- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

The shooting of seventeen-year old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida on February 26, a tragic loss of life, rapidly spiraled into a national spectacle involving a toxic mixture of race and violence. NBC added fuel to the flames by broadcasting an edited version of remarks by the alleged shooter, George Zimmerman, distorting his words in a way that seemed to corroborate the narrative of racial-profiling.

The White House also seized the opportunity to leap into the fray, adding a national political dimension to local crime enforcement, presumably to rally the Democratic base in the upcoming presidential election. The responses to the killing, whether in the media, politics, or the general public, have played out against the backdrop of our persistent anxieties about race, a legacy of the American past of slavery.

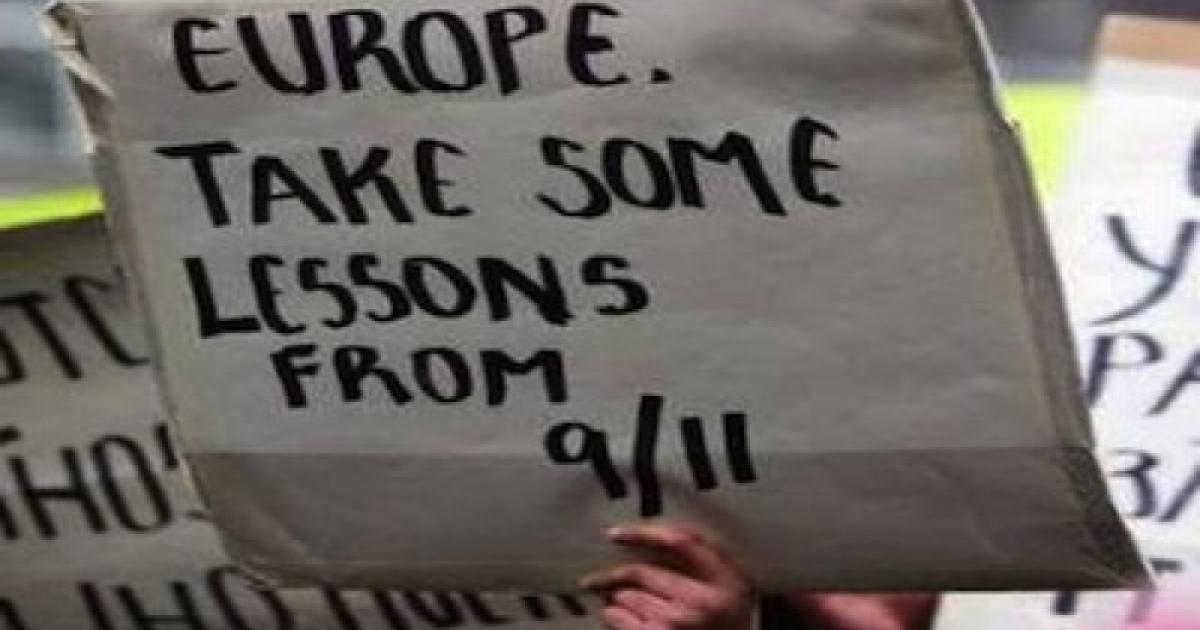

As American as the Martin shooting was, it is worthwhile to look across the Atlantic and to consider the growing frequency and virulence of parallel events there. Race and violence—and their politicization—are by no means exclusively U.S. phenomena. On the contrary, contemporary European societies display similar troubling tendencies, marked by the fragmentation of ethnically-mixed populations, the spread of extremist ideologies, a growing willingness among radicals to engage in violence, and the propensity of politicians to instrumentalize racial and ethnic anxieties for electoral purposes.

Photo credit: SS&SS

America and Europe have more in common in these areas than is commonly expected. Moreover the exacerbation of ethnic conflict in Europe is not limited to the Eastern fringe, the states formerly part of the Communist world. Nor is the new European violence primarily localized in the zones of economic meltdown, such as Greece and Spain. On the contrary, race and violence are more notorious in the central welfare states of the European Union—Scandinavia, France, and Germany.

On July 22, 2011, Norwegian Anders Behring Breivik took the lives of seventy-seven victims, first detonating a car bomb in Oslo’s government district and then going on a shooting spree on nearby Utoya Island. His internet postings displayed an ideological extremism full of hostility toward Muslim immigrants and driven by a vision of mortal combat between Islam and the West.

In the wake of the slaughter, some public figures tried to use Breivik’s crimes to score political points by blaming the violence on anyone who had raised questions about Europe’s failed integration policies. The tragedy of Utoya sadly became a convenient tool for the left to attack conservative political opponents. Breivik’s trial is now underway. If he is found guilt, he faces a maximum sentence of twenty-one years; there is no death penalty in Norway. In the meantime, he has begun to use the trial as an opportunity to broadcast his extremist message. It is likely that the court will eventually declare him insane in order to defuse the explosive politics of the case.

Europe's simmering ethnic conflicts are most pronounced in the central welfare states.

Breivik’s crimes and extraordinary brutality represent, in an extreme version, the simmering ethnic and racial conflicts in Europe—perhaps especially in Northern Europe. Once renowned for tolerance and liberalism, the North has witnessed acts of gross intolerance, especially around issues of immigration, both on the part of immigrants as well as locals.

The assassination of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh on November 2, 2004 by Mohammed Bouyeri took place by day in the streets of Amsterdam. Born in Holland of Moroccan parents, Bouyeri left a note, pinned to van Gogh’s corpse with a knife, attacking him for a film critical of Islam’s treatment of women. The note included threats to Jews, the West, and individual politicians, including the then-Interior Minister of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, who became the President of France in 2007.

