A Laborite Israeli political scientist, Asher Susser, first presented me with the arguments for a withdrawal from the West Bank and Gaza Strip coupled with the erection of a security fence to keep Palestinian terrorists out. That was in the spring of 2002. More than 500 Israeli lives had already been lost to the wave of Palestinian suicide bombers who had become the signature of Intifada II (which began in September 2000), just as the rock-throwing teenager had been the signature of Intifada I in the late 1980s. The government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon had responded with pulverizing attacks against terrorists and those who sheltered them and had established a system of checkpoints and roadblocks throughout the occupied territories that made ordinary commerce impossible for Palestinian residents, costing many their livelihoods and making life’s simplest transactions a daily ordeal. Now and then the Israelis would aim bombs or rockets at one senior terrorist leader or another. Although more discriminating than the Palestinian suicide bombings, the Israeli attacks often struck the heart of towns or villages, killing innocent civilians along with their intended targets.

Reflecting on these events in his spartan office at Tel Aviv University, Professor Susser extended no sympathy to Palestinian subjects of Israeli retaliation. Like most of his liberal colleagues, he had been appalled at Yasser Arafat’s rejection of former prime minister Ehud Barak’s Camp David peace offer and his obvious subsequent support for those conducting murderous attacks against Israeli civilians. Susser had put his faith in the 1993 Oslo Accord, which had postponed the difficult “final-status issues”—borders, Jerusalem, settlements, and refugees—in the hope that the parties would, through staged implementation of other (less contentious) provisions, develop the body of trust needed to achieve a final deal.

Now, despite his disillusionment, Susser did not think Israelis should be maintaining or even expanding settlements on Palestinian land. Nor did he think Israel would ever be able to move beyond its heavy-handed counterterrorism techniques as long as it occupied Palestinian territory. “The Palestinians’ greatest victory is what we have become in the process of fighting them. We cannot continue to let them define our conduct, our values, our qualities as a society,” he said. “Once we are again living within our rightful borders we will be able to defend our state. We always have. There is no need to occupy their land.” Many of Susser’s fellow liberals also embraced a policy of “separation” of the two peoples, including construction of the wall between Israeli and Palestinian lands.

Much of the Israeli military and nearly the entire political right, including Prime Minister Sharon, had grave reservations about what might be called the “withdrawal to a wall” strategy. One senior military commander with whom I spoke bitterly recalled internal debates before the pullout from Lebanon in 2002. Despite the cost and occasional loss of life involved in maintaining the narrow “security zone” in southern Lebanon, military leaders had argued that their Shiite foes would celebrate a unilateral withdrawal as a substantial victory, a sign that Israel was unwilling to sustain the price of conquest, a notion that would not be lost on Arafat and his compatriots. The Palestinians would reoccupy any land from which the Israelis withdrew and continue their jihad against the Jewish state. And unlike Lebanon—which involved a withdrawal to internationally recognized borders, together with U.N. certification that Israel was in compliance with applicable resolutions—a unilateral Israeli withdrawal, even from most of Gaza and the West Bank, would still leave all final-status issues, including borders, unresolved.

Moreover, knowing that at least half the suicide bombers who had struck inside Israel had used disguises and false documentation to elude checkpoint guards, a consensus of military leaders felt the security benefits of a wall would be marginal. Sharon and many of his Likud allies also feared the wall would become a de facto boundary for the state of Israel, excluding settlements and territory they wanted to retain. But with his Laborite coalition partners committed to the wall and the Intifada at its most virulent stage, Sharon relented and ordered construction to begin.

