- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Economics

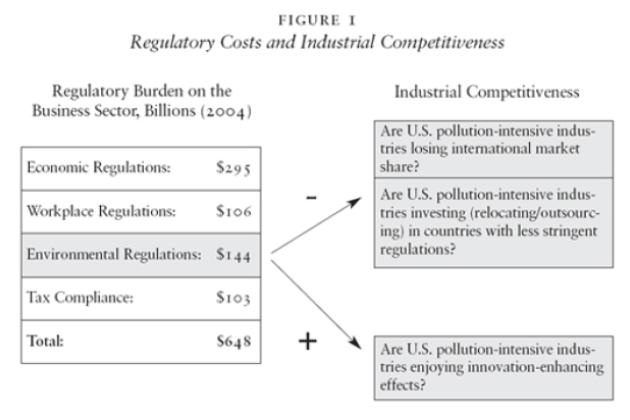

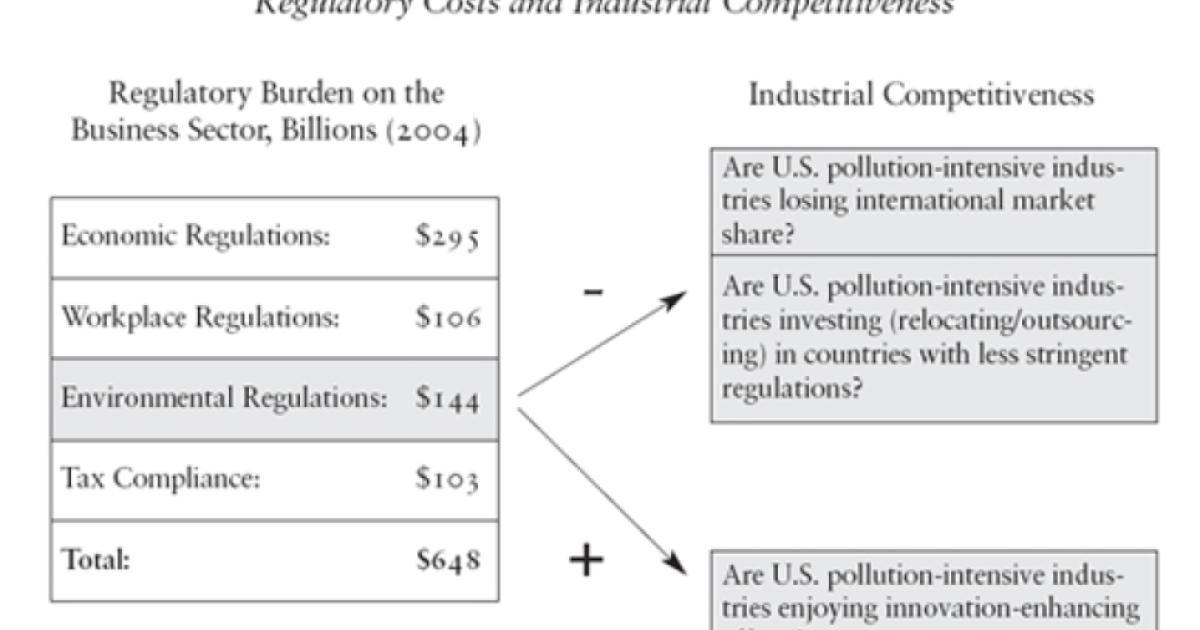

What is the cost to U.S. businesses of complying with federal regulations? In 2004, U.S. federal government regulation cost businesses in the United States an estimated $648 billion.1 This cost burden has increased about 19 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars since 2000. Notwithstanding the many benefits to society of federal regulations, several indicators show that the cost for businesses of complying with these regulations is sizable and has been growing rapidly.

Melinda Warren, director of the Weidenbaum Center Forum, notes that “expenditures of federal regulatory agencies and the trends in this regulatory spending over time . . . are a proxy for the size and growth in regulations with which American businesses, workers, and consumers must comply.”2 A study by Susan Dudley and Melinda Warren reports that spending by federal regulatory agencies on regulatory activity reached $37 billion in fiscal year 2004.3 This cost has grown 36 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars since 2000. Total staffing in federal regulatory agencies in fiscal year 2004 equaled 239,624 fulltime equivalent employees; it grew by 38 percent between 2000 and 2004.

