- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- US

- Contemporary

- Economic

- Military

- World

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- History

In 1989, Soviet leaders finally let go of one of their most valued secrets— one that Western agencies had devoted huge efforts to guessing or uncovering for decades. The secret was the size of the USSR’s military budget. Documents recently acquired by the Hoover Archives show Soviet leaders agonizing over this decision: Was continued secrecy helping or hindering the defense of the Soviet Union’s vital interests? Would disclosure satisfy Western curiosity or open up the Soviet government to demands for more revelations? Did the leaders themselves even have access to the secrets some of them now wanted to disclose?

The struggle over the defense budget tells us a lot about the value of information built on secrecy. It also shows how hard it can be for the leaders of such a system to shed a lie that has outlived its uses, and to win trust.

Soviet leaders rarely published figures that they knew to be false. The Russian archives show that there were generally not two sets of numbers: a false set for publication and a true set for internal use. When the Kremlin wanted to conceal, rather than invent an outright lie, it preferred to mislead by giving out half or a quarter of the truth or say nothing.

Outright lies were rare but did happen. Among them were the Soviet harvest in 1932 (disastrous), the size of the Soviet population in 1937 (decimated by famine and terror), and demographic losses in World War II (catastrophic). And there was military spending.

In 1930 the Soviet government joined the League of Nations disarmament negotiations in Geneva. R. W. Davies has shown that Stalin’s Politburo decided to lie about the Soviet military budget. For a few years the published figure fell below the true one by a wide margin: by 1932, two-thirds of defense outlays were hidden under civilian items, amounting to 7 percent of the state budget. By 1935, disarmament hopes had collapsed and war was threatening, and there was nothing to lose from resuming truthful publication of the rapidly rising total. This was done the following year.

The struggle shows how hard it can be for a secrecy-addicted system to win trust.

Fifty years later, entering talks to limit nuclear weapons, the Soviet Union faced the same problem of truthfulness. Its official statistics had lied for at least a quarter of a century about the true size of the Soviet military budget, reporting only a small fraction of its defense outlays. The official budgetary allocation in 1980, for example, was less than 3 percent of the Soviet gross domestic product. The world was supposed to believe that this tiny sum—less than what the Soviet population spent on sugar and sweets in government stores—supported a military machine of the same caliber as that of the United States, spending 6 percent of its much larger GDP on national defense in the same year.

Why the deception? According to former Soviet officials, the same reason as in 1930: to influence the climate of arms control and armament negotiations. From the 1960s onward, Soviet leaders had been making repeated proposals to the West for balanced cutbacks in military spending, reporting cuts in their own military spending to make the proposals more convincing. Cynically or otherwise, they did not expect the proposals to be acceptable, and so they continued to build up Soviet military spending in secret.

