- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

This year’s national election may be unlike any we’ve seen before, especially at the top of the ticket. But a disconcerting constant remains up and down the ballot: the influence of large sums of undisclosed money.

While media coverage tends to fixate on “Super PACs” and key actors on the national stage, a host of individuals and organizations of all political persuasions exert significant influence on our democracy at all levels – from local city council races to ballot measures. And they increasingly do so through secret or “dark” money moving through nonprofits and other vehicles.

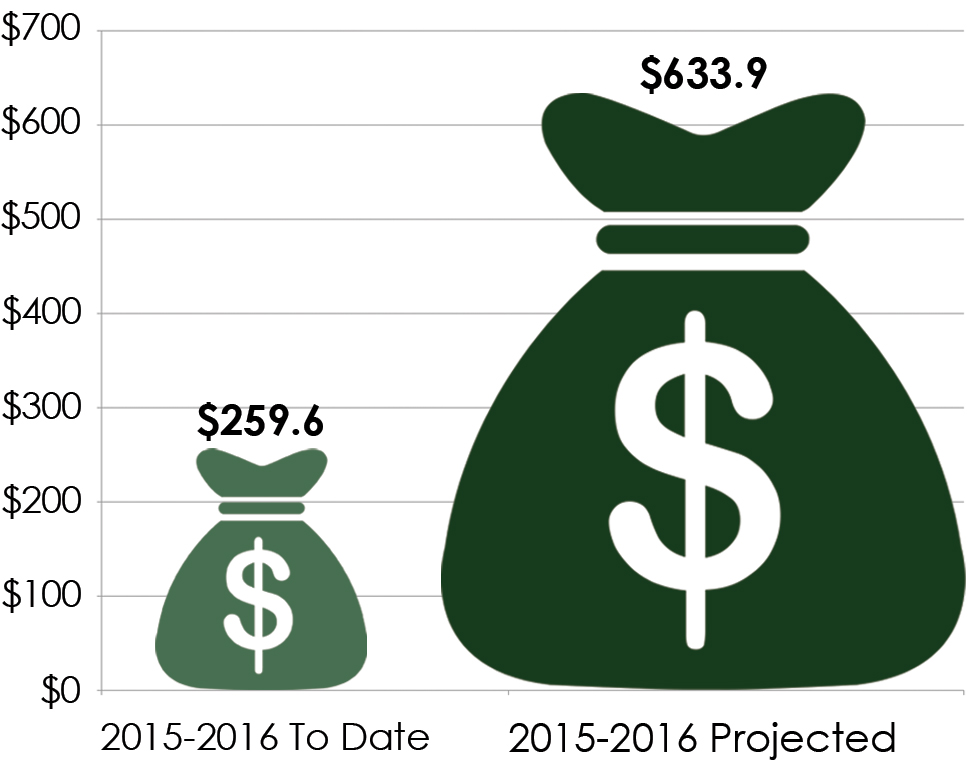

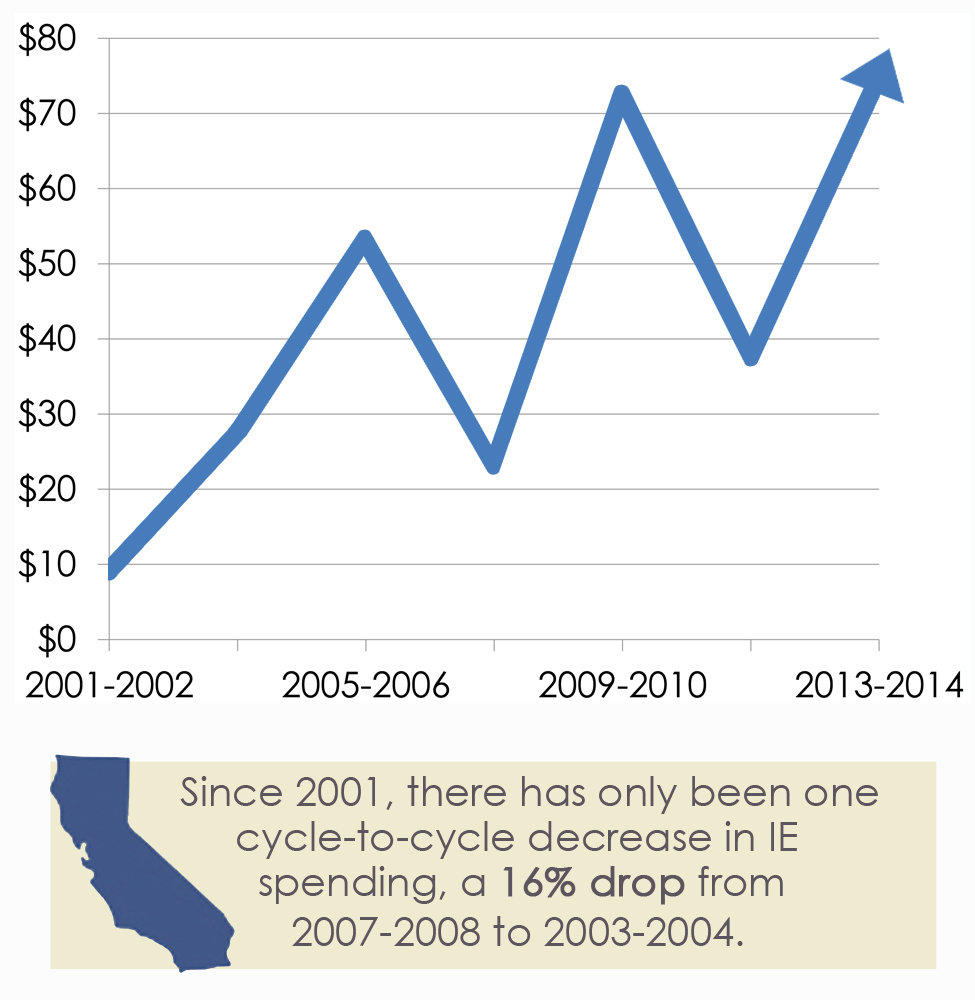

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, "spending by organizations that do not disclose their donors has increased from less than $5.2 million in 2006 to well over $300 million in the 2012 election.” And secret spending at this point in the 2016 cycle is up five times over 2012, a trend that predicts well over $1 billion in dark money this cycle. Despite these statistics, the reality is no one can reliably say who is spending how much to shape decision-making in our country.

The issue is twofold. One: a campaign finance regulatory scheme that cannot keep pace with the “innovations” that subvert it. Citizens United has become a meme used by reform groups discussing the ills of modern campaign finance system. While this ruling was a stepping stone toward unlimited political expenditures, it is only the most prominent of a series of rulings dating back to the Watergate-era that have eliminated existing and proposed restrictions on campaign spending, affirming the notion of political spending as “protected speech.”

This rising tide of political money has fostered a latticework of new and proposed regulations across states and localities. While many of these schemes are well intentioned and perhaps effective in narrow ways, their practical effect is to make true understanding of the scope and scale of money’s influence on our democracy all but unknowable.

Indeed, a robust regime of disclosure, enabled by technology, holds promise for making the “brought-to-you-by” known to citizens. As Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in the Citizens United decision, “With the advent of the Internet, prompt disclosure of expenditures can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters.”

The problem with Kennedy’s belief in real-time disclosure is that loopholes in disclosure law make it possible to hide spending. Just last year in an interview with Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow, Justice Kennedy observed that disclosure is “not working the way it should.”

This leads to the second major issue, outmoded systems for reporting and disclosure. Disclosure documents may not be available until elections are decided, and siloed systems preempt efforts to piece together influence across state lines and varied levels of government. Technology is ready to help, but its implementation by our government is woefully behind.

In California, the central repository of state lobbying and campaign finance was launched in 2000, when most Americans hadn’t yet used the Internet and did not have cell phones. Today, less than one hundred of the state’s more than 5,000 local agencies even have online filings, meaning that if you want to know who is giving to your mayor or school board, you probably have to go to city hall or a district office and sort through reams of paper filings – if you’re lucky, they’re in PDF form.

The bottom line: if you’re wondering who’s pulling the strings, there may not be an answer for you. That is frightening, it’s unacceptable, and it’s going to get fixed.