Less than a year after the van Gogh killing, in September 2005, the Danish magazine Jyllands-Posten published a set of Mohammed caricatures, which set off violent protests worldwide. An extensive debate ensued over freedom of the press and its relation to religion, in some ways a reprise of the controversy around Salman Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses (1988). Yet in these more recent conflicts—the van Gogh assassination, the Mohammed cartoons, and the Breivik killings—something very ugly and ominous is coming to the fore: the breakdown of contemporary societies along racial lines, undermining democratic norms.

Two Danish writers provide a compelling explanation of this worrisome development in their book that has recently appeared in English translation, The Democratic Contradictions of Multiculturalism. Authors Jens-Martin Eriksen and Frederik Stjernfelt take a hard look at the consequences of defining people in terms of cultural communities and then giving those cultural identities priority over the expectations of equality before the law. Multiculturalism in Europe emphasizes group rights over individual rights, thereby undermining the tradition of political liberalism in the name of protecting collective cultural traditions.

European policies facilitate the segregation of immigrant populations.

Eriksen and Stjernfelt trace the history of the idea of “culturalism.” It began with particular schools of anthropology, eventually influenced policies by the United Nations, and led to divisive consequences for contemporary Europe. They suggest that current policies facilitate the segregation of immigrant populations. As a result, immigrant ghettos can incubate radicalism among disaffected youth, like Bouyeri, while the structural separation of majority and minority populations feeds the potential for populist resentment or even violent extremism, such as Breivik’s. Consider two recent cases in Germany and France.

In November 2011, German Special Forces broke up a right-wing extremist gang, the so-called Zwickau Group of the “National Socialist Underground,” accused of carrying out a series of murders that had targeted immigrants from Turkey and Greece. The group had emerged from the small but active neo-Nazi community in Germany. With the police hot on their trail in the wake of a bank robbery, two group members shot themselves, and a third surrendered to authorities; the conspiratorial network began to unravel.

Now turn to France, On March 23, 2012 in Toulouse, twenty-three-year old Mohammed Merah entered a Jewish school and murdered three children and a rabbi, point blank. During the previous week, he had killed three off-duty French soldiers. After the school killings, he fled to an apartment where police tracked him down.

During a thirty-one-hour siege, Merah explained that he had committed the murders as protests over the plight of the Palestinians, the French participation in the Afghanistan War, and the policy of banning Muslim headscarves in public schools. Although police hoped to capture him alive to explore his claims of connections to al-Qaeda and to put him on trial, when they stormed the apartment, he returned fire before jumping through a window to his death.

In terms of explicit ideology, the neo-Nazi Zwickau Group and the Islamist extremist Merah have little in common. The former waged a war against immigrants, while Merah grew up in an immigrant household, although he was himself born in France. Yet both chose to pursue paths of violence against opponents defined in racial terms, and both shared anti-Semitic views.

European societies have not been able to negotiate relations between majority and minority communities successfully. On the contrary, persistent high unemployment, the welfare state, and festering animosities have contributed to the potential for violent explosions such as those in Zwickau and Toulouse.

Multiculturalism in Europe undermines the tradition of political liberalism.

Given this backdrop, it is not surprising to find public fears about violence and race playing a role in general elections. The events in Toulouse have given the topics of security and terrorism greater importance in the French presidential campaign, and this has given Sarkozy a late boost for reelection this spring. He had been previously trailing his main opponent, the Socialist Francois Hollande, in the polls, but his public response to Toulouse has amplified his claim to be stronger on security. His opponents, in turn, have accused him of orchestrating the recent arrests of alleged Islamist conspirators solely out of electoral motives. It remains to be seen if Sarkozy’s enhanced security profile will be sufficient for him to overcome Hollande’s lead.

The next national election in Germany will not take place until the autumn of 2013, but important regional elections are scheduled earlier, and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) is chomping at the bit to unseat Chancellor Angela Merkel. It appears that it may be borrowing a nasty tactic from British Labour, fishing for votes with anti-Semitic bait. In March, SPD chair Sigmar Gabriel chose to utilize far-left rhetoric in speaking about Israel’s “apartheid” policies, a tactic that will likely win his party votes on both ends of the German spectrum, and probably not only on the ends. Merkel has expressed strong support for Israel, so the SPD has chosen to stake out an alternative position. Such are German politics.

To hammer home that point, SPD cultural icon and Nobel Prize–winning author Günter Grass recently published a poem in major newspapers, denouncing Israel for planning to attack Iran—curiously enough, without mentioning Iranian threats to eliminate Israel. In the robust discussion that has ensued in Germany, nearly no one has defended the poem on literary grounds; it is widely recognized as just a political statement.

Yet, while Grass has faced trenchant criticism for his analysis of Near East politics and for his dabbling in anti-Semitism, he has also found more than a few supporters. The affair is therefore more than a debate about a poem. Grass has played a role in German political life for decades. He campaigned for the SPD in 1969 and contributed to Willi Brandt’s victory, a turning point in post-war German history. Grass may be targeting a rerun of that victory, using German support for Israel as a wedge issue to appeal to anti-Semitic voters. The SPD is not so ideologically pure as to turn down this gift horse, if it’s a way to ride to a victory on election night. SPD chair Gabriel has, in any case, explicitly defended Grass; he knows where to find the votes.

Contemporary Europe is riven by ethnic tensions and is fragmenting along multicultural lines. On the extremes, tragic violence is becoming familiar: Amsterdam, Utoya, Zwickau, Toulouse—and in the background, there is the “home-grown” terrorism of the bombings in London and Madrid. It is no wonder then that voters are looking for candidates who promise effective security measures and counter-terrorism policies. At the same time, however, candidates face the temptation to pursue electoral strategies that identify scapegoats for vilification: race and violence, the European way.