- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

“When those planes flew into those buildings, the luck of America ran out,” the essayist Leon Wieseltier wrote in the aftermath of our day of grief. We hadn’t been prepared for what, and who, came our way on that day. For a good long decade, we had been mesmerized by the financial markets, by Nasdaq and the high-tech bubble. The gurus of the 1990s had announced the end of ideology, the triumph of the market, the end of history itself. Amid that triumphalism, a self-styled Saudi jihadist of Yemeni ancestry by the name of Osama bin Laden declared war against the United States, called on every Muslim “by God’s will to kill the Americans and plunder their possessions wherever he finds them and whenever he can.” On October 12, 2000, two followers of that man struck the USS Cole as it docked in Aden to refuel. Witnesses say that the assailants, who perished with seventeen of our sailors, were standing erect in their skiff at the time of the blast, as if in some kind of salute.

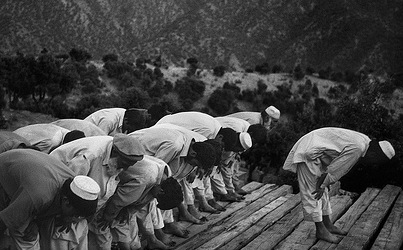

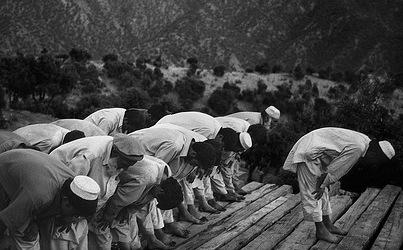

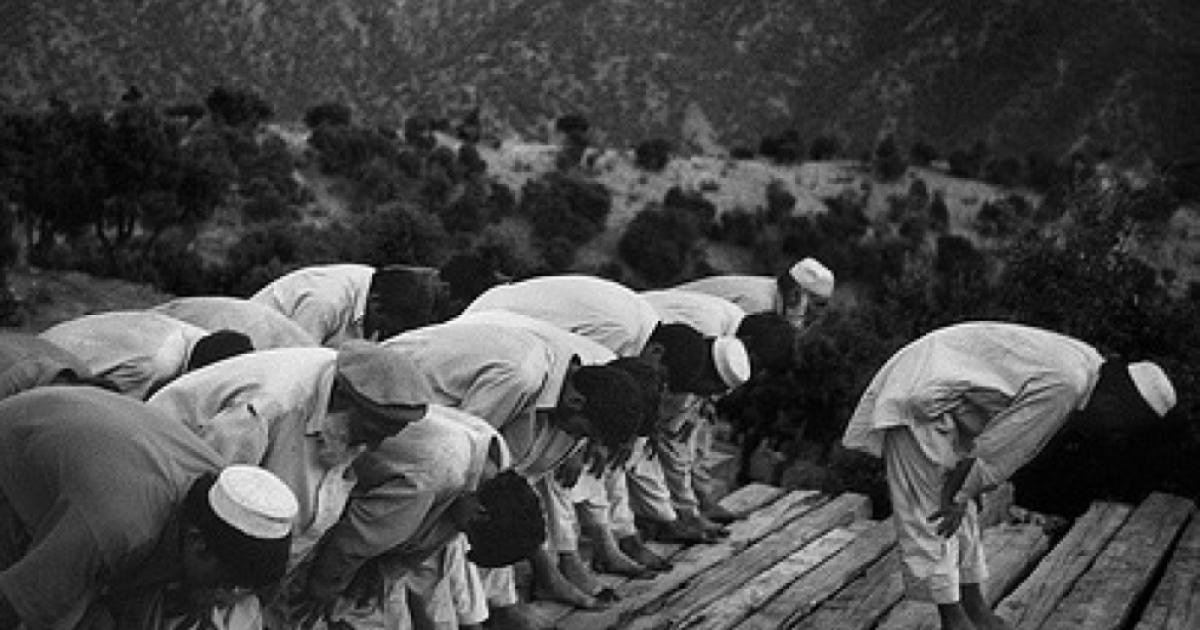

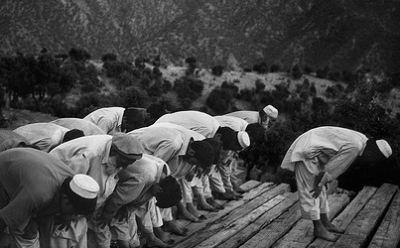

Photo credit: balazsgardi, via flickr

Now it could be said that we should have taken notice of that “declaration of war,” of the attacks on our embassies in Kenya and Tunisia in the summer of 1998, of the two men in their skiff and of a long trail of anti-American terror. But in our time of hubris, during that long bull run, we had waived it all off. Had we seen the glee ashore in Aden when that skiff had struck our mighty ship, had we been reading the tracts of a new breed of Islamist, had we half-understood the fight between the pro-American autocrats and their disaffected, militant children, we might have readied ourselves for that war. We might have refrained from downgrading our intelligence and military capabilities.

