- Energy & Environment

- Science & Technology

- History

This past September, the U.S. Air Force introduced a cache of 20 new B61-12 nuclear bombs to the Luftwaffe’s Büchel Air Base in western Germany. The upgrade, part of the NATO program on nuclear “sharing,” replaced a higher-yield version of the venerable B61 with a less destructive weapon, but it nonetheless sparked protest by opposition parties in Germany. “The Bundestag decided in 2009, expressing the will of most Germans, that the U.S. should withdraw its nuclear weapons from Germany,” wrote one. “But German Chancellor Angela Merkel did nothing.”

Indeed she did not. Objections also came from the far right as well as the left. Willy Wimmer, a member of the Bundestag for more than 30 years and once defense spokesman for Merkel’s own Christian Democratic Union party, but also noted for his anti-American and pro-Russian views, warned that the warheads gave “new attack options against Russia” and constituted “a conscious provocation of our Russian neighbors.”

Why, at a time when Germans are paying painfully high energy bills to rid themselves of civilian nuclear power plants, would Merkel make such a controversial move? Not only did she approve the new B61-12 deployment, but her government has also announced that it will retain the Tornado fighter jet—also based at Büchel, where it routinely practices missions with dummy B61s—in its inventories until at least 2024.

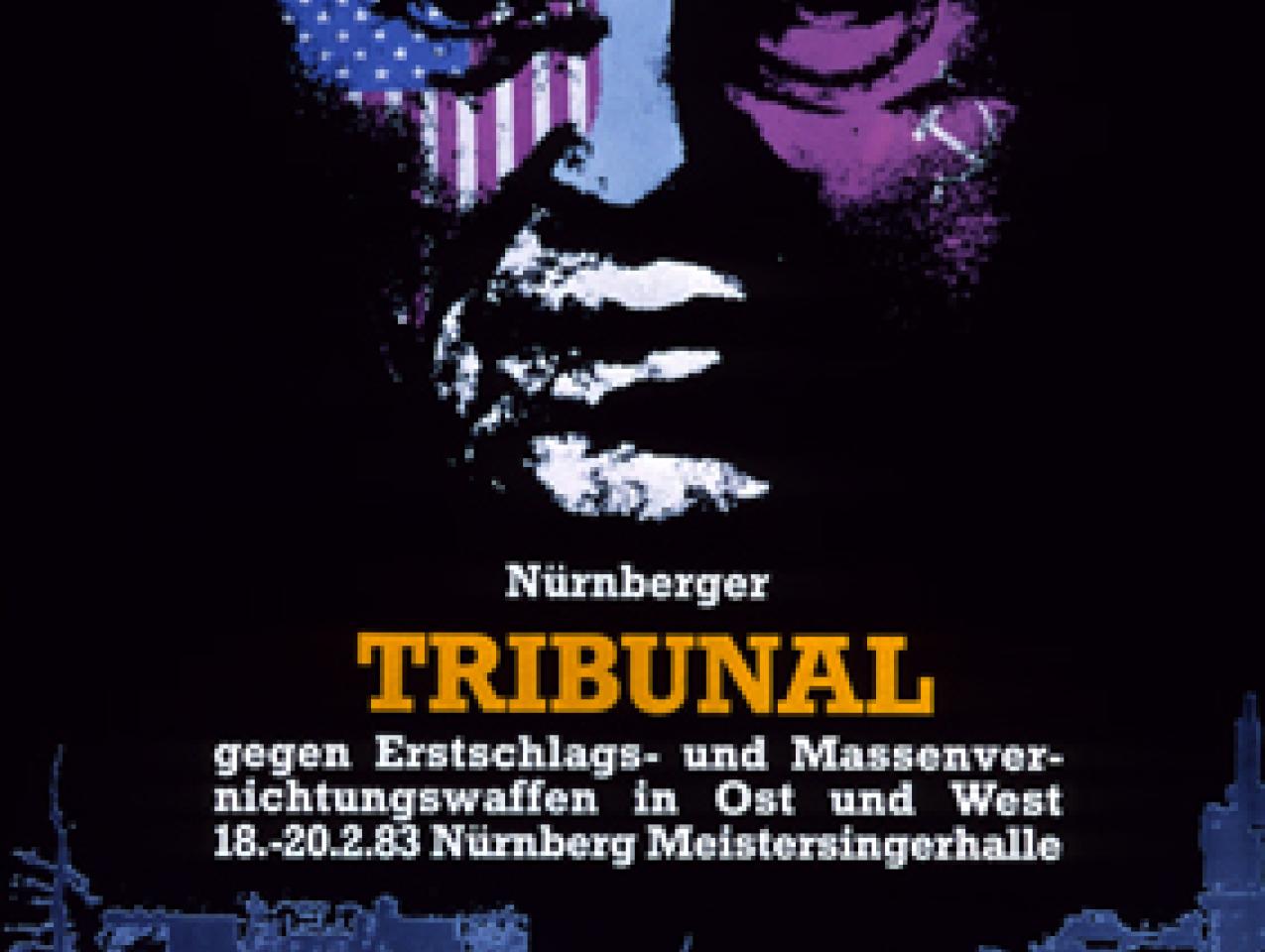

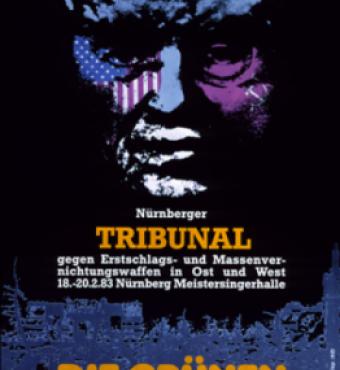

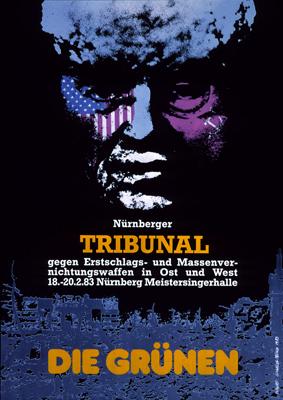

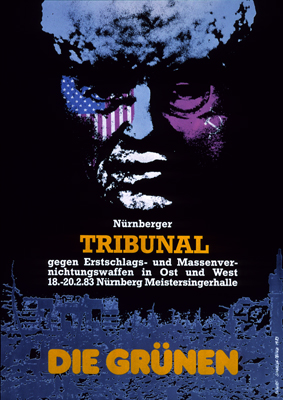

The no-nukes movement in Germany has a deep and long history. Beyond the broader make-war-no-more ethos that stemmed from Germany’s guilt after World War II, the Reagan Administration’s decision to deploy Pershing II missiles in Germany in the 1980s provided a focus for nuclear activists; the subsequent signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty removed the irritant along with the Pershings, but the movement endured. In the wake of the Chernobyl meltdown and the Fukushima disaster in Japan, it found its new target in Germany’s nuclear power plants. That campaign proved a success—though the decision to substitute unreliable and immature renewable energy sources is playing havoc with the German energy grid and the economy.

