- World

- Contemporary

- International Affairs

- History

On February 2 of this year, an era came to an end in Central Europe as Czech president Václav Havel stepped down after 13 years in office. By dint of moral authority and spirited leadership, Havel became the face of the 1989 Eastern European democratic revolutions in the same way in which the crumbling Berlin Wall became a material monument to freedom. It was Havel the dissident playwright who repeatedly confronted the Kremlin’s stooges in Czechoslovakia. And it was Havel the statesman who led the people of his country from the 1989 Velvet Revolution to democracy. Across Eastern Europe and the world, Havel captured headlines and hearts.

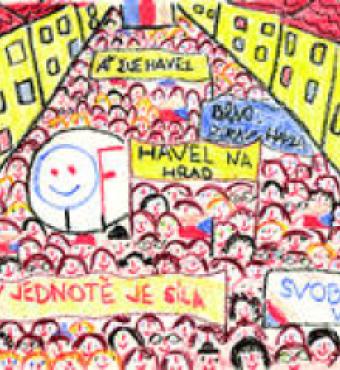

But what is his place in history? Havel has achieved much as head of state. He led his country from the defeat of communism in 1989, to its first free elections in 1990, to its economic revival, and to its reincorporation into the international community—into NATO and soon the EU. The Velvet Revolution street crowds cried out for “freedom,” “democracy,” and a “return to Europe.” The achievement of these goals on Havel’s watch certainly represents a significant presidential accomplishment.

Yet it was Havel’s earlier uncompromising resistance to an oppressive regime that constitutes his greatest legacy. “I often had to smile to myself,” Havel has said, “at how I came across as a fairy-tale hero, a boy who, in the name of the good, beat his head against the wall of a castle inhabited by evil kings, until the wall fell down and he himself became king.” After 1989, Havel’s fame indeed skyrocketed to fairy-tale heights: His work was published in a number of languages, and several biographies of him appeared on the bookstands.

Despite this deserved acclaim, Havel remains something of a mystery to Americans. We know that “dissidenthood” brought him three prison sentences, a ban on his plays, and fame and sympathy abroad. But it is often the less-visible daily grind of persecution that wears down even the most courageous soul. This is especially true of creative people, who need freedom to fuel their imaginations. The rich archival holdings at the Hoover Institution shed light on the extent to which Havel’s everyday life and work were hindered by countless daily annoyances, big and small, and help us gain a better appreciation for the magnitude of his courage in the face of hardship.

The Hoover Collection

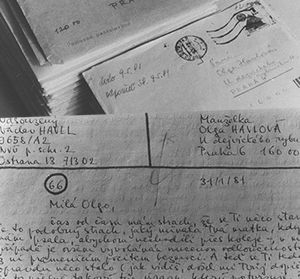

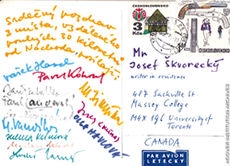

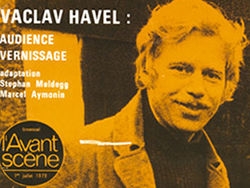

One of the most unique archival possessions at Hoover is the Josef Skvorecky collection. Skvorecky, another Czech literary figure, emigrated with his wife in 1969 to Toronto, where they started a Czech publishing company. The main publisher of Havel’s works in both Czech and En-glish, Skvorecky corresponded frequently with the playwright and staged some of his plays at a Czech-language theater in Toronto. This collection contains many of the letters the men exchanged in the 1970s and 1980s, including postcards, manuscripts, instructions, photographs, and playbills for Havel’s plays from theaters around the world. There are also letters in Czech, Slovak, English, German, and French that Skvorecky exchanged with other people striving to keep the Czechoslovak literary scene alive.

Other collections hold copies of Czech samizdat magazines from the communist era and originals (many signed) of samizdat editions of plays, books, and collected poetry by Havel and others.1 An original 1983 samizdat copy of Havel’s Letters to Olga, a compilation of 144 letters that he wrote from prison to his wife, is also housed in the Hoover Archives.

A collection of post-1989 essays by Pavel Zacek, historian and journalist, analyzes the struggle of Czechoslovakia to come to terms with its past. As a member of the Committee for the Documentation and Inspection of Communist State Security Activities, Zacek reviewed secret files that the communist State Security (StB) kept on Czechoslovak citizens. His 1994 study of Havel’s file, including extensive quotations from the StB notes and documents, is of special interest. These and various other materials paint a picture of Havel’s life before he became a household name.

