- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

HAVANA—As the small jet lands at Havana’s José Martí airport, I half expect the pilot to get on the intercom and announce, “Welcome to Cuba. Please set your watches back 40 years.”

Cuba exists in a time warp. Traveling around the island, one gets the impression that little has changed since the revolution, that the country has been in a state of suspended animation since Castro took power in 1959. Havana is a poor shadow of what it must have been 70 or 100 years ago, with most of its glorious, old colonial buildings in an advanced state of decay. Besides some renovation in old Havana (a World Heritage site), little recent construction is evident in the city, aside from the occasional dreary Soviet-style concrete office buildings and apartment complexes (many of which were, indeed, built to house Soviet advisers and workers).

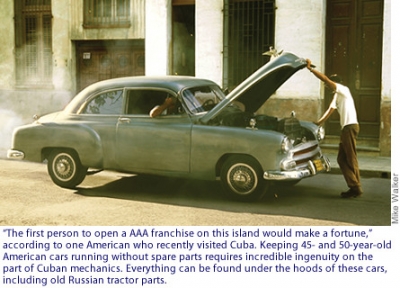

One does not need a PhD in economics to realize that Castro’s planned socialist utopia is an impoverished, dysfunctional mess. The fact that most of the cars on the road are from the 1950s is one indicator that things are amiss. (The island is a haven for vintage American cars from the 1940s and 1950s, most of which have been kept running through the ingenuity of Cuban mechanics and jury-rigged parts. There must be more old Edsels and DeSotos here than anywhere else on the planet.)

Before the Soviet Union collapsed, it was giving a reported $6 billion a year in aid, subsidies, and credits to Cuba. It is estimated that the Soviets spent roughly 10 times the amount of the Marshall Plan in their 30-year subsidy of the island. So where did all the money go? It is certainly not in evidence on the streets of Havana—or in Camagüey, Cienfuegos, or Trinidad, for that matter.

As one of the world’s last remaining communist states, Cuba has become something of a living museum to the failures of twentieth-century communism. For the Western visitor, it is surreal to see billboards extolling the revolution with anachronistic exhortations such as ¡Viva Fidel y la Revolución Socialista! (Long live Fidel and the socialist revolution!).

On the outskirts of Havana, I watch a group of Western tourists rush out of their air-conditioned tour bus to take photos in front of a billboard featuring a dramatic montage of Che Guevara portraits and the slogan Che Vive en el Corazón del Pueblo (Che lives in the heart of the people). As the Westerners snap their photos, 20 or so Cubans stand across the street in the stifling heat looking tired and beaten down as they endure a long wait for a local bus that might never arrive. (Because the government is too cash-strapped to maintain a reliable public transportation system, Havana’s buses are notoriously unpredictable. And when they do show up, they are insanely hot and crowded. According to a local joke, no man leaves a Havana bus with his wallet and no woman leaves with her virginity.) For the Westerners, the Che billboard may be kitsch, but for the Cubans, it is simply the omnipresent symbol of their failed revolution.

Another slogan seen throughout the island is En Cada Barrio, Revolución (In every neighborhood, revolution). To keep the revolution alive, every neighborhood has an office of the Committee to Defend the Revolution, a communist version of a neighborhood watch program in which neighbors keep a vigilant eye out for signs of counter-revolutionary activity (such as contact with foreigners).

This is a country in which criticizing the government can land one in jail (indeed, 75 political dissidents were summarily tried and imprisoned last spring), and yet it doesn’t take long to come across ordinary Cubans willing to complain to a foreign visitor about their plight. Walking along Havana’s Malecón, the charming seaside promenade on the edge of the city where throngs of Cubans gather every night, I encounter numerous Cubans who describe how hard it is to live on their state ration books and monthly salaries of $8 or $10. (Even Cuban surgeons only earn the peso equivalent of roughly $20 a month.) No es fácil (It is not easy) is a common refrain throughout the island. “It is impossible! It is impossible! Life here is impossible!” a young Cuban woman exclaims, becoming increasingly emotional as she describes the hardships of daily life.

According to a Cuban joke, the three successes of the Cuban revolution are health, education, and athletics. The three failures? Breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Scarcity is simply a fact of life. Cuba has twice as many doctors per capita as the United States and infant mortality rates on par with the United States, yet basic medicines (such as aspirin) are frequently unavailable. Likewise, Cuba has one of the highest literacy rates in the hemisphere, and yet its economy cannot provide a living wage to most of its people.

Following the collapse of his Soviet benefactor, Castro reluctantly instituted a series of reforms to keep the island from complete economic meltdown. The reforms were, in effect, begrudging concessions to capitalism. In 1994 the possession of U.S. dollars was decriminalized. Cuba now has an odd dual economy in which some stores accept only pesos and others accept only dollars. It is quite easy to distinguish the peso stores from the dollar stores: The shelves of the peso stores are virtually empty, while the most desirable goods (such as televisions, stereos, refrigerators, and fans) are generally available only in the dollar stores. (Of course, all stores are run by the government, which makes a hefty profit from sales at the dollar stores.)

The problem, of course, is that Cubans are paid in non-convertible pesos. Thus a huge economic chasm is growing between those Cubans who possess dollars and those who do not. For those Cubans not fortunate enough to receive gifts of dollars from relatives living abroad (mostly in the United States), the best way to obtain dollars is through contact with foreigners, most commonly by working in the tourist industry. Only a small percentage of the population is employed in tourism, but those who are lead significantly better lives. Thus it is not uncommon to hear of doctors and engineers working in hotels and driving cabs. A taxi driver I met in Playa Girón (near the Bay of Pigs) had quit his teaching job because he could make significantly more money driving tourists around. Prostitution, which Castro attempted to eradicate in the aftermath of the revolution, is now back with a vengeance.

