- Economics

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- US

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- History

In some respects the world is more peaceful today than for many years. We forget how much bloodier were the conflicts of the past. In World War II, for example, three hundred U.S. troops were killed on an average day; this fell to fifty a day in Korea, twenty a day in Vietnam, and two a day in Iraq. While Americans are not the only people who die in wars, this serves to illustrate the tendency.

Recent books by Azar Gat (War in Human Civilization), Joshua Goldstein (Winning the War on War), and Steven Pinker (The Better Angels of Our Nature) suggest that the level of violence in human society is in long-term decline. The rule of law, these scholars suggest, has expanded within and between states; commercial and humanitarian motivations are taking the place of blood and soil; peacekeeping works.

Despite this, the world still has the capacity to surprise and disquiet us. In 1913, after a century of the Pax Britannica, few would have predicted thirty years of territorial wars and mass killing. In 1990, the end of the Cold War was widely expected to inaugurate an era of peace and reconciliation, not the decade of ethnic conflict and civil wars that actually followed.

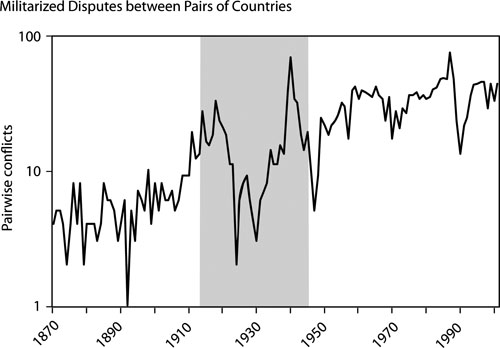

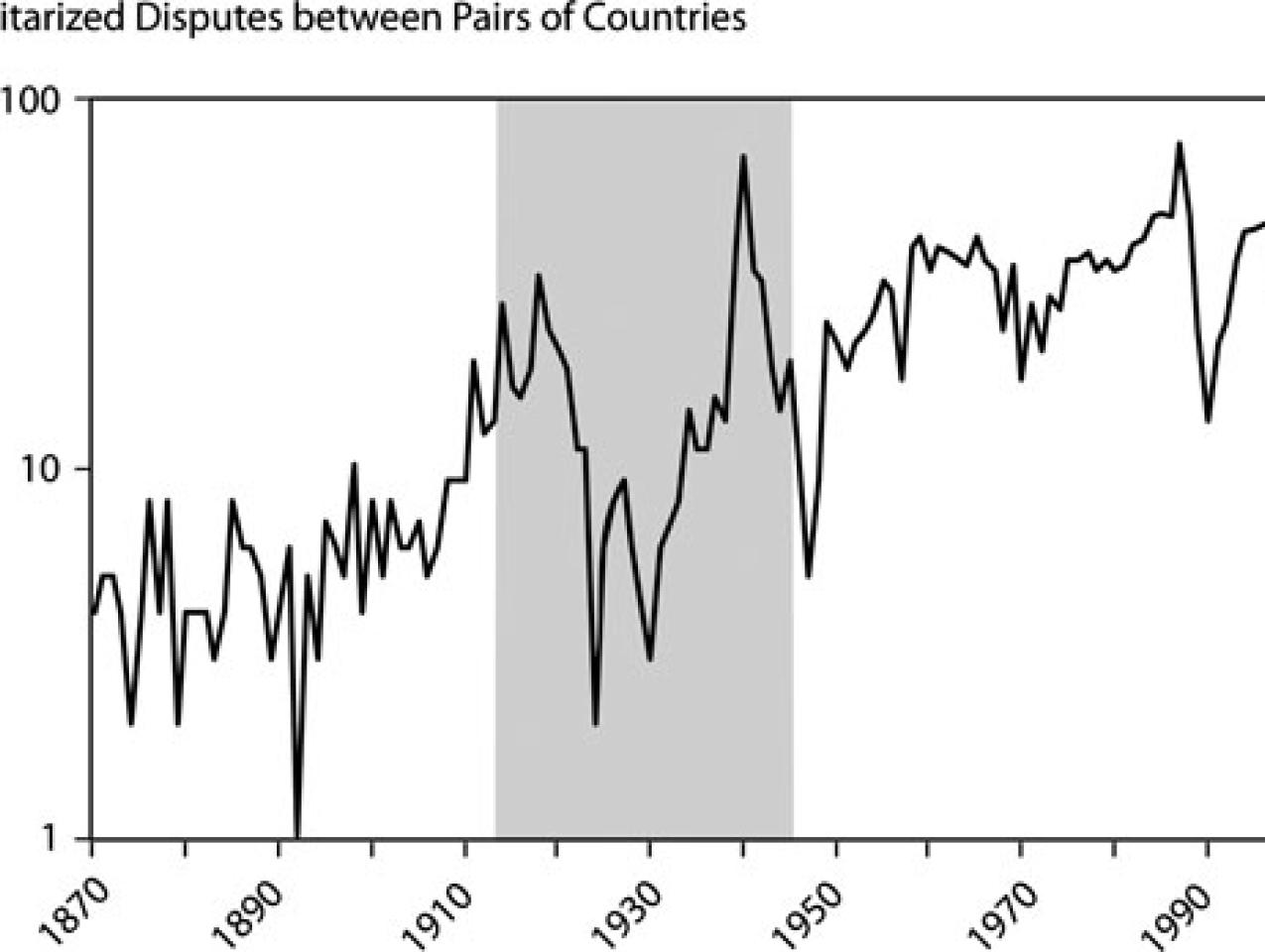

Figure 1

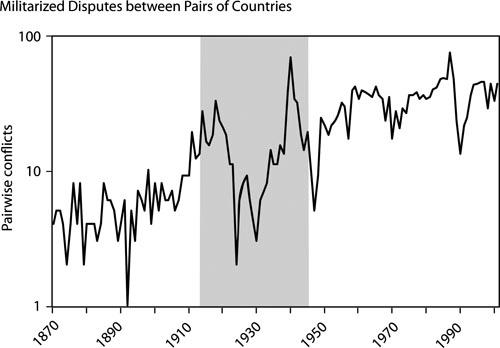

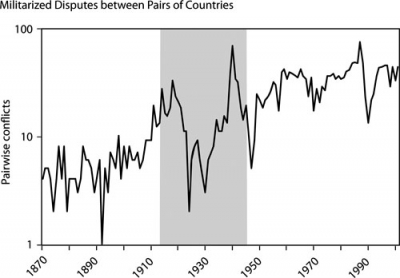

My work (done with Nikolaus Wolf of Humboldt University, Berlin) was inspired by the discovery of a simple and disturbing fact, illustrated in figure 1. The number of conflicts between pairs of states around the world has been rising since 1870. (“Pairwise conflicts” are measured by the number of pairs of countries in conflicts. Conflicts include all uses of military force, from displays such as sending warships and closing borders to full-scale shooting wars. Because we look only at wars between states, civil wars are not counted. This chart uses a logarithmic scale, partly to give a clearer view at the lower frequencies.)

The number of conflicts has been rising on a stable trend; this means that there has been a significant tendency for the year-on-year increase, around 2 percent, to remain the same over the whole period. Two world wars disturb the series between 1914 and 1945. Remarkably, after 1945 the frequency of wars snaps back to the same upward course as before 1913.