But the anti-nuclear impulse must also be seen in light of the powerful American security guarantees, and the deployment of substantial U.S. forces, to Germany throughout decades of Cold War. Safe under an American deterrent umbrella, Germans were free to posture without direct or immediate consequences. But as Barack Obama folds the U.S. umbrella, it raises incentives for Germans to rethink the question.

The fact is that Chancellor Merkel and centrist Germans have every reason to feel the need for new military and policy options to counter Vladimir Putin’s aggressive moves in Eastern Europe. The continuing Ukraine crisis, in particular, has begun to shake Germany out of its post-Cold War, post-modern dream. Another, ironic measure of how Germany is changing in the direction of geopolitical “normalcy”—that is, a nation whose fundamental concerns are for its security—is the angry response to Merkel’s refugee policies. Merkel’s personal confusion is representative of the country’s contradictions and self-doubts.

Nevertheless, Merkel is clearly striving to articulate a leadership role for Germany, with strong encouragement on the part of the Obama Administration. The Greek debt crisis naturally depended upon German willingness to finance any resolution and, despite a lot of grumbling and posturing, Merkel’s government has done enough to prevent the worst from happening. The mass-circulation weekly Bild went so far as to photoshop a cover of Merkel with a Pickelhaube. She was not quite the kind of “Iron Chancellor” that magazine wished for, but to the degree that there was any European leadership during the Greek melodrama, it came from Berlin. Josef Joffe’s two-cheers praise—“[She] knows she does not want to have a dead body on her hands—not in Europe, not in her Europe”—was accurate.

What might a German return to geopolitical normalcy look like? In one sense, a unified Germany is not normal; for most of the modern era, Germany was divided into lesser kingdoms, principalities, and “electorates” of the Holy Roman Empire. Its strategic orientation was as much eastward as westward and, when viewed from Berlin—that is, the capital of Prussia—more eastward. Indeed, the Cold War division of east and west might be said to be more in line with German historical experience than either unification under Bismark or George H.W. Bush.