But the 1990s were the Bill Clinton era—the globalization president, he was dubbed. He had his sunny view of the world and he was convinced that wars and ideologies were a thing of the past. He was relentless in pursuit of an Israeli-Palestinian settlement, so convinced was he that the Palestine question was the source of the maladies of the region. But in that vast Islamic world, there were troubles aplenty. And there was a radicalism that paid little heed to the matter of Palestine. Islamist militants and true believers embittered in the prisons of Jordan and Egypt and Tunisia and Algeria, had prepared for a new kind of war.

In the nineties, Islamist militants were preparing for a new kind of war.

The masters of terror, the men who ran and “managed” the jihad were a resourceful lot. They sent to our shores a band of killers who knew their way around a big, modern society. We were the ultimate open society, and the plotters had no trouble making their way into our flight schools and topless nightclubs. The geography of Islam had altered over the last quarter-century. In the shaking up of continents and the great migrations, there were now mosques and religious seminaries in bilad al-kufr, the lands of unbelief. The boys of 9/11 had no trouble finding succor, and finding one another, in the storefront mosques in Hamburg and London and Jersey City. It seemed easy, and it was.

The man who headed the death pilots, Mohamed Atta, the son of a perfectly accomplished and well-off family of the Egyptian bourgeoisie, found the most tranquil of routes on his way to the North Tower. He started out in Portland, Maine, flew to Boston’s Logan Airport, and his grim deed. He and a younger Saudi sidekick rented a car from Alamo; they made a withdrawal from an ATM machine; they had their supper at Pizza Hut; they bought their box cutters from Wal-Mart, and spent the night at the Comfort Inn. Now a decade later, as I go by Maine Mall Road where Atta did all of that, thoughts of him come to me.

Born a year after the calamitous Six Day War which wrecked Egypt’s false dreams of grandeur and marked a generation, Atta had come into his own amid the debris of that defeat. He had been bullied by a cruel, disdainful father. He had made his way to Hamburg, and there found his calling, the chance to take revenge against the great, distant power that, in his view, had turned his ancient, most defined of nations, into a false “McEgypt,” dominated by hustlers and middlemen and their allies in the military. Maine must have seemed like a blur to him. Our world had shrunk, and this young man of Cairo had his homeland, and its hated Pharaoh, in mind, as he moved about the United States.

Our good and forgiving country being what it is, the gurus and fabulists of the 1990s reincarnated into interpreters of the Islamic world. The counter-jihad, as it were. The re-tooling was easy and seamless. Our country now had legions of instant Arabists and readers of Islam. It had been America’s way not to stay long in Islamic lands. We did not have the bug for these destinations, the deserts and bleak ports in that vast arc of trouble had not beguiled and hooked us in the way they had Britain in its time of primacy.

There are people beyond our shores we barely know, and we are their demons in this war.

We now had to venture into that world. We had been a fire brigade that came in when needed, but the new burdens called on us to become the cops on the beat. We didn’t know our way through the meandering alleyways of Islam’s geography, but we did the best we could. We struck at the Taliban, and they were, in the scheme of things, the easiest and most exposed of targets, the Khmer Rouge of the Greater Middle East. But those were not Afghans who had crashed the Twin Towers and hit the Pentagon. They were Arabs, and they had emerged out of the pathologies of the Arab world. They had taken their money, the prestige that came from their mastery of Arabic, the language of the Quran, their knowledge of the scripture and the theology, to South Asia.

Targeting Kabul had not sufficed, a way had to be found into the Arab world itself, a proper “return address” for the terror that had struck us. This was a frustrating, impenetrable culture. There were regimes now asking for indulgence for their own terrible wars against Islamist enemies at home. There were chameleons good at posing as America’s friends but never turning up when needed. There was glee that America had gotten its comeuppance; in east Jerusalem, sweets were handed out to passersby in celebration of America’s grief. Before long, America would be at war, in Baghdad. An Arab target had been chosen. And for a fleeting moment, there was unity in America. But it would be torn asunder, we would have a schism over the wisdom and the means of that war.

A decade later, it is hard to be certain as to what remains of the burdens thrust upon our country by 9/11. America is a blissfully forgetful country. In this land of great changes, a decade is eternity itself. We don’t nurse feuds here in the manner of old societies. We have hunted down Osama bin Laden, and our officials tell us that Al Qaeda is on the run, that it is without money or new recruits, that its leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, lacks the charisma of his predecessor. And that the Arab Spring has given hope that the lure of the anti-American jihad has died among the Arabs themselves. We want to give credence to all that, and yet, still, we worry and wonder. After all, it had been at a time of our certainty and repose that the conspirators were at work, divining the ways they could bring us down to earth. There are people beyond our shores we barely know, and we are their demons in a drawn-out, twilight war.