More than two decades ago, President Reagan made regulatory relief (deregulation as well as slowing the growth of new regulations) one of his four pillars of economic growth. Reducing the paperwork burden required by federal regulations became essential to the process. He specifically used the term regulatory relief rather than regulatory reform to emphasize his desire to cut back regulations, not just make them more effective. In line with this idea, he created the Competitiveness Policy Council in 1988 to advise the president and Congress on policies to promote U.S. competitiveness.

The cpc recommended a federal law calling for the executive branch to attach a Competitiveness Impact Statement (cis) to any new legislative proposal to Congress that might affect U.S. competitiveness. A cis would require all U.S. federal government agencies to produce a document describing how major proposed federal laws significantly affect the competitiveness of companies operating in the United States. The cpc ceased operation in 1997 when Congress stopped funding it, and the recommendation for a cis was never approved.

The concern has recently arisen that the United States is losing its position as a global leader. Bernard Schwartz from the Brookings Institution notes that “rising economies like China and India represent new challenges to our position on the playing field as they introduce millions of new workers into the labor market, millions of dollars of investment into scientific programs which prior to this have been an area where the Western nations had a more important role to play.”4 Tom Donohue, President and ceo of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, acknowledges the delicate balance between regulation and competitiveness: “Let’s not overlook the importance of government regulation. Smarter regulation can strengthen America’s economic competitiveness and status as a global leader — excessive regulation can cause us to fall behind competition.”5 A timely issue is, then, whether U.S. federal regulation is smart or excessive.

Regulation strangling competitiveness?

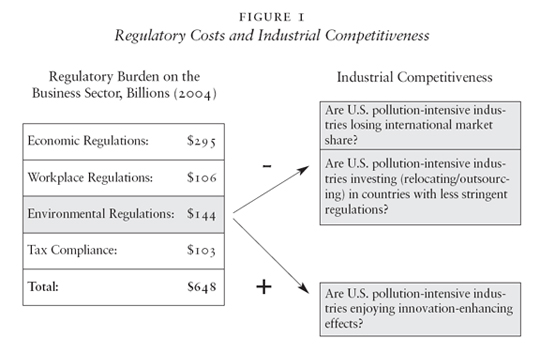

Figure 16presents estimates of the costs to business of federal regulations by type: economic, workplace, environmental, and tax compliance. Economic regulations — those that refer to government-imposed restrictions on the decisions a firm makes regarding price, quantity, entry, and exit — cost businesses $295 billion in 2004. This category also includes international trade and investment regulations that impose restrictions on foreign imports (e.g., quotas and tariffs). Social regulations cost businesses $250 billion in 2004. These are regulations that protect the public interest in the workplace (wages, benefits, safety, and health) and in the environment (e.g., water and air pollution). Finally, there is a substantial burden on U.S. businesses for costs associated with the time and resources required for recordkeeping, reporting, and compliance with laws and regulations. The time required to comply with the federal tax code accounts for a large part of this burden ($103 billion in 2004). A key question: Do federal regulations (measured, for example, by the regulatory cost burden) affect the competitiveness of U.S. industries?

A review of the literature on the relationship between federal regulation and the international competitiveness of U.S. industries shows two trends (both summarized in Figure 1). First, most studies focus on the effect of environmental regulations because only these data are available at the industry level. Second, there are two opposite views on the environmental regulation’s effects on competitiveness. The conventional view associates environmental regulation with negative effects for pollution-intensive industries, maintaining that regulations translate to increasing costs for such industries, putting them at a competitive disadvantage. This view argues that these industries would lose market share or would relocate to countries with less stringent environmental regulations (pollution havens). In contrast, the revisionist view makes a case for the positive aspects of environmental regulations on these industries, especially the beneficial effects on innovation and export opportunities in the market for green technologies.