¡Turismo o Muerte!

After decades of largely shunning the outside world, the Cuban government is now staking its economic future on tourism. It has few other options. The country has very little industry, given that it had largely relied on the export of sugar and other raw materials until the demise of the Soviet bloc. The collapse of sugar prices has devastated Cuban production of sugar, which had historically been the country’s single most important export. At the time of the revolution, Cuba was the world’s leading sugar producer, but many of its mills are now shuttered.

In its quest to lure tourists to the island, the government has invested millions to convert Cuba’s prime beaches and small coastal islands into lush tourist resorts reserved exclusively for foreigners. Only Cubans holding special papers indicating that they are employed at the resorts have access to them. The system—dubbed “tourism apartheid” by its critics—has, not surprisingly, caused a great deal of resentment among ordinary Cubans.

The recent decision by the Bush administration to further restrict the number of Americans who can visit Cuba cannot have been happy news for Castro’s government, which has much riding on a large increase in tourism.

Fidelismo

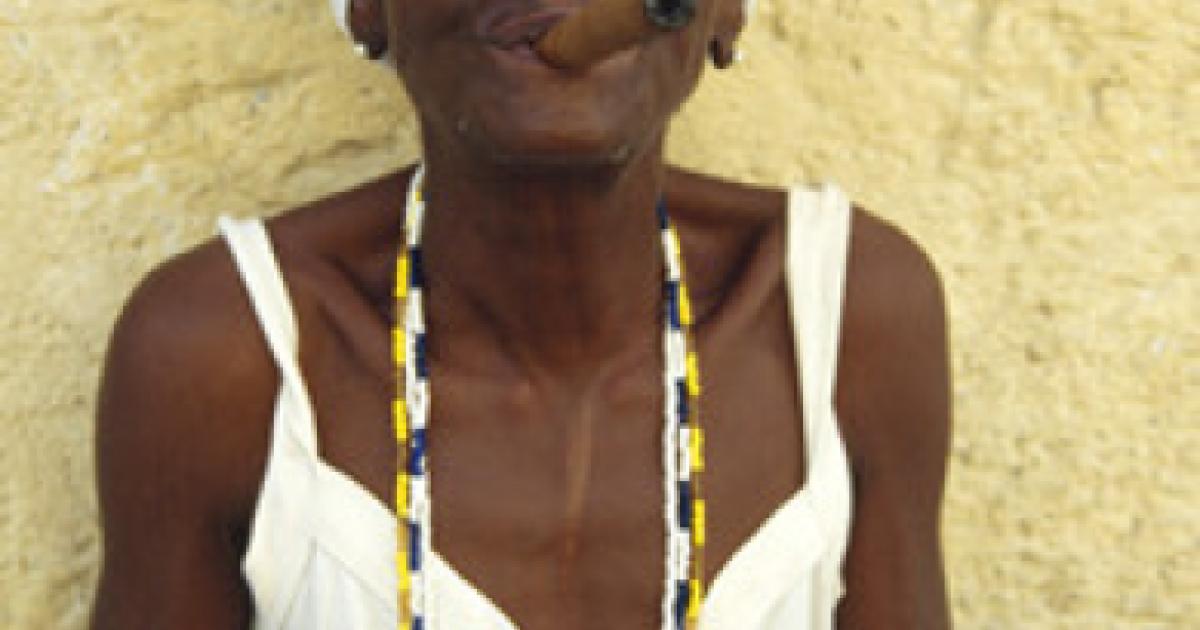

Near Viñales a tobacco farmer shows me his large tobacco shed, which is full floor to ceiling with tobacco leaves. Tobacco exports are extremely profitable for the Cuban government, but the crop provides only a meager living for those who grow it. The farmer must sell his entire crop to the Cuban government and will be paid a mere $35. I dare not ask him if he is aware that individual Cuban cigars sell for $20 and more in Mexico and Canada. (Farmers can now sell some fruit, vegetables, lamb, and pork at private farmstands to supplement their incomes. Other items cannot be sold privately; for instance, the unauthorized sale of a cow can land one in jail. Beef is a rare luxury in Cuba.)

A visit to a cigar factory offered an interesting glimpse into how the Cuban economy works. In each section of the factory, workers covertly offered our group individual cigars for $1 a piece. Every time the factory manager giving the tour turned his back, workers would flash contraband Cohibas or Romeo y Julietas hidden in their pockets, waistbands, or on their rolling tables. I was initially hesitant to buy the cigars for fear of getting individuals in trouble, but the workers were so brazen about it that it seemed clear that management was somehow in on the scam. By the end of the tour, my pockets were bulging with cigars—and I declined the opportunity to buy more from the official factory (i.e., government) store. I suspect that the workers at the factory make more by selling cigars “off the books” to foreign tour groups than they receive in government salary.

Witnessing all the unnecessary hardships that the long-suffering Cuban people endure, one wonders how long communism can survive in Cuba. Sitting in the plush outdoor garden of one of Havana’s paladars—the small private restaurants that the Cuban government tightly regulates—a Cuban woman tells me that “Fidel Castro is the richest man in the world. He owns 11 million people.” Her companion interjects, “Nothing can change until the old man dies. Nothing.”

Thus the 11 million people wait, resigned to their fate, to see if the “biological solution” (i.e., Castro’s eventual death) will improve their lives.