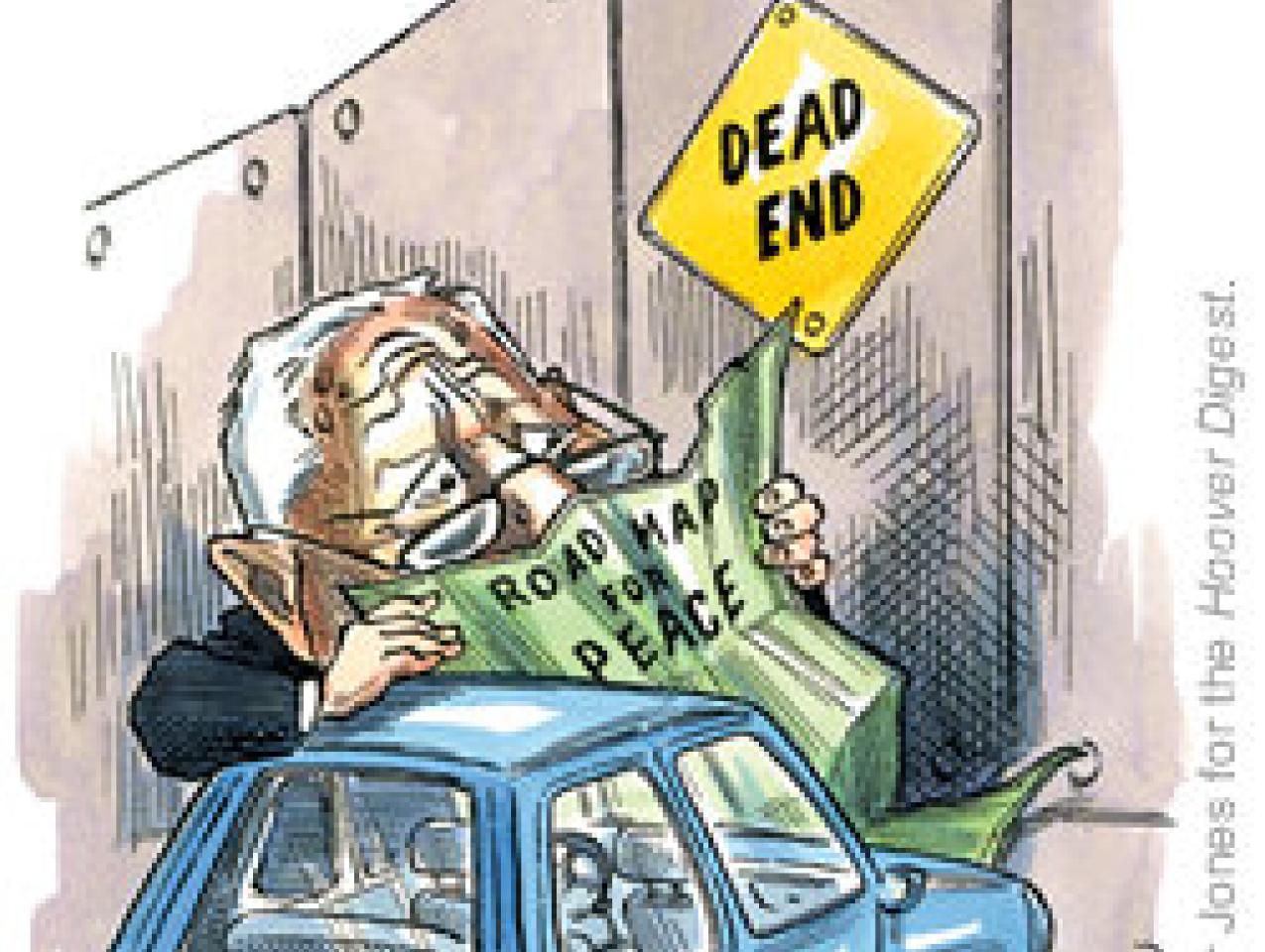

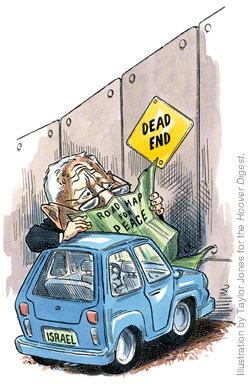

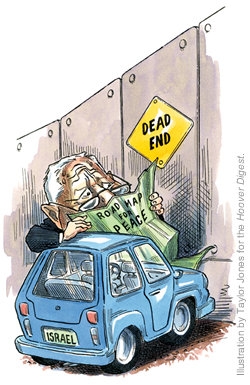

In the United States, the Bush administration appeared to pay only perfunctory attention to Israel’s decision to construct a wall. Its immediate priority was building a coalition of nations willing to support the invasion of Iraq. Toward that end, President Bush accepted the request of British prime minister Tony Blair, who was providing unwavering support on Iraq, that Washington endorse a European-conceived “road map” for peace between Israel and the Palestinians.

Road map to Where?

