- Economics

- Law & Policy

Few at that time could have foreseen the outlines of what exists today. Many former communist countries, in the intervening years, experienced a rebirth of freedom, but Russia came to be dominated by poverty, intimidation, and crime.

The reason is that, during the reform period, which witnessed a massive effort to remake Russian society and the Russian economy, Russia once again fell victim to a false idea.

The victory over communism was a moral victory. Millions took to the streets not because of shortages but in protest over communism’s attempt to falsify history and change human nature. As a new state began to be built, however, all attention shifted to the building of capitalism and, in particular, to the creation of a group of wealthy private owners whose control over the means of production, it was assumed, would lead automatically to a free market economy and a law-based democracy.

This approach, dubious under the best of conditions, could not but be disastrous in the case of Russia. It meant that, in a country with a need for moral values after more than seven decades of spiritual degradation under communism, the introduction of capitalism came to be seen as an end in itself.

No Questions Asked

The “young reformers” were in a hurry to build capitalism, and they pressed ahead in a manner that paid little attention to anything except the transformation of economic structures.

“The calculation was sober,” said Aliza Dolgova, an expert on organized crime in the office of the general prosecutor. “Create through any means a stratum in Russia that could serve as the support of reform. . . . All capital was laundered and put into circulation. No measures of any kind were enacted to prevent the legalization of criminal income. No one asked at [privatization] auctions: Where did you get the money? Enormous sums were invested in property and there was no register of owners. A policy similar to this did not exist in a single civilized country.”

Kleptocracy in the Guise of Reform

The decision to transform the economy of a huge country without the benefit of the rule of law led not to a free market democracy but to a kleptocracy with several dangerous economic and psychological features.

In the first place, the new system was characterized by bribery. All resources, at first, were in the hands of the state; businessmen thus competed to “buy” critical government officials. The winners were in a position to buy more officials, with the result that the practice of giving bribes grew up with the system.

Besides bribery, the new system was marked by institutionalized violence. Gangsters were treated like normal economic actors, which tacitly legitimized their criminal activities. At the same time, they became the partners of businessmen who used them as guards, enforcers, and debt collectors.

The new system was also characterized by pillage. Money obtained as a result of criminal activities was illegally exported to avoid the possibility of its being confiscated at some point in the future. This outflow deprived Russia of billions of dollars in resources that were needed for its development.

Perhaps more important than these economic features, however, was the new system’s social psychology, which was characterized by mass moral indifference. If under communism, universal morality was denied in favor of the supposed “interests of the working class,” under the new reform government, people lost the ability to distinguish between legal and criminal activity.

Official corruption came to be regarded as “normal,” and it was considered a sign of virtue if the official, in addition to stealing, also made an effort to fulfill his official responsibilities. Extortion also came to be regarded as normal, and vendors, through force of habit, began to regard paying protection money as part of the cost of doing business.

At the same time, officials and businessmen took no responsibility for the consequences of their actions, even if they led to hunger and death. Government officials helped organize pyramid schemes that victimized persons who were already destitute, police officials took bribes from leaders of organized crime to ignore extortion, and factory directors stole funds marked for the salaries of workers who had already gone months without pay.

Lawlessness

The young reformers were lionized in the West, but, as the years passed and the promised rebirth of Russia did not materialize, arguments broke out in Russia over whether progress was being prevented by the resistance of the Duma, inadequate assistance from the West, or the inadequacies of the Russian people themselves. These arguments, however, had a surrealistic quality because they implicitly assumed that, with the right economic combination, it was possible to build a free market democracy without the rule of law.

In fact, a market economy presupposes the rule of law because only the rule of law is able to assure the basis of a free market’s existence, which is equivalent exchange. Without law, prices are dictated not by the market but by monopolization and the use of force.

The need for a framework of law was particularly pronounced in the case of Russia because socialism for ordinary Russians, in addition to being an economic system, was also a secular religion that lent a powerful, albeit false, sense of meaning to millions of lives. When the Soviet Union fell, it was necessary to replace not only the socialist economic structures but also the “class values” that gave that system its higher sanction. This could only be done by establishing the authority of transcendent, universal values, which, as a practical matter, could only be assured by establishing the rule of law.

