- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- US Labor Market

- Education

- US

- World

- Economic

- Contemporary

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

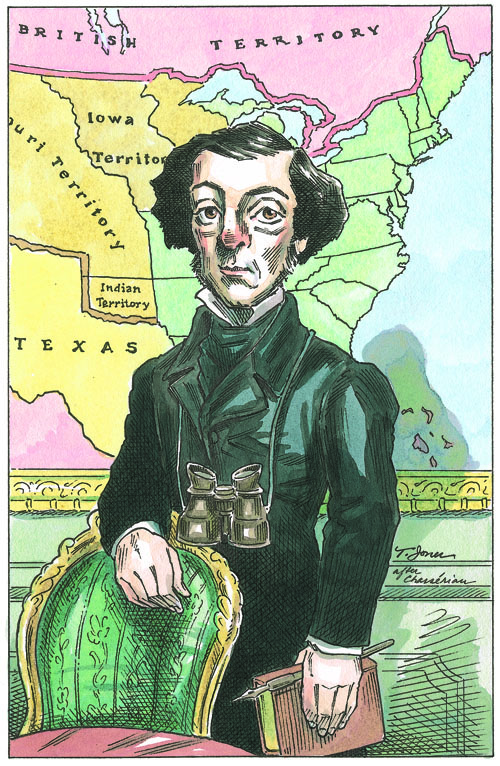

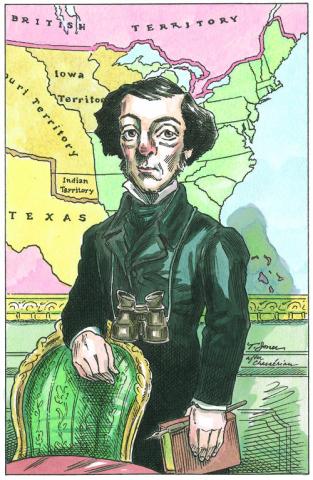

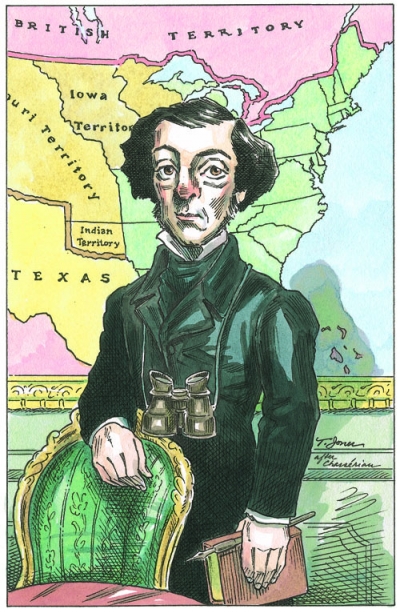

Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America is a book that every American who reads should read. There’s no better book on democracy and none better on America, first home of modern democracy.

Among a wave of new translations and analyses in recent years, two books provide elegant decoration for Tocqueville’s masterpiece.

In Letters from America (Yale University Press, 2010), Frederick Brown has edited and translated a handy collection of the letters Tocqueville wrote while traveling through America in 1831–32, speaking with Americans and gathering documents in preparation for his book. Olivier Zunz and Arthur Goldhammer have produced a tome fit for a generous gift, containing the same letters as in Brown’s collection plus Tocqueville’s travel notebooks, narrations of his side trip to the frontier, later letters, other writings on America, and ample selections of writings from Tocqueville’s friend and companion on the trip, Gustave de Beaumont. This book, Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont in America: Their Friendship and Their Travels (University of Virginia Press, 2010), even includes pictures of American birds that Tocqueville and Beaumont shot so that Beaumont could paint them—thus illustrating Tocqueville’s uncanny appeal to both the left (lovers of nature) and the right (lovers of hunting).

Two questions arise from the materials of Tocqueville’s trip and his preparations for his book, whose first volume appeared in 1835. First, what did he learn by coming to America instead of examining it from afar? Second, how—by what method—did he learn what he wrote so convincingly and profoundly? These questions engage the assertion known today as American exceptionalism, a recent issue between Republicans, who trumpet it as the justification for American patriotism, and Democrats, who deprecate it and imply that America is nothing special, unless it is special to be the leader of all other unexceptional countries.

Tocqueville thought America to be singular quite apart from the favorable circumstances permitting it to grow and flourish on its own without much interference from Europe. In the introduction to his book, he said he saw in America “more than America . . . an image of democracy itself.” Special to America was not only that it believed in democracy and practiced it as best it could, as if straining to fulfill the demands of a theory of democracy. Rather, the theory or the “image” was shown in the practice of democracy, because America was democracy complete and as a whole, the material and source of its image.