Several empirical studies show little propensity for pollution-intensive industries to move to pollution havens.7 This is because even in industries with high pollution-control costs, companies often face other deterrents to relocation, including fixed capital costs and sensitivity to transportation expenses.8 What is more, even in cases where pollution-intensive industries have relocated to countries with less stringent environmental regulations, it is not clear that less regulation was the main incentive for them to relocate there. Jonathan Barton and his colleagues analyzed in 2007 the location patterns of three pollution-intensive industries and concluded that these firms’ investments in developing countries have been motivated mainly by a desire to participate in rapidly growing markets or to gain access to raw materials.9 Indeed, Adam Jaffe and his coauthors concluded in a literature review that differences across countries in environmental compliance costs rarely have a serious effect on industrial competitiveness.10

Michael Porter hypothesized in 1991 that properly designed environmental standards can prompt innovation that may partially or more than fully offset the cost of complying with them.11 Such innovation offsets can not only lower the net cost of meeting environmental regulations, but can even lead to absolute advantages over firms in foreign countries that are not subject to similar regulations. By stimulating innovation, strict environmental regulations can actually enhance competitiveness. There is considerable disagreement, however, over the extent to which innovation offsets exist in practice.12 When they do exist, there is also controversy over whether they are sufficiently large, relative to research and development (r&d) and management costs, to give rise to true win-win situations.

The issue of whether regulatory policy hinders the international competitiveness of U.S. firms has stimulated a heated debate in the United States.13 The debate, however, is limited to results from studies that analyze either the costs or benefits associated with environmental regulations, but rarely both (the net effect). Moreover, this discussion focuses only on the effect of environmental regulations because there is a lack of data on the cost for industries to comply with other kinds of federal regulations, such as health and safety laws or economic regulations. This lack of data may explain the relatively smaller number of studies addressing the cost for industries of complying with regulations other than environmental ones. Why is the U.S. government not collecting data that will allow an understanding of the effects of all regulations on the competitiveness of U.S. industries?

The regulatory analysis process

During the nixon administration, new regulatory agencies in charge of social regulation — health, environment, and safety — were established. However, their creation was not accompanied by an effort to accurately measure the costs and benefits to society of the new regulations emerging from them. When the new regulatory agencies were created, there was no executive branch oversight, so routine regulatory actions seldom received congressional scrutiny.14 It was not until the 1980s that it became apparent that some oversight mechanism was needed to ensure that these regulations were in society’s best interest, and that the costs and benefits of major new regulations needed to be estimated.15

Early analyses of the impact of regulation on society were dominated by techno-bureaucratic thinking, meaning that analysts made little use of the tools from neoclassical economics. In his book Reinventing Rationality: The Role of Regulatory Analysis in the Federal Bureaucracy, Thomas O. McGarity, who introduced the term “techno-bureaucratic thinking,” describes it as follows:

The solution to regulatory problems under the traditional model depends heavily upon professional judgment. Because the existing data rarely compel a particular result, a lot of techno-bureaucratic thinking is really grounded in a kind of intuition that is informed by technical training and experience. The technical experts do not analyze the problem and derive a solution so much as they “feel” their way through to an answer, accommodating as many affected interests as possible along the way to reduce the external resistance to their ultimate resolution of the problem. . . . It is a matter of secondary importance that the benefits of the rule can somehow be shown to exceed its costs.16

The informality that permeated the regulatory system created general dissatisfaction with the regulatory process among those being regulated. In 1974, to introduce some presidential control over regulatory policy, President Ford issued Executive Order 11281, which mandated that an Inflation Impact Statement accompany all major proposals for legislation, rules, and regulations. Responsibility for implementing the new program was delegated to a new agency, the Council on Wage and Price Stability within the omb. The analysts at cwps quickly concluded that a regulation would not be truly inflationary unless its costs to society exceeded the benefits it produced. Moreover, they defended the idea that the inflationary impact of a proposed rule could best be ascertained by quantitatively comparing the costs and benefits of the proposed rule to the costs and benefits of its alternative.17

During the Ford and the Carter administrations, regulatory analysis focused on improving the tools with which the effectiveness of a regulation was evaluated. McGarity’s book describes this process as one of change from techno-bureaucratic thinking to comprehensive analytical rationality, which depends heavily on the paradigms of neoclassical microeconomics. In this latter model, the analyst would need to evaluate the aggregate costs and benefits to society of a new regulation but not necessarily its effects on different groups within society (including businesses).