Last year, some of the leading policy and technical minds in California joined me in starting the Voters Right to Know effort. Our goal: to foster government policy that is better aligned with citizens’ interests and increase citizen engagement with a democracy that they trust. We want to tear down byzantine structures used by special interests to veil their pursuit of election results, and give California and its people the tools to be vigilant in maintaining disclosure. We envision a systemic approach that leverages technology and new disclosure laws to transform the campaign disclosure system and reveal true donors of contributions, not just shell nonprofits with nondescript names.

More importantly, we want to catalyze a culture of disclosure that we believe can – and must – be imbued into our politics at all levels. As Daniel Newman, President and Co-Founder of MapLight, said: "Our research conclusively shows that knowing which funders are behind campaigns makes a big difference to voters. Depending on their opinion of the funder, voters were much more likely to believe – or disbelieve – a particular ad. In other words, this type of disclosure is key to providing voters with the information they need to evaluate political messages to make decisions in their own best interests.”

Right now, the legislature has an opportunity to act on a specific proposal from Voters Right to Know and finally reboot its failing disclosure system. SB 1349 was introduced by Senator Bob Hertzberg last month and includes best practices drawn from around the country, and enjoys broad support from business, labor, and reform advocates. We ceased our initiative signature-gathering efforts after Hertzberg engaged with our team.

Passage of SB 1349 will allow California’s Secretary of State to make this system easy to use – for campaigns, citizens, and the media. With this project, Californians will have among the most reliable, up-to-date, and easily understood view in the country of the money behind campaigns. This will shine a light on the flow of political money. We can envision this helping to align government policy with voters’ interests and to restore civic engagement in our democracy.

But in the future, Californians cannot count on this or any law to be effective at protecting their democracy in the face of campaign finance practices that will develop to subvert citizens’ interests. For that, a comprehensive ballot measure must instruct regulators, legislators, and courts to establish and continuously update laws in protection of a new California constitutional right: a right to know about the sources and spending of election and influence money.

Qualifying for the ballot is a heavy lift. And this is not a ballot measure topic that will yield a financial return to vested interests. It will require committed Californians that are ready to catalyze the tilt back – to a government for and by the people.

California has a heritage of policy innovation that often sets the national agenda. Together with other states, we can show that the people demand equal access to their democracy, and showcase pragmatic steps on the road to that end. It’s long overdue.

SENATE BILL 1349

Introduced by State Senator Bob Hertzberg of the San Fernando Valley, SB 1349 amends the Political Reform Act of 1974 – a landmark ballot measure that created California’s campaign disclosure and oversight regime – to include a public campaign finance disclosure mandate on California’s Secretary of State in addition to public candidate finance filings. In essence it mandates the public identification of major donors to not just candidates, but also independent expenditure campaigns. California is a pioneer in online campaign finance disclosure with the advent of Cal-Access, created by the Online Disclosure Act of 1997.