In speaking of democracy in America—the title of his book—Tocqueville confirmed and went beyond what Alexander Hamilton said on the first page of The Federalist by way of explaining American exceptionalism. Hamilton wrote that America was deciding by its conduct and example the question of whether good government could be thoughtfully chosen or was just a matter of chance. America was special because it would answer a theoretical question never before answered, not by thinking up a new theory but by means of its own practice. Tocqueville agreed and then actually found the new theory in its practice. His book on America told the rest of the civilized world what to expect in its future, as America was unique in displaying a complete democracy. It was not unique in being superior to all other peoples for all time, as implied in the boastful, irritable American patriotism Tocqueville found so objectionable.

Tocqueville was not friendly to philosophers or “theoreticians,” as several letters confirm. In Democracy in America, he ignored the political philosophy in the principles of America’s founding, calling the Puritans and not, say, John Locke, America’s “point of departure.” He emphasized the practical work of the Constitution (based on theories, to be sure) and never even mentioned Jefferson’s more theoretical and Lockean Declaration of Independence. Yet Tocqueville was interested in “theoretical consequences.” In a letter to a cousin written in 1834 (published only in the Zunz volume) he noted that it is “ten years since I conceived most of the ideas” of his book. “I went to America only to remove my remaining doubts.” Ten years before, Tocqueville was nineteen years old! He did not get his ideas from his trip to America but thought them up years before. He came to America to see “what a great republic is,” knowing what it is in advance. In Democracy in America, he noted it was only of the variety of associational activity there that he “had no idea” before he came.

To this definition and endorsement of American exceptionalism one might object, and doubters of that idea today do object, that a country maintaining slavery could not congratulate itself for being an example, let alone the exemplar, of political freedom or thoughtful choice to the rest of mankind. Tocqueville agreed, and in his letters on America after his visit he inveighed against the taint put by slavery on America’s reputation around the world, particularly since other countries had already abolished it. After the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 he grew increasingly concerned; it was one thing not to abolish slavery where it was long established, quite another to extend it to new territories. This was a point made by Lincoln, but Tocqueville died in 1859 without learning of the man who would have shown him the greatness he most praised: great thought from the doer of great deeds.

In Democracy in America, Tocqueville treated slavery as an instance of majority tyranny. As such it belongs to democracy; it is the characteristic vice, the continual threat in democracy. That is why he could say that America revealed what a complete democracy is. Democratic justice is always accompanied by democratic injustice. The reason why slavery continued for so long in America is that the majority was behind it, and when the crisis came—shortly after Tocqueville’s death—Lincoln saw that although there was a majority in the country against slavery, there was not a majority for war to abolish it. After the election of 1860, he was able to rally a majority for a war to save the Union in the course of which, with much bloodshed, slavery was abolished. As Tocqueville foresaw, it was because of democracy that democracy had such trouble cleansing itself.

In his book, Tocqueville contrasted the fates in America of blacks and Indians, the former enslaved by democratic prejudice and the latter cheated in unfair treaties by democratic hypocrisy. On his trip, too, he had shown equal interest in the two sets of victims, and the Zunz volume contains Goldhammer’s fine new translation of “Two Weeks in the Wilderness” (until now usually known as “Fortnight”). This work of forty pages, composed on a steamboat on Lake Huron, is a demonstration of the prodigious energy Tocqueville commanded on his trip. It is a reflection on man and nature so beautifully done that it can be thought romantic, but it is not so hostile to civilization as is romanticism. Indians in his view are free and noble in their extreme way, but they remain savages unable to accept the benefits of reason and civilization that would moderate and improve their intractable souls.

And the question of Tocqueville’s method? One must first confront the uncomfortable truth that his genius was indispensable. To see the difference between a genius and a non-genius one could begin with the difference between Tocqueville, who wrote a great book, and his friend Beaumont, who wrote a mediocre one. The two shared the investigation into American penitentiaries that was the “pretext” (Tocqueville’s word) for their trip, and Beaumont spoke proudly in July 1831 of “our great work” on America, the real object of their voyage, that was to come. But by November, he understood that Tocqueville was writing that book on his own and that he was to write a fictional treatment of slavery—“the great work that is to immortalize me,” he noted wryly. After Tocqueville’s death, Beaumont edited his works, and one could say of him that he was as true a friend as he knew how.

Tocqueville made “travel notebooks” that are translated in the Zunz collection. These are transcripts of his questioning of his sources appearing as dialogues between “Q” and “A” and contrasting nicely with modern survey research techniques. Tocqueville asks intelligent questions of intelligent people and presses them to face their contradictions and explain themselves; he thinks and learns as he surveys. Today’s survey researcher asks bland questions of average respondents, has an assistant code the responses, restates and manipulates them mathematically, and then interprets them according to a model that he can persuade his professional colleagues to accept.

Which method produces the better result? To answer the question, consider that Tocqueville addresses the question of American exceptionalism, the question of what America is all about, while social science assumes it is meaningless or unanswerable and evades it. In our time we can hardly read too much Tocqueville.