Something that continued for one hundred and thirty years must have deep causes. Before these, however, think about some immediate factors. The number of pairwise conflicts is driven arithmetically by two things: the probability that any one country will be drawn into conflict with another, and the number of countries. Since 1945 the number of countries has risen by a lot—so much so that, over the whole period, the probability of any two countries being in conflict has not risen. More pairs of countries have clashed because there have been more pairs. This might seem to reassure, but should not; it just shows that there is a close connection between wars and the creation of states and new borders. Besides, however many countries there are, we have only one planet to share. The growing number of states, and the rising number of conflicts, must all fit onto our planet’s surface, which has a fixed extent. We have already seen two world wars. As those experiences suggest, you can never be sure what little conflicts will suddenly snowball into much wider, more deadly struggles.

Figure 2

NOT JUST “AMERICA’S WARS”

It is also of interest to ask whether some particular group of countries is responsible for the rising trend. Does the rising number of conflicts have a common source? When we have presented our work before audiences, the most frequent questions have been about the extra wars since 1945: “Aren’t these just America’s wars?” and “Aren’t there more coalition wars in which America does the fighting and others join symbolically without firing a shot?”

“No” is the answer to both these questions. Coalition wars are not the explanation. Philippe Martin, Thierry Mayer, and Mathias Thoenig have shown that the average distance between countries at war has fallen steadily and substantially since the 1950s. As for America’s wars, figure 2 provides most of the answer. This figure looks specifically at countries that initiated each of more than three thousand conflicts from 1870 to 2001. When a country goes to war, it does not necessarily signify aggressive plans or a militaristic society, but it does signal readiness to reach for a gun when tension rises. Scan the figure from left to right, and you will see the increasing density of dots; this shows the rising frequency of wars. On the vertical scale, every conflict is linked to the country that initiated it, and each country is placed in the global distribution of national income per head, from poorest at the bottom to richest at the top.

