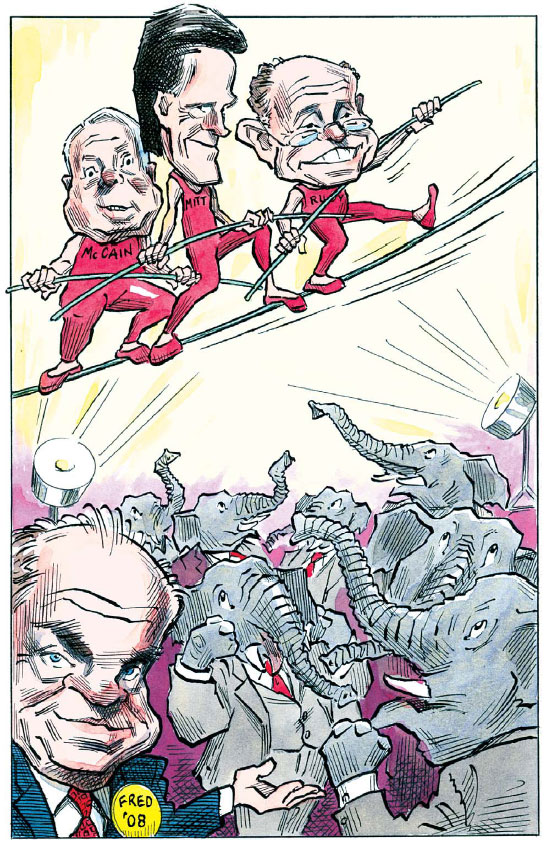

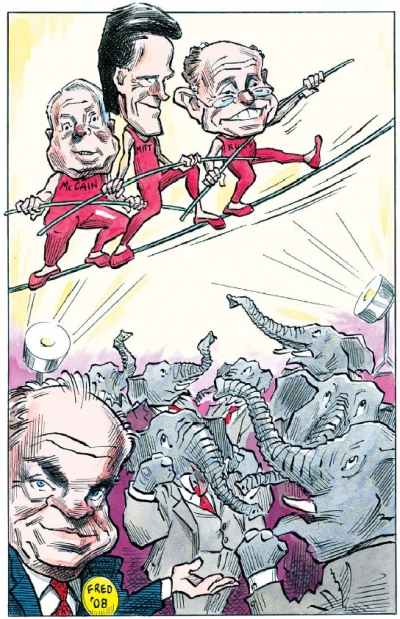

All three leading candidates for the Republican nomination embody a mix of conservative elements different from those of Bush and of each other. All three have evidently rejected Karl Rove’s maximize-the-base strategy in favor of a formula that will allow them to appeal to moderates while keeping the confidence of the base. And all three face a delicate balancing act.

Former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney puts his social conservative credentials first, opposing abortion and embryonic stem cell research and supporting a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. At the same time, he is a successful businessman who has learned to woo and work with Democrats by serving as governor of the bluest of blue states.

Senator John McCain of Arizona is the foreign policy hawk, which is in keeping with the importance the conservative mind attaches to order, as well as its appreciation of the diversity of human types, including the types that present a deadly menace to one’s nation. During his 24 years in Congress, McCain has been consistently antiabortion. But he has alienated many Republicans with the campaign-finance-reform law that bears his name because it puts its trust in government regulation rather than in individuals and the marketplace of ideas.

Rudy Giuliani is running as a problem solver whose mind is concentrated on the urgent requirements of homeland security. He prefers market solutions in education and health care, but he prudently understands that the solution to the problems of government is not always less government but sometimes—as in the case of protecting the nation from terrorists—better government. And, in insisting on his commitment to appoint judges in the mold of Samuel Alito and John Roberts, he may well manage to quell social conservatives’ anxieties about his socially liberal opinions.

At this early juncture, one prediction, suggested by the classic liberal tradition, seems reasonable: the competition and conflict developing among the leading conservative candidates should prove invigorating, not only for conservatism in America but for the nation as a whole.