- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- Campaigns & Elections

- The Presidency

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

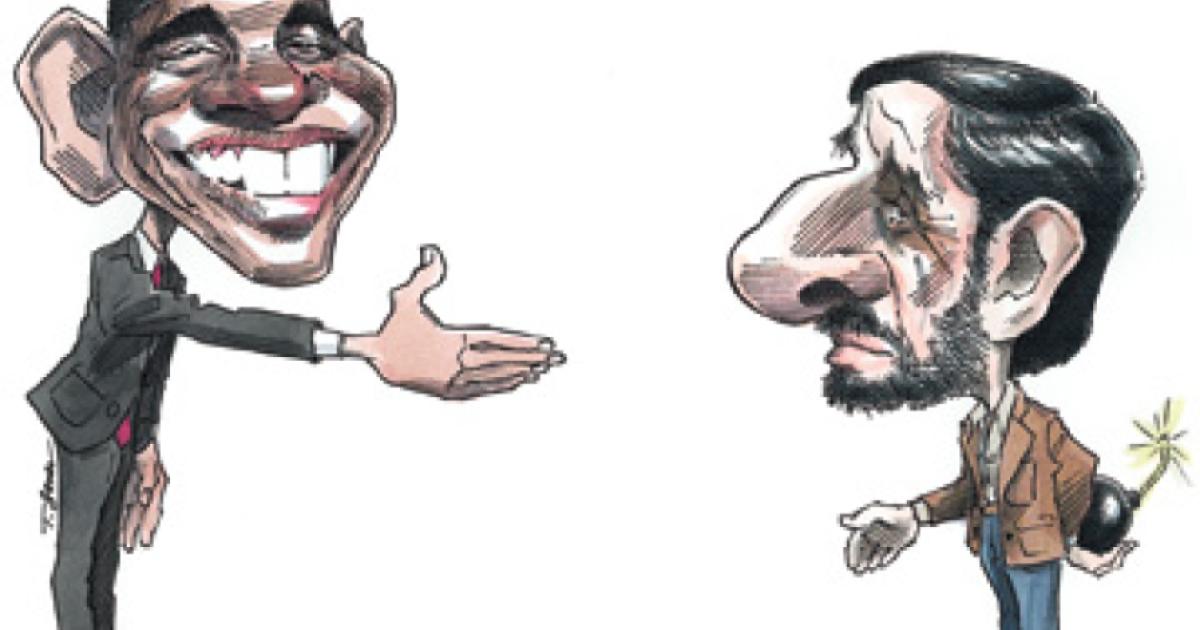

After a Democratic debate last fall, Barack Obama proclaimed that were he to become president, he would talk directly even to America’s worst enemies. One could imagine President Obama as a kind of superhero taking off in Air Force One for Tehran, there to be greeted on the tarmac by the villainous Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Was this a serious foreign policy proposal or simply a campaign counterpunch? Hillary Clinton, Obama’s rival, had already held up this idea as evidence of Obama’s naiveté. Wasn’t he just pushing back, displaying his commitment to “diplomacy”—now the most glamorous word in the Democratic “antiwar” lexicon?

Whatever Obama’s intent, history has given his idea a rather bad reputation. Neville Chamberlain springs to mind as a man who was famously seduced into the wishful thinking that seems central to the idea of talking to one’s enemies. Today few Americans, left or right, would be comfortable with direct talks between our president and a character like Ahmadinejad. Wouldn’t such talk only puff up extremist leaders and make America into a supplicant?

On its face, Obama’s idea seems little more than a far-left fantasy. But perhaps it looks this way because we are viewing it through too narrow a concept of warfare. We tend to think of our wars as miniature versions of World War II, a war of national survival. But since then we have fought wars in which our national survival was not immediately, or even remotely, at stake. We have fought wars in distant lands for rather abstract reasons, and the feeling has been that these were essentially wars of choice: we could win or lose without jeopardizing our nation’s survival.

Obama’s idea clearly makes no sense in a context of national survival. It would have been absurd for President Roosevelt to fly to Berlin and talk to Hitler. But Obama’s idea does make sense in the buildup to wars where survival is not at risk—wars that are more a matter of urgent choice than of absolute necessity.

I think of such wars as essentially wars of discipline. Their purpose is to preserve a favorable balance of power that is already in place in the world. We fight these wars not to survive but—once a menace has arisen—to discipline the world back into a balance of power that best ensures peace. We fight as enforcers rather than as rebels or as patriots fighting for survival. Wars of discipline are pre-emptive by definition. They pre-empt menace to the peaceful world order. We sacrifice blood and treasure not for change but for constancy.