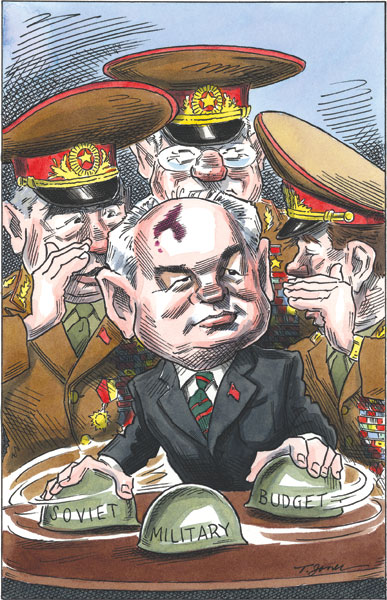

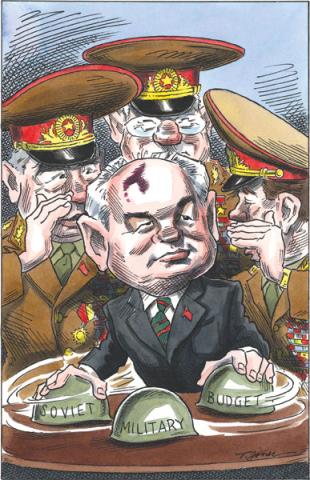

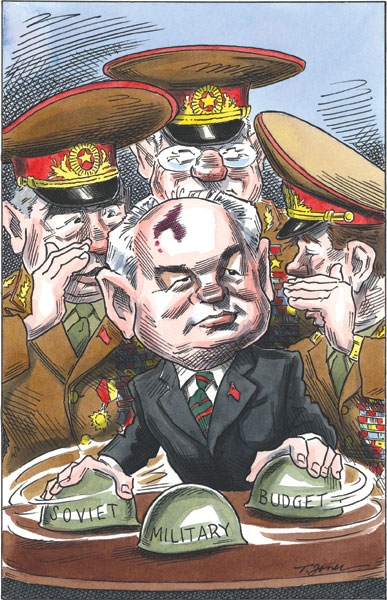

The budget shell game

In the West, the Soviet defense budget was a much analyzed mystery. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency maintained an Office of Soviet Analysis charged with evaluating the military activities and overall economic potential of the Soviet Union. Working out the likely Soviet military budget was an essential part of this work. Doubts about CIA estimates prompted the Pentagon to join in through its Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). A flock of independent scholars, intelligence mavericks, and Soviet emigrants all had their say.

The official defense budget in 1980 was less than 3 percent of GDP. The world was supposed to believe that this tiny sum—less than what Russians spent on sugar and sweets in government stores—supported a military machine equal to that of the United States.

There was no consensus; rather, there was statistical chaos. Take 1980: the lowest Western estimate, 48.7 billion rubles (from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute [SIPRI]), was nearly three times the published figure, 17.1 billion. The highest bid (from the DIA) more than doubled the SIPRI figure, estimating the budget to be 107 billion.

In the Soviet Union, how many people had access to the true figure? According to senior Russian military sources, the answer was four: the party general secretary, the prime minister, the defense minister, and the chief of the general staff. The last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, recalled, "Two or three." Some Western observers speculated that the real answer was zero—perhaps the decades of deception had led to a point where not even the Kremlin knew the true figure.

The Hoover Archives holds the papers of the late Vitalii Kataev, a senior Soviet defense industry manager and arms control negotiator. Those documents show that in 1986 Gorbachev, a new leader, was trying to convince the West that the Soviet Union, although a strategic equal, was not a threat. His credibility, however, was continually undermined by the unconvincing budgetary lie. (Also working against Gorbachev was the Soviet government’s initial silence over the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in April 1986, which badly dented international confidence in Gorbachev’s talk about openness and making a new start.)

On November 21, 1986, the party central committee approved a resolution titled "On Increasing the Openness of the Military Activity of the USSR." The original decree has not come to light, but the Kataev papers include commentary on it by Oleg Beliakov, the central committee secretary for the defense industry. Increased openness, Beliakov wrote, "in the opinion of the USSR foreign ministry, would allow the Soviet side to take up an offensive position in questions of military activity in international forums, and not allow speculation that is inimical to us about the lack of sufficient information on these questions." To consider implementation, the Politburo commissioned a group of four: two deputy heads of Gosplan (the planning board), a deputy head of the KGB, and Marshal Sergei Akhromeev, chief of the general staff.

Mikhail Gorbachev recalled that "two or three" people knew the true Soviet defense budget. Some Western sources speculated that the real number was zero.

Six months passed without progress. In April 1987, Beliakov reported a problem: Gosplan considered it "impermissible" to publish the true defense budget. No alternative was under discussion, however. Beliakov offered a remarkable proposal: "not to publish the actual sum of outlays" but "to proceed by way of artificial formulation of a figure . . . acceptable for publication." The way to do this, he suggested, was to review the defense outlays of the "advanced capitalist countries" and calculate their respective burdens "per head of population and . . . percent of gross national product." A figure suitable for disclosure could then be fixed on two criteria: it "should include the known outlays on defense—20 billion rubles" as a component part; as a percent of GDP it should be "not worse than the developed capitalist countries."

Beliakov was using the joke of the business consultant who, asked to solve two plus two, lowers his voice to ask, "How much do you want it to be?" It is not immediately clear what Beliakov meant by "not worse," but I think he meant "not less": everyone understood that the honest figure was actually in danger of coming out too low, either because Soviet defense costs were lower than the outside world believed or because not all defense costs could be tracked down. The point was to come up with a new figure that did not make the Soviet Union an unequal partner of the United States.

