- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

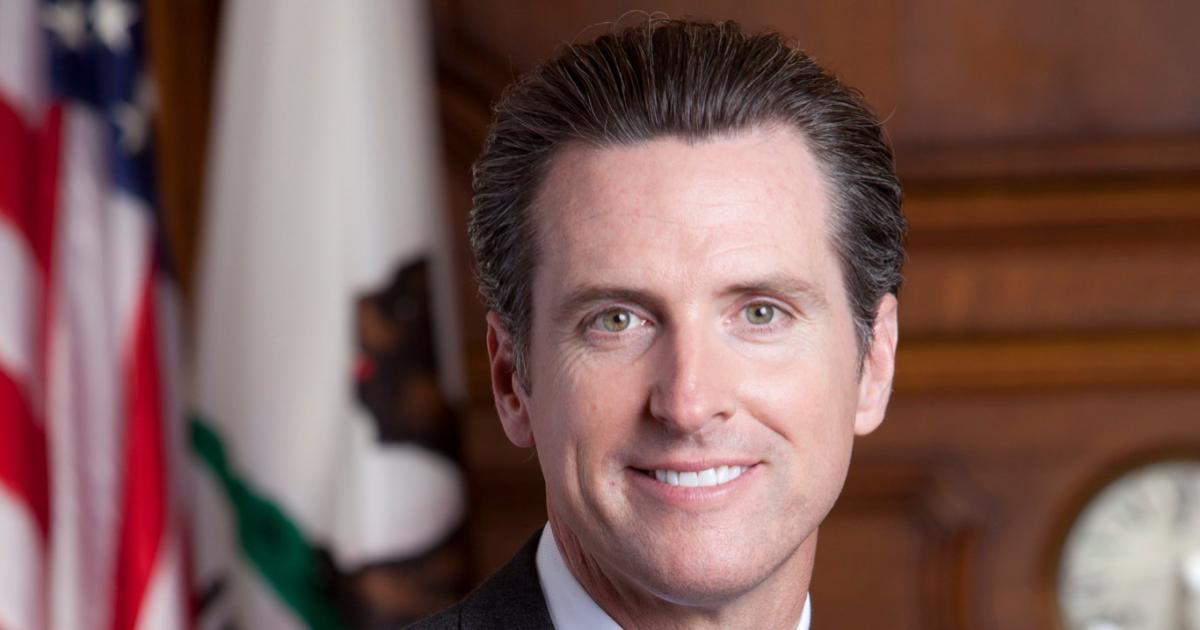

I have plenty of policy quarrels with Gavin Newsom.

To name a few, I desperately wish that California’s governor would support more water storage, lower taxes, remove regulatory burdens, stop undermining Proposition 13, and cease trying to dismantle public charter schools.

I have a conservative voting record on each one of these issues. However, Newsom campaigned for governor back in 2018 with policy prescriptions quite different from my own on these matters, and he won the election by a landslide. He’s scheduled to stand for reelection next year, beginning with the state’s June top-two primary.

Yet, through a recall law with a low bar to qualify, a court judgment in early November of last year extending the time to collect signatures by four months to account for the pandemic, and a confluence of natural disaster and deadly disease, California voters may recall a governor in his third year in office with a primary and general election just months away. (In 2003, then governor Gray Davis was recalled by California voters with three years remaining in his second term in office.)

To what end? It’s a fair question.

A frustrated GOP electorate clings to a false hope that a positive outcome in the recall election might reboot its political competitiveness in an otherwise solidly blue state. (Dating back to 2000, Republicans have lost fifty-one of fifty-two statewide contests that did not include Arnold Schwarzenegger.)

However, the circumstances surrounding this recall and the one in 2003 couldn’t be starker. Not only did Schwarzenegger come to office three years before he’d stand before the electorate again, he also had a chance to assemble a remarkable cast of public servants (many of whom I know and deeply admire). In other words, Schwarzenegger had time to establish a credible record and, as a result, cruised to election in his own right, in 2006, as a credible Republican.

In contrast, the leading GOP replacement candidate in this year’s recall election would take on the job mere months before next year’s gubernatorial primary. The ability to staff the governor’s office, confirm appointees, and accomplish lasting policy change will be largely out of reach.

It’s my belief that there’s not enough time to do any one of these tasks right. Moreover, a near-certain crushing defeat in 2022 by another just-as-liberal Democrat will have done little to advance fiscally conservative ideas or to push California back to the political center for future elections. Given its stained brand after four years of a chaotic presidency, California’s Republican Party would be better advised to spend its time and treasure developing a message that might actually attract a majority of voters—a platform of compelling ideas, not a French Laundry list of grievances.

Confidence in government erodes when we give people false hope. A recall that simply lists conservative policy gripes that likely wouldn’t attract more than 40 percent of the electorate in a more conventional California statewide election is a bad idea. But here we are. Ironically, if the governor were to be recalled, it won’t be because of the issues listed in the petition to do so—immigration, taxes, saving Proposition 13, addressing homelessness, or the death penalty, to name most (all reasonable reasons to support or not support a political candidate in a regular election).

Instead, Newsom might be recalled because of events beyond any California governor’s full control—searing fires, deadly drought, and an unnerving pandemic have made for a surly electorate. It can be argued that Newsom has not competently tackled these issues, but such criticism is no more than partisan disagreement with his policies near the end of his term.

A successful recall might also set back the advance of center-right ideas. Every attempt to advance legislative policy will be met with sure defeat. Opaque legislative rules will bury any intended coherent message. Meanwhile, every past statement—fair or not—made by the leading replacement candidate will be aired repetitively. The key to effective political persuasion is to give your audience permission to hear you out. A recall installing a candidate long on rhetoric and controversial statements but short on competent policy or management expertise—instantly thrust into a statewide general election race—is risky at best.

Finally, a gubernatorial candidacy that just received far fewer votes than those wishing to keep Newsom in office for a final year will energize a revengeful Democratic base that could upend the prospects of GOP candidates in swing legislative districts next year. Losing the governorship and coming up short in congressional and legislative races in the fall of 2022 would be seen as a setback for common-sense center-right ideas and reveal the recall as foolish.

While the rules allow for a recall, we should be prudent in its application. Imagine if California’s recall law were in place in Florida or Texas. Both Republican governors in those states, likewise facing reelection and saddled with lower approval ratings amid COVID-19 surges, could be facing recall as well. Such a law applied to all states, with such a low barrier of entry to qualify, would be a recipe for chaos, giving a small slice of the electorate too much power to interfere with governing.

Those with more conservative leanings should desire stable governments, not perpetually unstable political landscapes. Further, here in California, the recall is a mismanagement of our tax dollars, estimated to cost nearly $276 million in the year before a regular election: fiscal folly. At the very least, we need to reform the recall process in California to make it more difficult to qualify and bar recall if more than half a term is completed.

What we need more of in America is competent government, not more of it. Republicans in California have long stood for competent government. Governors Ronald Reagan, George Deukmejian, Pete Wilson, and Arnold Schwarzenegger were all highly competent and represented a vision in their respective eras that rallied a majority of Californians to their candidacy. All were leaders with deep experience in government or were highly successful in their industries.

Ask yourself: How many of the recall candidates clear that bar?

Jim Cunneen served as a Republican assemblyman from 1994 to 2000, representing Silicon Valley in California’s legislature. He is now a member of the California Common Sense Party.