Conversely, in wars of survival, like World War II, we fight to achieve a favorable balance of power—one in which a peace is established that guarantees our sovereignty and survival. We fight unapologetically for dominance, and we determine to defeat our enemy by any means necessary. We do not bother ourselves much over the style of warfare—whether the locals like us, where the line between interrogation and torture lies, whether we are solicitous of our captives’ religious beliefs or dietary strictures. There is no feeling in society that we can afford to lose these wars. And so we never have.

All this points to one of the great foreign policy dilemmas of our time: in the eyes of many around the world, and many Americans as well, we lack the moral authority to fight the wars that we actually fight because they are wars more of discipline than of survival, more of choice than of necessity. It is hard to equate the disciplining of a pre-existing world order—a status quo—with fighting for one’s life. When survival is at stake, there is no lack of moral authority, no self-doubt, and no antiwar movement of any consequence. But when war is not immediately related to survival, when a society is fundamentally secure and yet goes to war anyway, moral authority becomes a profound problem. Suddenly such a society is drawn into a struggle for moral authority that is every bit as intense as its struggle for military victory.

America does not do so well in its disciplinary wars (the Gulf War is an arguable exception) because we begin these wars with only a marginal moral authority and then, as time passes, even this meager store of moral capital bleeds away. Inevitably, into this vacuum comes a clamorous and sanctimonious antiwar movement that sets the bar for American moral authority so high that we must virtually lose the war to meet it. There must be no torture, no collateral damage, no cultural insensitivity, no mistreatment of prisoners, and no truly aggressive or definitive display of U.S. military power—in other words, no victory.

Meanwhile, our enemy is fighting all-out to achieve a new balance of power. As we anguish over the possibility of collateral damage, this enemy practices collateral damage as a tactic of war. In Iraq, Al- Qaeda blows up women and children simply to keep alive the chaos of war that gives it cover. This enemy’s sense of moral authority—as misguided as it may be— is so strong that it compensates for its lack of sophisticated military hardware.

On the other hand, our great military might is not enough to compensate for our weak sense of moral authority, our ambivalence. If we have the greatest military in history, it is also true that we lack our enemy’s talent for true belief. Our rationale for war is difficult to articulate, always arguable, and distinctly removed from immediate necessity. Our society is deeply divided, and a vigorous antiwar movement is ready to capitalize on our every military setback.

This is the pattern of disciplinary wars: their execution is always undermined by their inbuilt lack of moral authority. In the end, our might neutralizes our might. Our vast power makes all such wars come off as bullying, even when we fight selflessly for the freedom of others.

Great power scares unless it is exercised within a painstaking moral framework. Thus, moral authority is the greatest challenge of U.S. foreign policy. This is especially so in wars of discipline, wars fought far away and for abstract reasons. We argue for such wars as if they were wars of survival because we want the moral authority that comes automatically to them. But Iraq is a war of discipline and no more. If we left Iraq tomorrow, there would be terrible consequences all around, but we would survive.

Our broader war against terror, on the other hand, is a war of survival. And it is rich in moral authority. September 11 introduced necessity, and, in its name, we have an open license to destroy that stateless network of terrorism that attacked us. America is not divided over this. It was Iraq— a war of discipline—that brought us division. This does not mean the Iraq war is invalid. Ultimately, it may prove to be a far more important war in preserving a balance of power favorable to America than our war against Al-Qaeda.

The point is that wars of discipline will always have to be self-consciously fought on a moral as well as a military front. And the more we engage in the moral struggle, the more license we will have to fight these wars as wars of survival. In other words, our military effectiveness now requires nothing less than a smart and daring brinkmanship of moral authority.

If Obama’s idea was born of mushy idealism, it could work far better as hard-nosed moral brinkmanship. Were an American president (or a secretary of state for the less daring) to land in Tehran, the risk to American prestige would be enormous. The mullahs would make us characters in a tale of their own grandeur. Yet moral authority would redound to us precisely for making ourselves vulnerable to this kind of exploitation. The world would witness not the stereotype of American bullying but the reality of American selflessness, courage, and moral confidence.

If we were snubbed, if all our entreaties to peace were flouted, if war became inevitable, then we would have the moral authority to fight as if for survival. Either our high-risk diplomacy works, or we have the license to fight to win. In the meantime, we give our allies around the world every reason to respect us.

This is not an argument for Obama’s candidacy, only for his idea. It is a good one because it allows America the advantage of its own great character.