The figure shows that richer countries have been no more likely to make war than poorer countries, and this has hardly changed over one hundred and thirty years. The readiness to embark on military adventures is spread uniformly across the global income distribution.

The important thing is not how rich you are, but how big. Countries with larger economies (defined by the size of their GDP) are more likely to throw their weight around. Luxembourg, for example, is one of the world’s richest (but smallest) countries and has started only one war. America has started many wars. But this is because America is big and this is what big countries do. America is not uniquely warlike or imperialistic. The top ten list of countries that have initiated the most conflicts since 1870 provides revealing context. With the world’s largest economy, the United States comes in second place (originating 161 conflicts out of more than 3,000), behind Russia/USSR (219). The United Kingdom (119) is fourth, following China (151). Germany (102) is sixth, after Iran (112). France is tenth, after Israel, Turkey, and Iraq. The presence of countries like Russia and China illustrates clearly the point that size matters, not prosperity; they are great powers without being rich. Finally, if we completely remove “America’s wars” from our data, the global trends we are concerned about are unchanged.

The rising frequency of wars is disquieting. It is also a puzzle. Much of what we know, or think we know, says this should not be happening. The countries of the world have tended to become richer, more democratic, and more interdependent. The thinkers of the Enlightenment held that these things ought generally to make the world more peaceful. Much political science, including work by scholars such as Hoover’s own Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, demonstrates that the political leaders of richer, more democratic countries have fewer incentives to make war and are more constrained from doing so.

These ideas contain important truths, and we do not think they are wrong. But they are incomplete. The world has become richer and more democratic; why has peace not crowded out conflict? Without being certain of the answer, we think political science has focused too much on preferences for war (the “demand side” of the political actors) and not enough on capabilities (the “supply side” represented by economic and state capacities). Capacity may be the missing factor in the story of the rising frequency of wars. The same factors that should have depressed the incentives for rulers to choose conflict are also increasing the capacity for war.

In other words, we are making war more frequently, not because we want to, but because we can.

Several examples suggest how this can work. First, we live in an age when mass destruction can come out of a suitcase. Since the fifteenth century, starting in Europe, economic growth has made destructive power steadily cheaper, and not just absolutely cheaper but cheaper at a faster rate than for civilian goods. Second, the key to acquisition of destructive power was that modern states became able to tax and borrow more than ever before. The growth of fiscal capacity has been revolutionized several times since the sixteenth century: first by the rule of law, again by democracy, and a third time by the modern dictators. Third, globalization has also played its part. War is disruptive of trade, but they do not exclude each other. As trade costs have fallen, those countries that have maintained long-distance trading links in wartime have been able to fight their neighbors more effectively as a result.

Finally, statehood has become cheaper. As Alberto Alesina and Enrico Spolaore have argued, globalization has made it easier for small nations and ethnic minorities to seek independence and national sovereignty. But with sovereignty comes the power to choose between peace and war, and new nations have often found themselves at odds with their new neighbors. Edward Mansfield and Jack Snyder have written about how new, fragile democracies sometimes build nationhood by engineering conflicts with neighbors.

In other words, the very things that should make politicians less likely to want war—productivity growth, democracy, and trading opportunities—have also made war cheaper. We have more wars, not because we want them, but because we can. Under present international arrangements this tendency is deeply rooted, and it is not something that any one country is going to be able to control.

A MORE COMPLEX PICTURE OF VIOLENCE

What needs to be done for a better understanding of these problems? How can we understand the contrasting trends that we and others have identified in a unified picture?

The data we have used cover conflicts between nation-states. This is an important limitation. In reality, there is a continuum of organized violence from the criminal end of the spectrum through civil conflict and domestic and international terrorism to interstate warfare. In history, one kind of violence easily spills into another. Civil war has led to terrorism and vice versa. An interstate war that ends in conquest can lead to civil war. Terrorists engage in organized crime and acts of war at the same time.

Our major databases are great achievements in their own right, but they artificially segment the spectrum of collective violence, hindering a unified overview. The statistics they hold are limited by the states and borders existing at each date. When civil war broke the Yugoslav state up into several new countries that then fought each other, the violence continued seamlessly; there was a unified process to which the formation and destruction of states and state borders was endogenous. But our statistics show this as discontinuity: one database shows that a civil war ended, while another shows that an interstate war began. Unified data and a unified understanding of propensities to collective violence are the next challenge.