President Reagan believed that regulations and excessive paperwork placed businesses at a disadvantage in an increasingly competitive world marketplace. He supported continued deregulation and other reforms to eliminate regulatory obstacles to open competition. Shortly after taking office, Reagan abolished the cwps and shifted its regulatory review staff to a new Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within the omb. This group was put in charge of estimating the aggregate social costs and benefits of new regulations. oira would evaluate new regulations based on two questions: Are the benefits of the proposed regulation larger than its costs? And is the proposed action the best one among alternatives?

Under President George H.W. Bush, regulatory oversight procedures remained virtually unchanged. Later, President Clinton introduced Executive Order 12866, which limited oira’s reviews to “significant regulations” — those with a likely substantial effect on the economy, the environment, or public health and safety, or those raising novel policy issues.18 This executive order emphasized that many consequences of policies are difficult to quantify and that qualitative concerns should be taken into account as well. It introduced only a slight modification to Reagan’s order by streamlining the process (so that the omb reviewed only 500 regulations per year instead of 2,200) and by increasing its public consultation and transparency requirements.19

On January 18, 2007, President George W. Bush issued two documents. The first was Executive Order 13422, which amended Executive Order 12866 and required that each federal agency have a regulatory policy office run by a political appointee to supervise the development of rules and papers providing guidance to regulated industries. The other document, omb’s final bulletin on “Agency Good Guidance Practices,” extends oira review to include significant guidance documents. Federal agencies are increasingly using guidance documents to inform the public and to provide direction to their staff regarding agency policy on the interpretation or enforcement of their regulations. According to testimony before a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee by Robert W. Hahn and Robert E. Litan in April of 2007, no one knows the real impact of guidance documents, but it could be substantial.20

The U.S. regulatory program has become more sophisticated over time. U.S. regulatory agencies now use tools from neoclassical economics to measure the costs and benefits of new regulations to society. This is a step forward from the techno-bureaucratic thinking that dominated earlier regulatory analysis; however, questions remain about how successful regulatory agencies are in measuring the costs and benefits of new regulations.

Executive Order 12291issued in 1981 required, among other things, that all major regulations (over $100 million annual impact) be accompanied by a Regulatory Impact Analysis. Robert W. Hahn and Patrick M. Dudley analyzed in 2007 how well the U.S. government conducts cost-benefit analyses after more than 25 years of preparing rias.21 The authors assessed a sample of 75 cost-benefit analyses of federal environmental regulations from the epa that spanned the Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Clinton administrations. They found that a significant percentage of the analyses done by the epa did not report some very basic economic information and that there was a great deal of variation in the quality of the cost-benefit analyses. They point out that while 100 percent of the rias monetized at least some costs, only 50 percent monetized at least some benefits. This suggests that comparisons of costs and benefits were not occurring in a large number of cases for which the necessary data were actually available. Another 2007 study, this by Robert W. Hahn and Paul C. Tetlock, further concludes that basic questions like whether cost-benefit analyses tend to overstate costs or whether they tend to overstate benefits still remain unanswered.22

The evidence shows that the government is still very inefficient in measuring the costs and benefits of regulations, and more importantly, that it has put little effort in measuring the effects of federal regulations among different industries. There has been some emphasis on measuring the impact of regulations on small businesses, but for the most part, data are still lacking that would allow evaluating the impact of regulation on the competitiveness of U.S. industries separately from its effects on households and other groups. This is not surprising as distributional concerns, while important, have not been a primary focus of cost-benefit analyses.23 Is there a better way?

Learning from Europe

The ria has a counterpart in Europe: the Impact Assessment. An ia is required for any major European Commission initiative and contains an evaluation of the social, economic, and environmental impacts of various policy options associated with a proposal. The ec encourages estimates to be expressed in qualitative, quantitative, and, where appropriate, monetary terms.24 by Andrea Renda of the Center for European Policy Studies analyzes the first 70 ias carried out by the ec from 2003 to 2005 using a scorecard.25 Renda found that the ias seldom estimated costs, almost never quantified costs to businesses, did not specify benefits, and virtually never compared costs and benefits. In addition, alternatives were seldom compared and discount rates were almost never specified. Given the difficulty of estimating a new regulation’s costs and benefits by using neoclassical microeconomic methods, both the ec and the European Union’s business community have opted for a complementary methodology — business surveys — to estimate how new regulations will affect the competitiveness of European businesses.