Chipping Away at the Castle Walls:

The Man and His Work

Havel was initially not a political figure. He possessed, however, a great ability to inspire others, entering public life during the 1950s as the leader of a young literary circle. His “bourgeois” family background barred him from official studies, but he pursued evening high school classes and distance learning at the Academy of Musical Arts. He found his way into the theater with the help of family connections, making his name in the 1960s by writing plays for Prague’s Theater on the Balustrade. By the middle of that decade, however, the increasing encroachment on the arts by the government led him into political life. Initially, he threw himself into the struggle to save the literary magazine Tvar (The Face), which was being shut down for straying too far from officially sanctioned ideas. He collected signatures around the country and organized a youth group to try and keep the magazine alive. This activity, in the end unsuccessful, earned him the scrutiny and harassment of the StB for the rest of his life under communism, and, in the wake of the suppressed Prague Spring in 1968, he and his works were banned from the theater.

Seeking to take a break from his political activities and focus on his literary work, in the summers after 1968, he and Olga invited their literary friends to spend weekends at their country house in Hradecek, where they could get away from Prague, relax, discuss literature, and even host concerts of forbidden music. But this escape was not always easy to realize. “It’s a paradox,” Havel wrote to Skvorecky in 1983, “that my greatest wish is to retreat to Hradecek, write a play and take a break from ‘dissidenthood,’ and that it is precisely this [police] harassment that foils my plan, however desirable from the standpoint of the police it may be.”

In his epilogue to Letters to Olga, Havel’s friend and co-prisoner Jiri Dienstbier wrote that Havel was afraid that the attention his political activity attracted abroad would thrust him into public consciousness as a “professional revolutionary” or a “dissident.” Wishing to be known first and foremost as a writer, “he didn’t want to be perceived as a ‘cruising missile’ in the duel of the powerful, but as a person who is concerned about the meaning and horizons of human existence.” This wish was not to be granted, at least not in the short term.

Ironically, Havel experienced the first direct intrusion into his life by StB agents in 1965, when they tried to recruit him as an informant. Pavel Zacek writes that the agents hoped to exploit Havel’s contacts with an alleged U.S. spy at the American embassy. Havel was so polite to the intruders in his flat that they concluded in their report that he “appears to be an appropriate agency type.” They changed their minds just three months later and began to watch him closely. Using K-3, E-4, and G-9 (StB codes for mail censorship, phone bugging, and removing items from the home), the StB learned details of Havel’s “subversive” activities—his involvement with Tvar and with citizens’ groups. They also found a speech that Havel was planning to give at a PEN writers’ conference in New York—a discovery that was likely behind the decision to deny Havel an exit visa to attend the conference.

In 1979, Havel was charged with subversive activity hostile to the state. The arrest was triggered by his participation in a citizens’ initiative called Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Persecuted (VONS), which issued alerts regarding persons prosecuted and imprisoned for exercising their constitutional rights. Havel believed strongly that citizens should exercise their right to freedom of speech and association even if such behavior was punished by the state. Now unjustly charged himself and held without trial for months, Havel held onto this belief. In his self-defense speech at the trial he openly admitted his activities and argued that they were legal:

International pacts about human rights, which became part of the Czechoslovak legal code, dictate that not just state authorities, but citizens have a duty to monitor how the rights guaranteed by these pacts are respected in their country. As a citizen of this country I personally took this duty onto myself because I believe that human dignity, freedom and justice are indeed matters of the whole society, that we all, without exception, are responsible for them and that we all, without exception, should draw attention to cases when we feel these basic values are threatened. My work in Charter 77 [an informal group of human rights activists] and my participation in the work of VONS were based on this perceived and accepted ethical and societal responsibility.

. . . I do know that I had an unalienable right to take these actions—regardless of how unpleasant this was to the state.

Havel became such a gadfly to the authorities that they offered to let him emigrate to the United States with Olga. The offer came during his stay in prison, when he was still awaiting trial and expecting a long sentence and therefore had a strong incentive to concede. Mocking this attempt to get rid of him, he brought this offer to the attention of the court:

I have a reason to assume that if I had responded positively to this inquiry, I could have been in New York at this time, occupying myself with the theater. If I am standing in this courtroom instead, it is then clearly out of my own choice. A choice, which—I believe—does not prove my hostility to this country and which was based on—among other reasons—my intention to state clearly that I do not consider myself guilty and that I am not losing my faith in justice.

