Drawing on the older traditions of the Prussian army, nineteenth-century Germany grew into a formidable military power, and during the twentieth century it nearly dominated Europe. It took two world wars to defeat Germany and to contain its aggressive ambitions. While the end of the First World War left the German home front relatively unscathed, the conclusion of the Second World War devastated Germany: Most of its cities and industrial infrastructure were destroyed through aerial campaigns, and the occupation by the victorious powers put an end to national sovereignty, leaving the country divided for forty years. In addition, the inescapable need to face the crimes of the Holocaust undermined most vestiges of national self-esteem. All these factors contributed to a widespread revulsion against nationalism and military might. The German legacy of militarism turned suddenly into a culture of pacifism, which centrally defined the political self-understanding of West Germany (not, however, Communist East Germany) and now the unified Germany of the “Berlin Republic.” Germans largely regard their militarist past as a source of shame, and they view the prospect of any military engagement with deep apprehension. Even though German scientists played important roles in the development of nuclear science and missile technology, that was a long time ago: Today’s Germany is no candidate for ambitious military undertakings and certainly not for nuclear weaponry.

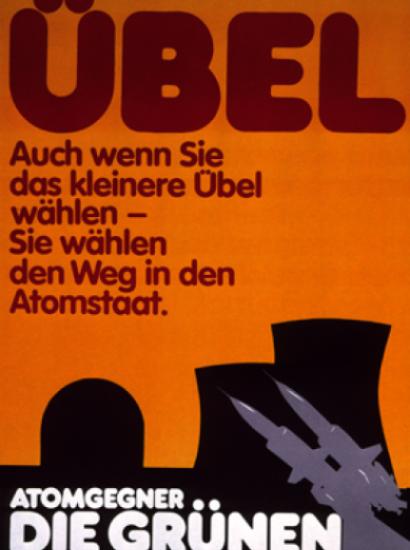

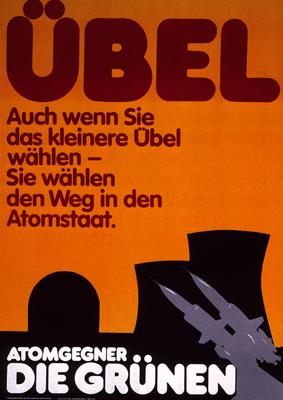

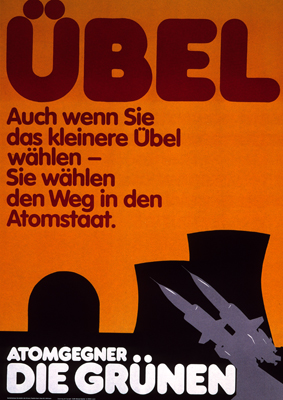

German politics tends to be dominated by the forces of the center-right, which can understand the need for a strong defense, but the government typically faces significant popular opposition to military initiatives. This was true in the 1950s, when West Germany rearmed and joined NATO, but only despite widespread protests. In the 1980s Social Democrat Chancellor Helmut Schmidt supported the deployment of NATO missiles (to counter Soviet armaments), but he faced vocal criticism, especially in his own party and further on the left. After 9/11, Germany did contribute troops to ISAF but only with very strict restrictions on their combat roles, and recently, after the Paris attacks, Germany committed troops to Syria for the war against ISIS, but primarily for the purposes of intelligence gathering. Despite its pacifist culture, Germany does participate in military operations, but only with major restrictions.

Yet while Germany’s twentieth-century past continues to cast a long shadow that limits its willingness to wield military force, the same country has emerged as a significant economic and political power within the European Union. During the years of the Euro crisis, policy made in Berlin effectively defined key European decisions. Angela Merkel’s opponents, especially in southern Europe, attacked her for pursuing German national interests rapaciously. Yet Merkel succeeded because she could persuasively argue that her economic policies were in the best interest of Europe in general. In other words, the German Chancellor has been prepared to use considerable economic and political power as long as she could operate with a European, rather than a national rhetoric. There is a lesson here for the prospects of German military options in the future.

Given the legacy of the world wars, it is unimaginable that Germany will become an independent nuclear power. Domestic political opposition would block it, as would its European neighbors, which harbor lingering anxieties from the world wars. However, if the nuclear question were reframed in a European context, the answer could be quite different. Germany of course already participates in NATO, which places it in a nuclear context, albeit one dominated by the U.S. In the meantime, the EU is searching for modalities for a common foreign policy, and if that difficult quest were to be successful, a common military policy and even a common military force could emerge. Given the German commitment to the EU project, it is likely that it would participate in a joint nuclear force. In fact the Germans might even see their participation as an opportunity to put a brake on the French. While an independent German nuclear force is impossible to imagine, a European solution, with de facto German leadership, is not unrealistic.

France and the UK are already nuclear powers. For them to subordinate their capacities to a European force—a European force that might well end up under German hegemony—would not be an easy step. Such a “European nuclear unification” might however be plausible if the domestic political pieces were to fall into place in the face of a growing Russian threat coupled with an erosion of confidence in the Atlantic alliance. If the U.S. pivots to Asia (or turns inward), the Europeans will have their own choices to make. As of this writing however the internal coherence of the EU is under considerable stress, and its future is uncertain.