- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

A major selling point of the Obama campaign in 2008 was the promise to improve the U.S. image overseas, heal the rifts with traditional allies in Western Europe, and eliminate the anti-Americanism that had burgeoned during the Bush years. In his first term, President Obama undoubtedly began to keep this promise, thanks to his personal charisma, but thanks as well to a fundamental change of course in foreign policy.

Yet his second term has begun with sudden eruptions of precisely that political hostility to the United States that he had promised to end. At stake are not the usual suspects—ideological regimes such as North Korea or Venezuela—but, worrisomely, countries with strong histories of cooperation with the U.S. and in which America has deep investments. Both in Germany and in Egypt—two very different cases, to be sure—politicians and parties have chosen to decry Washington. Anti-Americanism is back.

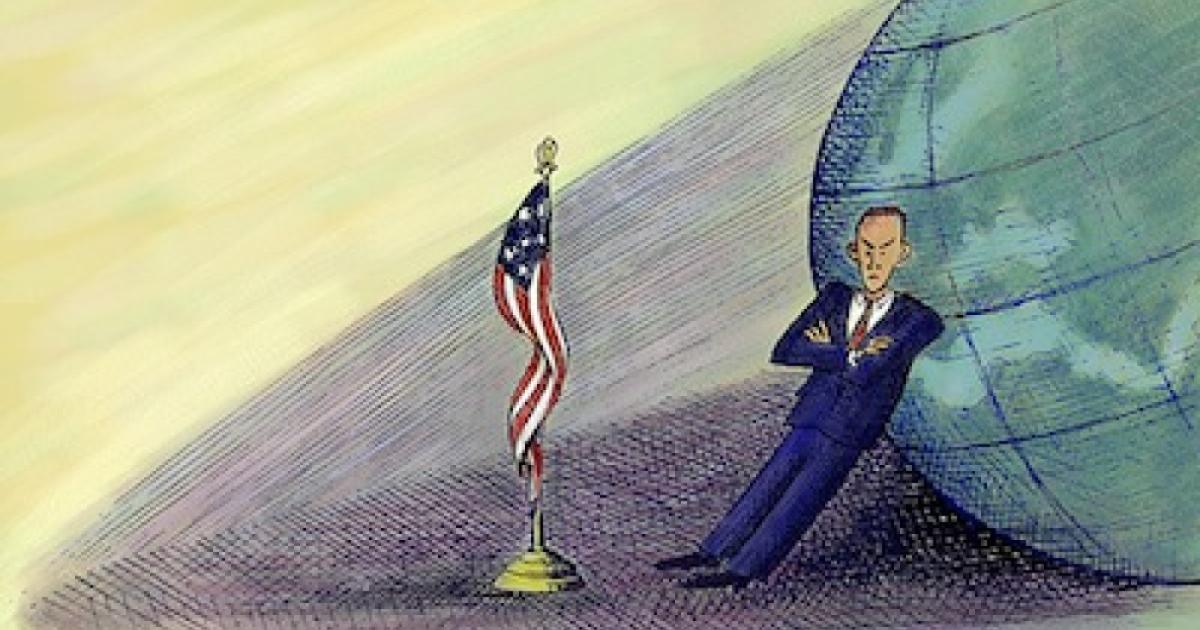

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

For Germany, the NSA affair touched raw nerves. Contemporary Germans have a strong sense of privacy rights, and the memories of the East German Stasi, not to mention the Gestapo, makes them particularly allergic to suggestions of government snooping. In addition, the Snowden revelations hit the news during the lead up to the September elections.

The underdog Social Democrats (SPD) made a calculated decision to attack Chancellor Merkel and the Christian Democrats (CDU) for betraying German interests through collaboration with U.S. intelligence gathering. A hostile press has portrayed America as a demonic surveillance state that combines unlimited spying with targeted killings. Demonstrators directed their animosity toward the U.S. President, with bitterly ironic slogans (in English) like “Yes, We Scan.” Poster’s juxtaposed Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” with an image of Obama tagged with “I have a drone.” The CDU has hit back hard, pointing out that cooperation between German and American intelligence services dates back to agreements reached when a coalition of the SPD and the Greens was in power.

In this pre-election scramble, association with the U.S. counts as a negative. It turns out, however, that most of the impugned cooperation has involved information sharing in Afghanistan regarding terrorists, not harmless phone calls in Germany. Even though the accusation may have been defused, the past month of political mudslinging in Germany points to a potent anti-American reservoir in the political culture that politicians can tap into at will.

In Egypt, the upheavals began with the fall of Hosni Mubarak, the electoral success of the Muslim Brotherhood, and its political miscalculations, that led in turn to massive popular opposition and the intervention of the military with the subsequent bloodshed. In these complex currents, U.S. policy has succeeded only in antagonizing all significant political actors. Mubarak loyalists feel betrayed of course, but so does the Muslim Brotherhood, which believes that America instigated the military coup.