In the past few years, about 20 member countries as well as the eu’s own institutions have been working to reduce companies’ administrative costs due to regulation. This objective is part of a general policy among decision-makers that business-friendly regulation is a priority in marketing the eu countries as the best place to do business. In line with this policy, the ec established a high-level group of independent stakeholders in 2008. The group has a three-year mandate to advise the ec through the implementation of its “Action Plan on Reducing Burdens Imposed by Legislation in the eu.” The group has 15 members from industry, small and medium enterprises, and environmental and consumer groups. Although the focus of the group has been on reducing administrative burdens by 25 percent, the January 2008 nnr Newsletter suggests that it “must look beyond administrative costs. Considerations should be given to the total costs to businesses of complying with regulation, including policy and enforcement costs.” The success of these institutions and groups relies heavily on information collected from questionnaires sent to businesses.

One of the most important business initiatives developed by the ec is the European Business Test Panel established in 2003. The ebtp is composed of a representative sample of 3,600 firms across sectors and countries that comprise the European economy. By joining the ebtp, companies have an opportunity to remark on upcoming eu legislation and on the impact of major regulations. Companies are invited to comment on upcoming policy proposals between six and eight times per year through a short online questionnaire. The ec has a “10 questions in 10 minutes” policy and intends to provide helpful feedback on the results obtained. The ec anticipates that the ebtp could be incorporated into ias in the future.

Among the eu member countries, the business community in Sweden has undertaken one of the most important initiatives (it is also one of the oldest along these lines). The Board of Swedish Industry and Commerce for Better Regulation (known as the nnr) was founded in 1982 as an independent, nonpartisan organization funded entirely by its members. The membership consists of the 14 largest Swedish business organizations and trade associations, comprising a combined membership that represents a third of all active companies in Sweden. One of its principal tasks is to coordinate the business sector’s scrutiny of ias and to negotiate with regulatory agencies during the evaluation of the costs and benefits of a new regulation.

The nnr chairs the Better Regulation Working Group of the Confederation of European Business. The Group includes representatives from all major business organizations in the eu member countries. It encourages a Europe-wide competitive industrial policy and acts as a spokesperson for European institutions. Its recommendations are communicated to eu< policymakers to make sure that business interests are taken into account as legislation is formulated. Similar to the case of the eu as a whole, the success of Sweden’s business organizations is tied to good reports and data produced from responses to questionnaires sent to businesses. We will highlight some of the most recent reports in the following paragraphs.

In November 2007, nnr published its sixth annual report titled “The nnr Regulation Indicator for 2007: An Evaluation of the Swedish Government’s Progress Towards Better Regulation.” The report analyzes the quality of new and amended regulations and the progress of the government’s Better Regulation program. The 2007 evaluation covers 150 proposals for new or amended regulations put forward by government agencies and departments. The report shows that in over 60 percent of the cases, proposed new or amended regulations would lead to an increase in administrative costs for businesses. nnr proposes 12 measures that the government should implement to reduce businesses’ administrative costs of complying with regulation by 25 percent by 2010.

In addition to the annual report, the nnr published in December of 2007 a study titled “The Total Cost of Regulations to Businesses in Sweden.” This study summarizes findings from a project to estimate the total cost to businesses of complying with selected new regulations. The costs were divided into three categories: administrative, financial, and material or policy costs. In-depth interviews were conducted with companies from different sectors and of different sizes to estimate their total annual compliance costs that stem from national and eu regulations.

Perhaps the nnr’s biggest success is a government ordinance approved on January 1, 2008, requiring Swedish regulatory agencies to carry out ias when proposing new national regulations or amending existing ones. The ordinance states that policymakers should consult with businesses and take into consideration all effects on businesses, not just monetary costs. The nnr was also successful in conveying to the Swedish government the need for a national Impact Assessment Board that will review the quality of all ias.

