- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Education

- K-12

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- The Presidency

- Economics

It’s easy to assume that government-financed preschool would do much to cure what ails American education if only it were provided to everybody. Surely, goes the popular assertion—forcefully advanced via heavy lobbying by philanthropists, teachers’ unions, and other education interest groups—helping all four-year-olds prepare for kindergarten will boost overall achievement while narrowing the gaps between poor and middleclass youngsters.

If only life were so simple and public policy so straightforward!

Georgia, Florida, and Oklahoma have adopted universal prekindergarten. New York is among other states moving in this direction—and already supports a half-day program that, in New York City, serves almost 56,000 four-year-olds.

At the federal level, President Obama has promised $10 billion a year for a still-nebulous “zero to five” initiative. His recent economic stimulus package includes billions for early education and child care. That’s on top of Head Start’s $7 billion per annum, the big day-care subsidy for lowincome working parents ($6 billion in federal funds, plus billions more from states), and innumerable other government programs.

Most parents are delighted to share their child care expenses with taxpayers. Yet there’s shockingly little evidence that this costly dash to universalize preschool will do much good for American education, particularly for the kids who most need help preparing for kindergarten. It’s more like a new middle-class entitlement—and an expansion of the public school empire. Indeed, it suffers from a host of basic flaws.

Contrary to proponents’ claims, few preschool programs confer a lasting educational boost. As Berkeley sociologist Bruce Fuller and the University of Maryland’s Douglas Besharov have each found, after exhaustively reviewing masses of studies, nearly all of the gains—small to begin with—wash out within the first few grades. That’s not preschool’s fault as much as the failure of regular public schools to do right by their young pupils, particularly poor kids.

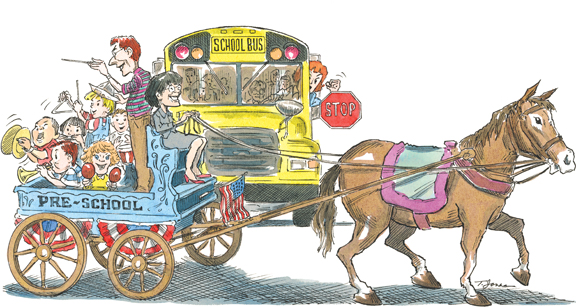

Yet those same ineffective public schools, keen to grow their enrollments, funding, and employee rolls, typically dominate universal-style pre-K programs and squeeze out a thriving private sector.

Thanks in part to that private sector, the vast majority of four-yearolds already have access to preschool—85 percent if we also count day care—and it’s not clear that many more parents want others to mind their children. (Participation rates in the “universal” states, as in New York City, hover in the 50–60 percent range.)

Much of the enormous public investment that we’re already making is ill-spent, at least if school readiness is the goal. The worst offender is the beloved Head Start program, which waves the “child development” banner while shunning the structured teaching and learning (e.g., shapes, colors, sounds, letters) that would truly assist kids to succeed in the early grades.

While advocates insist that many current programs are low quality— and I’ve seen some I wouldn’t want my little granddaughters in—they’ve failed to set and live by quality criteria tied to school readiness. Unlike K–12 education, which has been adjusting—painfully—to being judged by its results, the preschool world clings to “input” gauges (e.g., expenditures, adult-child ratios, teacher credentials). To its credit, Florida rates preschool providers on their graduates’ preparedness for kindergarten. Yet lobbyists have cramped Tallahassee’s ability to banish weak operators, and when federal officials sought to use such measures for Head Start, interest groups made Congress call a halt.

We must also recognize the contradiction in advocates’ dual promise: if gap closing is the goal, universal programs don’t get us there. In fact, they usually do more for the haves than the have-nots. To boost the school success prospects of seriously challenged kids—chiefly daughters and sons of poor, young, single moms with little schooling of their own—policy makers need to focus intensive educational help on them, starting at birth and involving their parents. That’s not cheap, but the sums already flowing into—and promised to—this field would suffice if properly targeted rather than spread over millions of families that don’t need it.

“Child development” alone won’t get this job done, however. Effective preschool programs for disadvantaged youngsters have purposeful learning goals, structured curricula, and objective measures of progress. They give families plenty of choices, including private, community, and churchoperated centers, as well as public schools. And they judge all providers on the basis of performance, above all their wee graduates’ readiness to succeed in the K–12 education to follow.

We won’t get far, though, if we fail to tackle the schools into which these kids proceed. Even the best of pre-K programs cannot overcome kindergarten and first-grade classrooms with weak teachers, slipshod curricula, and low expectations. Done right, preschool is valuable; done in isolation from the rest of the education system, it’s just more pricey water sprinkled on the desert sand.