At the same time, the Brotherhood’s opponents, the liberals who seemingly benefited from the military’s actions, resent the continued American advocacy for Morsi and the Brotherhood. The press abounds with conspiracy theories that denounce Obama, as well as Senator John McCain, outing both as clandestine Brotherhood members. Less bizarrely, but even more worrisome, is the warning by Egyptian novelist Mohamed Salmawy, writing in al-Ahram, that the American image in Egypt is worse than it’s ever been.

In many ways, Germany and Egypt could not be more different. Germany is a profoundly stable liberal democracy, while Egypt is anything but that. Germany can boast a strong free-market economy (despite some current softening), while Egypt’s economy is in free-fall and is going to need enormous support from the IMF. Both, however, have enjoyed strong and positive ties to Washington over decades, and both are of considerable strategic importance in their respective regions: Germany as the bedrock of the European Union and Egypt as the most populous state in the Middle East and the genuine foundation of the Arab world. It is therefore especially urgent to understand these sudden anti-American turns in the two political landscapes.

Public opinion offers a partial explanation. While recent Pew Research polling data show that the U.S. enjoys high favorability ratings in most of Europe, the picture is in fact quite mixed. In the UK, 58 percent view the United States favorably, but a significant minority, 30 percent, holds negative views. Matters are worse in Germany, with only 53 percent holding favorable views of America (the lowest rate in western Europe), and 40 percent negative. To put that in context, America’s negative ratings are as high in our long-standing ally Germany as they are in our Cold-War competitor Russia. German politicians who care more about votes than about principles could well be tempted to play the anti-American card in order to fuel an election campaign.

The Arab countries of the Middle East are the region in which the United States is viewed most negatively, and in the midst of that animosity, Egypt is the country that gives America the worst scores: 81 percent negative, which is even worse than the 79 percent in the Palestinian territories, the 70 percent in Turkey, and the 53 percent in Lebanon that view America negatively. For all of the foreign aid support that the U.S. has supplied to changing Egyptian governments, the impact on public opinion has been negligible.

Yet public opinion does not just fall from the sky; it responds to the words and deeds of politicians. Why has Obama apparently failed to deliver on his promise to fix the American brand, particularly in these two strategic allies? His resonant speech in Berlin during the 2008 campaign and his famous address at Cairo University in 2009 each seemed to set the stage for repairing the tarnished American image overseas, but now we face an upsurge in anti-Americanism precisely in Germany and Egypt. Do the presidential speeches make matters worse?

Of course there are, as with all politics, local reasons: the Bundestag election in September and the standoff between the military and the Muslim Brotherhood each invite incendiary formulations. In addition, the suggestion of government surveillance has a particular potency in Germany, while a predisposition to conspiratorial thinking continues to poison the Egyptian public sphere.

Yet these local factors do not explain the coincidence of anti-Americanism erupting in two very different places at the same time.

Something else must be going on. Something coming out of Obama’s Washington is making the American image toxic again.

The anti-Americanism of the George W. Bush era had multiple causes: elections in France and Germany, the echoes of contentious domestic U.S. politics overseas, and, above all, the ambitious nature of the Bush administration’s foreign policy. In the wake of 9/11, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq ensued, followed later by an agenda to spread democracy. That was an administration that put a lot of pressure on the world, and parts of the world pushed back.

The Obama administration has defined itself with a very different program: a consistent pull-back and a programmatic reduction in the projection of American power abroad. Its underlying logic has involved the wager that a less confrontational agenda will diminish the sort of hostility that feeds into anti-Americanism.

By now it is clear, that America has lost that wager. The outstretched hand to Moscow has been slapped. The appeal to Tehran has been dismissed. A great power with a foreign policy of weakness reaps neither respect nor affection. And, for Germany and Egypt, confused messages from Washington have hurt U.S. interests.

The genuine rationale for NSA activity, including cooperation with German intelligence services, has been the challenge of fighting Islamist terrorism. U.S. intelligence has prevented attacks in Germany, most notably the Sauerland plot. Yet because the administration claims, for political reasons, that al-Qaeda has already been defeated and the terror threat is over, it has not been able to mount a convincing and robust defense against Snowden’s whistle-blowing.

Meanwhile, Washington has never developed a compelling response to the Arab spring—leading from behind in Libya, passively watching the slaughter in Syria, and lacking a sense of direction in Egypt. When the U.S. lacks a clear voice on vital topics, we can be sure that our enemies will speak up against us.

For now, all signs point to a Merkel victory in Germany, but the tone of the campaign reminds us of a continued anti-American potential. Sooner or later the SPD and the Greens will be back in power, perhaps in a coalition with the former Communists in the Left Party. Relations with the U.S. will suffer. Predicting the future of Egypt is a fool’s errand, but since nearly all of the political parties rely on denouncing the U.S., it’s a sure bet that relations between Washington and Cairo will face strains, to say the least. The administration’s clumsiness may even manage to break the decades-old relationship with Egypt and force the Egyptian leadership to seek a protector with deep pockets elsewhere.

Instead of healing the rifts of the past, the administration’s foreign policy of weakness has bequeathed a legacy that has emerged vividly in the past months: The return of anti-Americanism.