The proactive attitude of the business community in Europe has led to successful policy initiatives. This strategy is based on two components. First, instead of waiting for the federal government to produce the appropriate data, the business community in Europe has been building its own data through questionnaires and interviews. Second, it has created appropriate organizations that use these data to document the effect of regulation on their competitiveness. The U.S. business community should follow the same path.

A competitive impact statement?

In 2004, the costs of federal regulation reached $1.1 trillion for all groups in society (including businesses, consumers, and state governments). More important for the focus of this article, the total cost of regulation for U.S. businesses was $648< billion, and the cost per employee was $5,633, a 4.1 percent increase since 2000 (after adjusting for inflation). The burden of total regulatory costs was even larger for the manufacturing sector, which in 2004 bore a cost per firm of $548,077 and a cost per employee of $10,175. Should businesses revisit the idea of a Competitiveness Impact Statement that will force federal agencies to account for the effects of regulation on businesses?

The effectiveness of a new policy, such as a cis, dedicated to measuring the effects of new regulations on U.S. businesses requires obtaining good data on the cost of regulations at the industry and firm level.26 Instead of waiting for the federal government to produce the appropriate data, the U.S. business community could follow the European strategy and produce relevant data themselves. This approach still leaves us with a puzzle: Which U.S. organization could mimic the European model by conducting similar surveys and relevant studies?

Two organizations are good candidates. The Council on Competitiveness, founded in 1986, is a group of corporate ceos, university presidents, and labor leaders committed to enhancing U.S. industrial competitiveness in the global economy.27 A nonpartisan, nongovernmental organization in Washington, D.C., the Council shapes the debate on competitiveness. Competitiveness, however, is a broad concept that involves a diversity of issues. For instance, in 2008, the Council’s focus has been on the need to improve the education system in the United States, to set a national agenda to equip Americans with the skills needed to compete globally, and to identify the barriers that large and small firms face in moving from desktop computers to high performance computing servers. Thus, it appears that examining the effect of federal regulation on industrial competitiveness might not be the Council on Competitiveness’s immediate priority. Another candidate is the aei Reg-Markets Center (formerly the aei-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies) at the Brookings Institution. The Center studies how markets, laws, and regulation contribute to economic well-being.

Altogether, the justification for a cis or a similar new approach would have to be based on an analysis of the effects on business of all regulatory costs (not just pollution abatement costs) and on a deeper understanding of the strategies that companies follow to offset stricter regulatory policies. However, U.S. businesses should not simply wait for the federal government to build the necessary databases and studies that will support such initiatives. Rather, they should emulate the experience of European countries by conducting their own surveys and studies on the effect of major regulations on the competitiveness of businesses and strengthen the organization that will produce these data. The link between regulatory costs and industrial competitiveness deserves serious attention, especially through the building of new data sources and the surveying of U.S. businesses on the effects of major regulations.

1 W. Mark Crain, “The Impact of Regulatory Costs on Small Firms,” (sba Office of Advocacy, 2005), available at http://www.sba.gov/advo/research/rs264tot.pdf (this and all subsequent on-line references accessed May 5, 2009).

2 Quoted in “Bush Administration Regulatory Spending Outpaces Inflation, Study Finds,” News Tips (July 16, 2004), available at http://news-info.wustl.edu/tips/page/normal/906.html.

3 Susan E. Dudley and Melinda Warren, “Regulators’ Budget Continues to Rise: An Analysis of the U.S. Budget for Fiscal Years 2004 and 2005” (Mercatus Center and Weidenbaum Center, 2004).

4 From “The Future of U.S. Competitiveness: Is America Investing Enough in Science and Technology to Compete?” (Brookings Institution event, October 5, 2006), transcript available at http://www.brookings.edu/events/2006/1005global-economics.aspx.

