- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

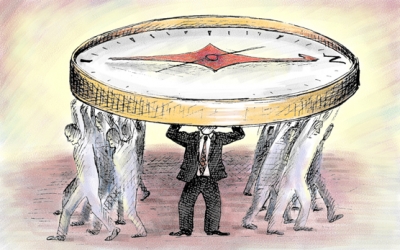

The eighteenth-century Irish statesman and writer Edmund Burke wrote that in democratic governments, "Your Representative owes you, not only his industry, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion." In other words, political leaders should lead, a concept that seems alien to U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk. Citing a recent poll that purportedly showed that a majority of Americans expressed doubts about the value of free trade, Kirk explained that the Obama administration would not push for free trade agreements with other countries.

Despite the inclinations of the lemmings on Pennsylvania Avenue and the ignorance of the American people, free trade overwhelmingly benefits society. It allows a division of labor that encourages countries to focus on those things they produce most efficiently—whether that be manufacturing, technological innovation, agriculture, or the provision of services. Free trade stimulates innovation, raises productivity and creates new wealth, thereby raising living standards. How ironic that the U.S. Trade Representative and his boss, President Obama, seem to be ignorant of these facts, or do not care about them. (Or, perhaps, they fail to factor them into policymaking because of organized labor.)

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Dean Kleckner, chairman of a group called Truth About Trade and Technology and a former federal trade negotiator, pulled no punches in responding to Kirk: "In these trying times, we need men and women with true leadership potential—not cowardly drones who seek merely to join Washington’s herd of poll-sniffing mediocrities."

The urge to sample public opinion and to allow it to shape public policy in inappropriate ways is not new. The U.S. National Science Foundation, a federal agency whose primary mission is to support laboratory research across many disciplines, funded a series of "citizens technology forums," at which previously uninformed, ordinary Americans were brought together to solve thorny questions of technology policy. According to the NSF's abstract of the project, carried out by researchers at North Carolina State University under a grant, participants were to "receive information about that issue from a range of content-area experts, experts on social implications of science and technology, and representatives of special interest groups." This was supposed to enable them to reach consensus "and ultimately generate recommendations" about complex public policy issues, like where national nuclear waste repositories should be located or how genetically engineered plants and animals should be regulated.

The project, first funded to support two panels, and expanded thereafter, called for eight more panels, comprised of people "representative of the local population." Their deliberations were to be overseen by a research team "composed of faculty in rhetoric of science, group decision-making, and political science," who were charged to test both "an innovative measure of democratic deliberation" and "also political science theory, by investigating relationships between gender, ethnicity, lower socioeconomic status, and increases in efficacy and trust in regulators."

Why are we getting policy recommendations on complex technical questions from lay citizens?

This project is preposterous on its face. Moreover, the NSF's left hand seems not to know what its right hand is doing. A study of public comprehension of science by the foundation done several years ago found that fewer than one in four people know what a molecule is, and only about half understand that the earth circles the sun once a year. Even political leaders in policy-making positions are often profoundly ignorant of science. Former U.S. Congressman John Salazar (D-Colorado) related this anecdote: "You know when I was debating what became the 2008 Farm Bill, I had a member of the Ag[riculture] Committee actually ask me if chocolate milk really comes from brown cows. I asked if he was joking and he assured me he wasn't." And Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas), during a visit to the California Institute of Technology’s Jet Propulsion Lab, asked a NASA scientist whether the Mars Pathfinder probe had photographed the flag that astronaut Neil Armstrong had left behind in 1969. Armstrong had, of course, left the flag on the moon, not on Mars. No manned spacecraft has visited Mars.

Former Alaska governor and vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin got terribly muddled with her dismissal of supposedly unworthy government research projects. "Sometimes these dollars go to projects that have little or nothing to do with the public good. Things like fruit fly research in Paris, France. I kid you not." Palin doesn’t know what she doesn’t know. A century of studies on the genetics of the fruit fly, an organism that shares about half of its genes with humans, have been instrumental in understanding how genes work and the process of ageing.

As long ago as 1994, astronomer Carl Sagan expressed concern about the trend toward an American society in which people are "clutching our crystals and religiously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in steep decline, unable to distinguish between what's true and what feels good, we slide, almost without noticing, into superstition and darkness." And in the book, The March of Unreason, British politician Dick Taverne (a.k.a. Lord Taverne of Pimlico) posited that "in the practice of medicine, popular approaches to farming and food, policies to reduce hunger and disease and many other practical issues, there is an undercurrent of irrationality that threatens science-dependent progress and even [threatens] the civilized basis of our democracy."

After all, fewer than one in four people know what a molecule is.

Getting policy recommendations on obscure and complex technical questions from lay citizens (recruited by the NSF in newspaper advertisements) is sort of like getting medical advice from a bartender. Public opinion often cannot distinguish readily between plausibility and provability, nor does consensus among non-experts necessarily lead to valid conclusions. As Nobel Laureate Anatole France observed, "If fifty million people say a foolish thing, it is still a foolish thing."

Why is public opinion on such issues so distorted? One reason is the phenomenon of "information cascade." This is the way in which incorrect ideas gain acceptance by being repeatedly parroted until they are accepted as true even in the absence of persuasive evidence. Many misconceptions about certain disciplines, technologies, or products—such as chemicals, nuclear power, and genetic engineering—arise from the constant drumbeat of dubious accusations from advocacy groups, politicians, and the media. The promotion of technophobia has become a major industry in the United States and Europe.

Another contributing factor is what has been dubbed "rational ignorance," which comes into play when the cost of sufficiently informing oneself about an issue to make an informed decision on it outweighs any potential benefit one could reasonably expect from that decision. For example, citizens occupied with the concerns of daily living—families, jobs, health—may not consider it to be cost-effective to study the potential risks and benefits of nuclear power plants or of plasticizers in children’s toys.

The formulation of public policy can be difficult, to be sure. But if democratic governments are to take public opinion into account, they must discount the ignorance and prejudice of the public when they form policy. Government officials must lead. They must be prepared to explain their actions, and be accountable to their constituents. But these days, science, technology, trade, regulatory policy, and foreign policy often fall victim to a dubious form of governing—governing by the polls. There’s a word for that: pandering.