In this light, the pattern of German behavior in the post-Cold War period may be more coherent than it otherwise appears. Notably, Germany has distanced itself from American and European interventions in the Arab world—in Iraq in 2003, when Gerhard Shroeder proudly announced he would not “click his heels” in response to Bush Administration entreaties; in Libya, when Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle laid out the Merkel coalition’s refusal to participate in NATO actions to remove Muammar Gaddafi, despite his insistence that “he must go;” and now in Syria, where Merkel has said she is willing to negotiate the fate of the Assad regime even as the refugee crisis roils Germany. In response to a direct request from the French in the wake of the Paris attacks to join the fight against ISIS, Merkel has deployed aircraft to help protect French forces in the region, but not participate in strikes on ISIS. By contrast, Merkel’s willingness to bear the burden of the Greek debt crisis and to shepherd the various Minsk agreements that have punctuated the Ukraine war would seem to mark a kind of new “Ostpolitik,” based upon a supposed special relationship with Russia and an underlying eastern-looking strategic orientation. Germany’s participation in Afghanistan might prove to be the exception to the new rule, a valedictory nod to the west and to Washington for the Cold War past.

Sustaining the strategic independence of a unified Germany will not be easy. The plains of north-central Europe are notoriously indefensible and have been the central battleground of the world’s great powers for centuries. Unification under Bismark arguably made things worse; Kaiser Wilhelm and Adolf Hitler were megalomaniacs, but their drive to dominate was in part a response to fundamental insecurities. In the end, unified Germany could not remain, as Bismark wished, a “satisfied power.”

The fissiparous trends of 21st-century politics and power seem likely to expose Germany to similarly cold winds. It is debatable whether Merkel-style leadership, which rests almost entirely on diplomacy and wealth, will provide the kind of security that Germany has taken for granted as a ward of the United States. If she cannot check Putin in Ukraine—and, thanks to his bold gambit in Syria, there will be mounting pressure to accommodate Russia in Eastern Europe—others in the region, especially Poland, will not want to follow where Berlin leads. Moreover, Germans have never been able to take a global view of the balance of power. The contrast with other European great powers, particularly Britain, but also Bourbon France, Habsburg Spain, and even Tsarist Russia, is marked. Even today, Western European countries have a residual impulse to try to shape the situation in the Middle East; Germany does not. To truly lead Europe, Berlin will have to export security to the west as well as to the east. And as China muscles its way toward a global role, Germany’s narrower strategic horizons will prove a limiting factor.

Further, Germany’s lack of conventional military power will be crippling to its ambitions to lead. During the Cold War, the Bundeswehr became a force to be respected. German tanks, German aircraft, German submarines were all top-notch. Its officer corps retained—and still retains—a tradition of professionalism despite a creeping politicization, especially in years of Social Democratic rule. The German military might have become more “normal” had the country been more serious about its commitment to Afghanistan. That seems not to have happened. Last February, the Germans sent the 900-man Panzergrenadier Battalion 371 to participate in high-profile NATO exercises in Norway. This allegedly elite unit, part of the NATO Rapid Reaction Force, had to borrow 14,371 pieces of gear from a total of 56 other Bundeswehr units, yet still was short on equipment. To simulate MG3 machine guns, the Germans painted broomsticks black.

Which returns us to the original question: Is Germany’s antipathy to nuclear armaments a forever-and-always commitment? Allowing the U.S. Air Force to substitute one model of a B61 bomb for another hardly constitutes a new arms race in central Europe (although Russia’s love affair with shorter-range missiles has already moved them into a leading position). Despite the popularity of the anti-nuclear movement, German leaders have quietly but consistently accepted the need for a theater-level deterrent, one that gave “attack options against Russia,” most of all when the conventional military balance was uncertain.

Germans have thus far been able to trust in the United States to provide that deterrent. Others in Europe have not: thus France’s force de frappe. And the Obama Administration remains committed to drawing down the U.S. European garrison, despite Putin’s moves in Eastern Europe—the 2008 Georgia grab and the 2014 cyber-attack on Lithuania as well as the annexation of Crimea and the continuing war in Ukraine. The 20 total B61-12s at Büchel is a minimum deterrent if ever there were one. The military and realpolitik logic for an independent German Kampftruppe is strong.

To be sure, it would take a giant change in German domestic political attitudes to even begin to talk about a home-grown nuclear force. But perhaps, with the outside world changing so rapidly and so violently, it is foolish to think that Europeans won’t change their attitudes toward security and the need for military power as well.