Where exactly did the resistance originate? Beliakov blamed Gosplan, but the planners may have been saying what someone else told them to say. In a personal note, Kataev reflects that "traditionally the military determined the level of secrecy in the country." In his view, Marshal Akhromeev was the chief opponent of disclosure. Kataev related his objections as follows.

First, Akhromeev feared that honesty would do more damage to Soviet credibility than continuing to lie. A truthful figure would come out too low. "Who would believe that the USSR had such a small military budget?" Abroad, the Soviet claim to strategic parity with the United States would look like a "bluff." At home, it would create the impression that "the leaders are deceiving the people under the cover of secrecy."

Second, to defend the truth the Soviet government would have to disclose far more than was originally intended: "One would have to go into the differences in labor and material costs in the USSR compared with abroad and the social channels of redistribution of part of the income in the USSR, and compare the purchasing power of the ruble and dollar."

Third, full disclosure would complicate the market position of the Soviet Union in the global arms trade. Currently, Akhromeev pointed out, Soviet exporters "work at world prices and get a good profit." Informing buyers honestly about the "low production cost" of Soviet military equipment, Akhromeev argued, would undermine the prices they could command.

Finally, Akhromeev saw a significant ideological advantage in continued secrecy: it was useful to encourage "myths about large outlays of the USSR’s budget on military purposes" because they "provided a justification . . . of the low standard of living of people in the USSR."

At some level Akhromeev was following a rule of thumb of Soviet conservatives: You’re in a hole? Keep digging. Go deeper! Is it getting dark? It must be working! The inability to shake off this mentality was a personal tragedy for Akhromeev; when plotters tried to topple Gorbachev and the Soviet government in August 1991, he refused to join the plot but hanged himself when it failed.

Akhromeev’s anxieties resonated with others, and resistance crystallized.

Defensive tactics: compromise and delay

The Kataev collection includes a memorandum from the summer of 1987, prepared for signature by the prime minister, defense minister, foreign minister, a former ambassador to Washington, two central committee secretaries, and the first deputy head of the KGB. Five were Politburo members; this was a heavyweight alliance. The seven accepted that the published figure of 20 billion rubles lacked credibility. They cited the CIA’s much higher estimates of the time—15 to 17 percent of Soviet GNP. They echoed precisely Akhromeev’s reservations: the true figure was too small to be believed and would require additional disclosures to support it; this would incidentally harm the Soviet Union’s foreign commercial relations.

Some Soviet leaders feared that honesty would do more damage to their credibility than continuing to lie. A truthful figure would still seem too low.

The seven proposed compromise and delay. The Soviet Union should announce that the published defense budget was indeed incomplete, covering only the troops’ personal consumption and provisions, military construction, and pensions. Other items were covered by nondefense categories in the state budget. At present, those items were not directly comparable with "the outlays of other countries on analogous uses" because of "fundamental differences in the structure of the armed forces, prices of weaponry, and the mechanism of price formation." Public comparisons of the Soviet and U.S. defense budgets, the seven concluded, "will be possible in 1989 to 1990 after the Soviet Union has implemented the proposed radical reform of price formation in the course of restructuring the administration of the economy," that is, in the next "two to three years." To announce this position would "lift the pressure which has existed for a long time on the question of the size of the USSR military budget."

For a time, therefore, Akhromeev got his way. On August 6, 1987, the Central Committee resolved that defense outlays would be declassified within the next two to three years. In Geneva on August 25, Gorbachev affirmed that the Soviet Union was committed to greater military openness— in principle. The next day, Deputy Foreign Minister Vladimir Petrovskii admitted that the published Soviet military budget, now 20.2 billion rubles, included the maintenance of the troops and so forth and was indeed a fraction of the true total. Shortly afterward, Gorbachev announced that comparable figures for Soviet defense outlays would be made available within "two to three years."

The experts still had to produce a number that would both be credible and meet the objectives of Soviet diplomacy. The accounting was in hand—some of it creative, perhaps. But there was no sign of the "radical reform of price formation" that was to enable Soviet defense costs to be reflected more fully in the budget. In fact, all urgent economic reforms were blocked by political resistance and indecision.

Meanwhile, the clock was ticking. Internally, oversight of the military budget was being delegated to a parliamentary committee of the Supreme Soviet. For review of the 1990 budget, the committee expected to receive figures in the autumn of 1989. Gorbachev was about to visit Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom; what should he tell her about Soviet force levels in Europe?