Havel actually had other opportunities to escape to a more comfortable life. Skvorecky invited him to come to the University of Toronto as a writer in residence for the academic year 1985–86. “I personally think that you have already done and suffered for the cause more than enough and you have the right to a more peaceful life,” Skvorecky wrote in late 1983. Havel, at first tempted by this opportunity to travel, write, and teach theater, in the end replied to Skvorecky in January 1984 that he had to refuse. He had a feeling, he explained, that he would

walk away from something from which it isn’t decent to walk away, and that I would disappoint many people. . . . I am not trying to overvalue myself and my importance, but I am a realist and again and again (with a certain dislike) I come across the fact that so many eyes are watching me and expectantly wait to see—some with fear and others with hope—whether I take this step. Someone else wouldn’t care, but I do, being so to speak addicted to my responsibility.

And so Havel continued to “hit against the castle wall.” In addition to his ongoing struggle with the regime, he had difficulty getting his works published and performed. His plays, which generally mocked the absurd characteristics of socialist society, were forbidden after the Prague Spring. Except for one illegal performance, he did not see his creations on stage again until 1989. Disheartening as this was, Havel could take some satisfaction in the fact that his plays continued to be published and performed abroad, mostly in Germany and Canada but also in France, Italy, and other countries. It was, however, a cumbersome process, as he was never sure that his manuscripts—or letters regarding them—reached their destination. Important communications had to be confirmed with a postcard or another letter.

Far worse was his inability to review what was actually going into print. With manuscripts traveling through the dissident world in unpredictable ways, Skvorecky somehow got his hands on an early working copy of a play and published it with the agreement of Havel, who thought it was the final version. Despite the error, Havel was grateful that at least one version of the play had seen the light of the day.

There were numerous other obstacles. Books published abroad had to be smuggled back into Czechoslovakia in small numbers and then secretly passed to only the most trusted hands. Typists who copied the books exposed themselves to danger and thus were hard to find. There was no legal system for the direct transfer of royalties. In a September 1983 letter, Havel instructed Skvorecky to send payment through a Czechoslovak firm in Frankfurt, which provided money transfer services that sent cash directly to the home of the payee. Correspondence between the author and the publisher abroad became impossible during Havel’s stays in prison, where inmates were only allowed to write to close relatives. During one such period in 1976, Havel’s brother Ivan took up his correspondence with Skvorecky and memorized the messages that the two wanted to send each other.

Hoover media fellow Andrew Nagorski describes the intent of communist holiday parades and the omnipresent propaganda slogans as not so much to present a sham successful society as to isolate dissent. By making it seem that everyone actively supported the regime, such masquerades made people feel helpless and alone in their dissent, preventing them from speaking up. Most people, the “silent majority,” chose to bow their heads and not risk the little they had. But Havel took on his citizen’s duty to act, despite his initial dislike for politics and despite the immense cost to his personal life and theater career. He later commented that he was a bit sad when in 1992 the Ministry of the Interior sent him a certificate stating that he had not been a “knowing collaborator” of the communist regime: “When I remembered the more than 500 times in my life that they tortured me with endless interrogations, how they jailed me, undertook terrorist raids into my apartment, persecuted all my relatives and friends, destroyed my car . . . it is a sad result of all this to receive a piece of paper where someone states that I was not a knowing collaborator.”

Whatever the judgment of history about his political career, President Havel has no reason to worry about his legacy. His resolute stance against oppression, in matters big and small, in public and in private, will speak to Czechs and lovers of freedom everywhere. It will ask them if they would have acted the same. And will they, should the future demand it? Havel’s example will prompt such self-reflection for generations to come, in those who still struggle against injustice and those who are free. He may have been a statesman and he may have been a playwright, but first and foremost he was a man who stood up for freedom and justice—and that, according to his own wish, will be his bequest to the world he leaves behind.

NOTE

1. Samizdat literally means “self-published.” Literary works that were not officially approved had to be reproduced and circulated in secret. Since professional printing technology was unavailable for unauthorized publications, books were copied by hand with the use of a typewriter and carbon paper. The potential for error was great, and authors’ signatures were an attempt to control quality.