A Cautionary Tale

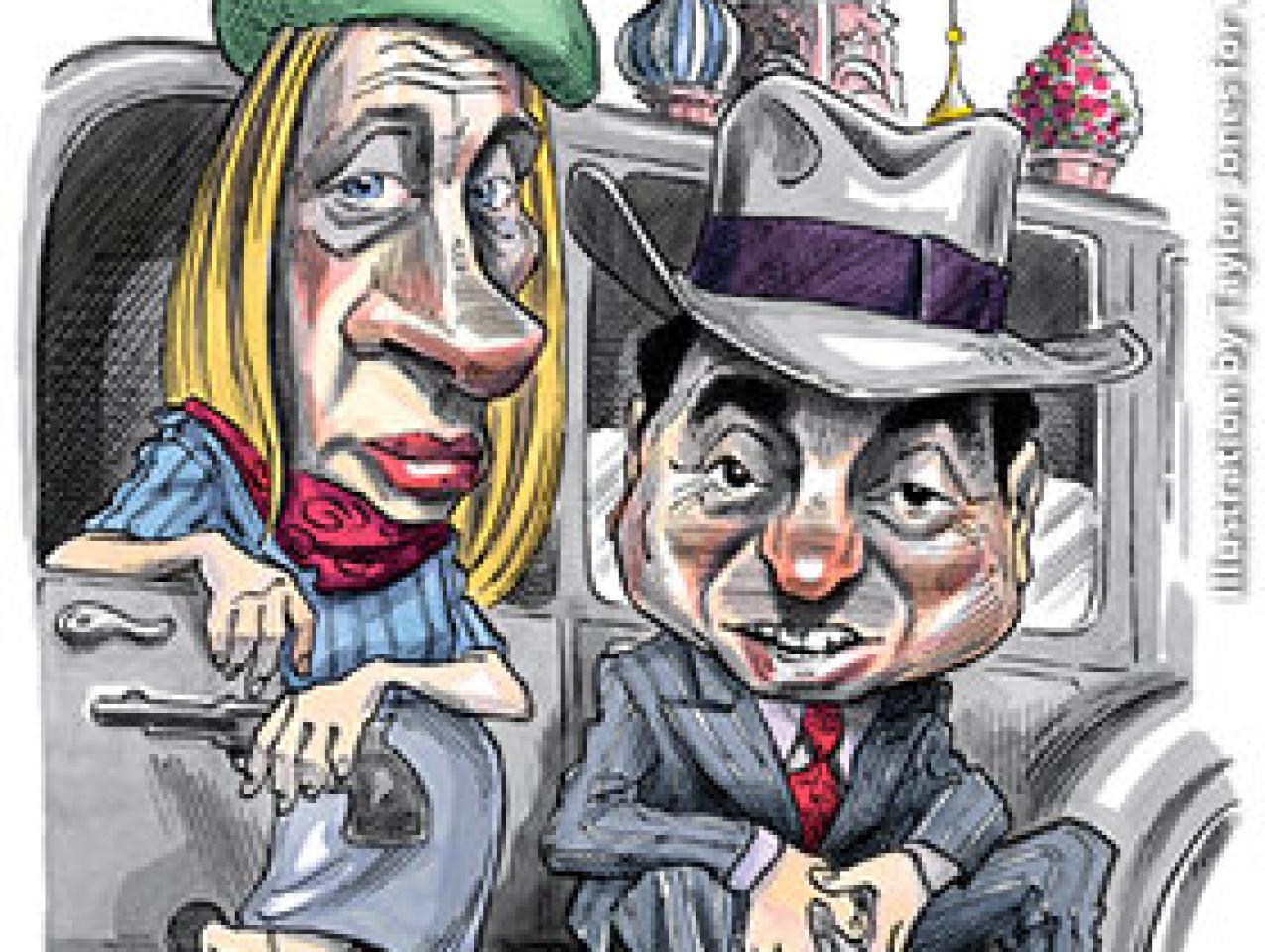

On May 10, 1997, the Greek police found in a shallow grave under an olive tree, two miles from the Athenian suburb of Saronida, the dismembered body of Svetlana Kotova, one of Russia’s top models and a former “Miss Russia.” It was learned that she had been the guest of Alexander Solonik (Sasha Makedonsky), Russia’s number one professional killer who had himself been found strangled three months earlier in the Athenian suburb of Baribobi.

Svetlana’s story evoked intense interest in Russia because of her youth and beauty and because there was something about the romance between a 21-year-old beauty queen and a professional killer that was symbolic of the condition of modern Russia.

Svetlana met Solonik in a Moscow nightclub on New Year’s night, 1997, and traveled to Greece on January 25 at his invitation. She was met at the bottom of the staircase from the airplane with armloads of flowers. Waiting for her was a Mercedes with an elegant chauffeur. The rent on the villa where she stayed was about $90,000 a year. There was a swimming pool, gym, basketball court, golf course, and gardens with sculptures. From the 26th on, she called her mother every evening and said that this was not life but a miracle.

In the villa and in Solonik’s car were a large quantity of firearms and other weapons, but it is not known whether Svetlana was aware of them. For five nights, she lived as if in a dream, but on the 30th, gangsters from the Kurgan criminal organization, a supplier of hired killers to the Russian underworld, arrived at the villa. While they were talking to Solonik, someone threw a thin cord around his neck and strangled him from behind. The visitors then came for Svetlana, who was on the second floor.

When word of Svetlana’s murder was released, the Russian newspapers were full of her pictures: Svetlana with flowing black hair in a long black gown with thin shoulder straps, Svetlana in a bathing suit looking out shyly from behind spread fingers, Svetlana with her head cupped in her hands, Svetlana in an evening dress with her hair off her forehead in a bun. From her appearance, it seemed that no one could have been less prepared for the devilish game that she had fallen into.

Yet the fate of Svetlana Kotova had something in common with the fate of her nation, which was freely delivered into the hands of criminals during the period of reform. The rewards were quick and easy. There was a willful desire not to know.

It remains to be seen whether, in the long run, Russia will share Svetlana’s fate.