And the true number is . . .

At last, a new figure began to appear in the documents: 77.3 billion rubles for defense in the 1989 budget, falling to 71 billion rubles in the following year. The original 20.2 billion rubles was there, listed as maintenance, construction, and pensions. The rest of it was munitions and equipment, research and experimentation, and "other." The new figures for 1989 were placed in the context of U.S. outlays on national defense in the same year as follows:

| USSR | USA | |

| Defense outlays, in billions of rubles or dollars | R77.3 | $308.9 |

| Share of state or federal budget | 15.7% | 27.2% |

| Share of gross domestic product | 8.4% | 5.9% |

These numbers clearly met Beliakov’s two criteria for disclosure: they incorporated previously published figures as a component part, and they showed the Soviet Union, with fewer national resources than its superpower rival, to be bearing a heavier military burden relative to its GDP and thus eligible for strategic partnership.

Gorbachev released the new figures in a speech to the Supreme Soviet on May 30, 1989. The long wait was over. Or was it? As Akhromeev had predicted, new questions arose immediately. Skeptics asked, Was this really the full defense budget or were some items still hidden under civilian budget headings? Specifically, what about hidden subsidies to industry: to what extent were defense costs still understated? The second-guessing spread even to Soviet officials; the situation soon became nearly as chaotic as before.

CIA analysts concluded that the true figure for 1989 could be as high as 130–160 billion rubles. Describing the 77.3 billion ruble figure as "a best effort for the present," they suspected that the Soviet administration still did not know the full scale of defense subsidies. The late Dmitri Steinberg put his own upper limit at 133 billion rubles. Such a figure would make the true burden of defense just over 15 percent of the Soviet gross domestic product—close to the much-criticized estimates of the CIA earlier in the decade.

The Soviet economy, as it turns out, was good at making weapons. In an economist’s terms, the Soviet Union had a revealed comparative advantage in military activities.

In short, the new figure was not the whole truth, but it was no longer an outright lie, and probably better than half the truth—a three-fifths truth, say. In this and other ways, the last years of the Soviet Union saw its military- industrial complex gradually pushed out into the light of day.

What can we learn from this story? One theme is the historical burden of secrecy, which is freedom from accountability and the freedom to lie. Secretiveness ran deep in the Soviet system—and not just in military matters. Starting from the conspiratorial, underground origins of the ruling party, it spread everywhere. Secrecy not only prevented political debate and public accountability but also undermined the claim of Soviet leaders to be believed and trusted by the West and by their own people. It made the Soviet economy and society unfit for the age of information and the Internet. It proved to be a crushing burden.

A more subtle point follows. None of the Soviet officials involved in the defense budget struggle saw the USSR as being crushed under an unbearable military burden. Recall the reasoning of Marshal Akhromeev. He wanted to be able to defend the poor state of the Soviet economy in the international arena, and he suggested explaining it by pretending to hide a vast defense budget. But this was a cynical maneuver; honest disclosure would have revealed the defense budget to be small. The Soviet economy, as it turns out, was good at making weapons. Soldiers and equipment were cheap. When the USSR exported arms, it made a good profit—which it wanted to preserve. In an economist’s terms, the Soviet Union had a revealed comparative advantage in military activities. Akhromeev’s rationale stands completely at odds, therefore, with the stereotype of the Soviet Union being driven into bankruptcy by U.S. military spending.

Were the Soviets living in a fool’s paradise? Possibly. If military prices and wages were kept low by conscription and subsidies, then the relative cheapness of Soviet defense was to some extent artificial. Still, even 133 billion rubles was only 15 percent of the Soviet national income. Moreover, the defense burden on the Soviet economy had been close to that rate for years; no sudden rush could have tipped the economy over the edge into bankruptcy.

It would be difficult to say that the disclosure of the Soviet defense budget had any impact on the course of events. Most Western observers accepted it not at face value but as a stumble in the right direction. From an arms control perspective it was probably a necessary but incidental step to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty that Presidents Gorbachev and Bush signed on July 31, 1991. More important for this treaty than budget transparency were the disclosure and verification of Soviet military force levels and deployments in Europe and Asia. For today, the story may be most important as an illustration of how secrecy can become a burden that is hard to lay down and a habit that is hard to break.