5 Tom Donohue, “Smarter Regulation for a Stronger America,” U.S. Chamber Magazine< (2009).

6 From Crain, “The Impact of Regulatory Costs on Small Firms.

7 “Report on the Furniture Finishing Industry” (U.S. gao, 1990); Joseph P. Kalt, “The Impact of Domestic Environmental Regulatory Policies on U.S. International Competitiveness,” in Michael A. Spence and Hather A. Hazard, eds., International Competitiveness (Harper and Row, 1988); Patrick Low and Alexander Yeats, “Do ‘Dirty’ Industries Migrate?,” in Patrick Low, ed., International Trade and the Environment (World Bank, 1992); James A. Tobey, “The Effects of Domestic Environmental Policies on Patterns of World Trade: An Empirical Test,” Kyklos43:2(1990).

8 “Gene Grossman and Alan B. Krueger, “Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement,” in Peter M. Garber, ed., The Mexico-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (mit Press, 1993).

9 “Jonathan Barton, Rhys Jenkins, Anthony Bartzokas, Jan Hesselberg, and Hege Knutsen, “Environmental Regulation and Industrial Competitiveness in Pollution-Intensive Industries,” in Seed Parto and Brent Herbert-Copley, eds., Industrial Innovation and Environmental Regulation: Developing Workable Solutions (United Nations University Press, 2007), available at http://www.idrc.ca/en/ev-105261-201-1-do_topic.html.

10 Adam B. Jaffe, Steven R. Peterson, Paul R. Portney, and Robert N. Stavins, “Environmental Regulation and the Competitiveness of U.S. Manufacturing: What Does the Evidence Tell Us?” Journal of Economic Literature 33:1 (1995); Adam B. Jaffe and Karen Palmer, “Environmental Regulation and Innovation: Panel Data Study,” (National Bureau of Economic Research, 1996), available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w5545.

11 Michael E. Porter, “America’s Green Strategy,” Scientific American264:4 (1991).

12 “Environmental Regulation and the Competitiveness of U.S. Manufacturing: What Does the Evidence Tell Us?”

13 Richard B. Stewart, “Environmental Regulation and International Competitiveness,” Yale Law Journal 102:8 (1993).

14 Kip W. Viscusi, Joseph E. Harrington, and John M. Vernon, Economics of Regulation and Antitrust, 4th edition, (mit Press, 2005).

15 Economics of Regulation and Antitrust, 4th edition.

16 Thomas O. McGarity, Reinventing Rationality: The Role of Regulatory Analysis in the Federal Bureaucracy (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 7.

17 Reinventing Rationality: The Role of Regulatory Analysis in the Federal Bureaucracy.

18 Sally Katzen, David Vladick, Rick Melberth, and Bill Kovacs, “Amending Executive Order 12866: Good Governance or Regulatory Usurpation?,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight, Committee on Science and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives (February 2007), available at http://science.house.gov/publications/hearings_markups_details.aspx?NewsID=1269.

19 John F. Morrall, “Regulatory Impact Analysis: Efficiency, Accountability, and Transparency,” (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2001).

20 Robert W. Hahn and Robert E. Litan, “Evaluating the New Executive Order on Regulation,” testimony before the House Investigation and Oversight Subcommittee, Science and Technology Committee, U.S. House of Representatives (April 2007), available at http://www.brookings.edu/testimony/2007/04governance_hahn.aspx?rssid=hahnr.

21 Robert W. Hahn and Patrick M. Dudley, “How Well Does the U.S. Government Do Benefit-Cost Analysis?,” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy1:2 (2007).

22 Robert W. Hahn and Paul C. Tetlock, “Has Economic Analysis Improved Regulatory Decisions?” (aei-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies, April 2007), available at http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=982233.

23 Hahn and Tetlock “Has Economic Analysis Improved Regulatory Decisions?”

24 “The Effects of Environmental Policy on European Business and its Competitiveness: A Framework for Analysis” (Commission of the European Communities [cec], October 2004), available at http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/enterprise_policy/industry/doc/sec_769_2004.pdf.

25 Andrea Renda, Impact Assessment in the EU: The State of the Art and the Art of the State (Center for European Policy Studies, 2006).

26 We interviewed three professors at the University of Texas at Austin, Thomas O. McGarity, David B. Spence, and Frank B. Cross, who each have expertise on U.S. regulatory policy, to test their support for acis. They agreed on the need to get better data but also stressed the importance to study whether a cis will intensify the paperwork burden of federal agencies.

27 Most of the information about the Council comes from its website: http://www.compete.org.