In its first phase, the road map called for Israel and the Palestinians to declare an immediate cease-fire, to again endorse a two-state solution to their dispute, and to begin immediate security cooperation. Meanwhile, the Palestinians would commence building political institutions that reflected democratic values, and the Israelis would disband all settlements constructed since the start of the Intifada. During the second phase, the Palestinians would enjoy an independent state with provisional borders, the two sides would broaden their economic, security, and negotiating contacts, and neighboring Arab states such as Jordan and Egypt would be encouraged to resume their pre-Intifada relations with Israel. In phase three, to be achieved in 2005, the parties would reach accord on “permanent-status” arrangements. Throughout the three-year process, Israel and the Palestinians would be aided by a “quartet” of international parties committed to the peace effort: the United States, the European Union, the United Nations, and Russia.

One central problem with the road-map approach was that it was put forward with a dizzying lack of appreciation of conditions on the ground. Because many of Arafat’s security personnel had participated directly in the armed Intifada, Israel had systematically destroyed police stations, militia facilities, and all kinds of military hardware and software, undermining the ability of Arafat to control the activities of extremists, even had he desired to. Moreover, the Palestinian Authority (PA) leader was himself cooped up at his bunker headquarters in Ramallah, the Israelis believing, with considerable justification, that although the violence may have commenced without his personal involvement, he had soon adopted Intifada II as his own, financing and helping to direct violence against Israel, in part because it was the only way for him to maintain the support of angry constituents, and in part because in his heart he could never accept a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. Further, during the nearly two years of turmoil, such extremist movements as Hamas and Islamic Jihad had enjoyed a surge in support among the Palestinian population and now claimed the allegiance of perhaps 35 percent of that population, compared to about 15 percent before the fighting had begun.

Assassinating Palestinian leaders complicit in the terrorism—an Israeli tactic that goes back to retaliation for the slaughter of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics—while hard to fault in moral terms, changes little on the ground. For every Sheik Ahmed Yassin, the Hamas leader killed by the Israelis in March, a no less militant replacement, such as Dr. Abdel Aziz Rantisi, stands ready to begin his own journey to martyrdom.

The road-map approach also ignored the structural change in the Israeli political community. Oslo, with its confidence-building, incremental approach, was now a bad memory.

Drawn-out procedures only provided opportunities for the virus of terror to spread more completely. Extremism also spawned expansive goals on the West Bank and Gaza regarding what the fight was all about. For example, as early as the spring of 2002, Palestinian polls indicated that a majority of Palestinians saw the stakes of the Intifada as the elimination of Israel itself, not merely an end to the occupation. For all this, most Israelis blamed Oslo. And now the quartet was peddling “Oslo Lite,” the road map, which Prime Minister Sharon endorsed only to remain in favor with the Bush administration. In terms of significant progress, there was none.

The most glaring weakness in the road-map approach was its failure to articulate what the parties could expect at the end of the process. A Palestinian state was simply too amorphous. Given the specificity negotiators had achieved at Camp David and at the last-ditch Taba talks that concluded in January 2001, the road map was like stepping back to the outset of the Oslo process, with a somewhat more ambitious timetable but, like Oslo, a timetable wholly dependent on the ability of negotiators to crack the tough issues. Meanwhile events created their own momentum. After several suicide bombings in the spring of 2002, the Sharon government, with the support of the Bush administration, reoccupied the entire West Bank. In June President Bush demanded political reform of the Palestinian Authority as a precondition to negotiations and said that Israel would not be expected to negotiate with any individual compromised by involvement with terror, a clear reference to Arafat. Goaded by Washington and, to some extent, by their own intelligentsia, Palestinians did begin a desultory process of political reform. But two years and two prime ministers later, Arafat still appeared to exercise decisive political control.

Alternative Approaches

Frustration with the lack of progress has produced two significant initiatives by “private” Israeli and Palestinian citizens hoping to engineer a breakthrough. In July 2003, Ami Ayalon (the former director of Israel’s Shin Bet security agency) and Sari Nusseibeh (president of Al Quds University and formerly a PA official) concurred on a Statement of Principles, which they then circulated within both communities and which has received tens of thousands of signed endorsements in each.

A second, far more ambitious undertaking came to fruition in October 2003, when teams of unofficial Israeli and Palestinian delegates successfully concluded months of negotiations in Geneva on a purportedly comprehensive agreement (“Virtual Geneva”).

The two deals were similar in that they each provided for a demilitarized Palestinian state embracing a connected Gaza Strip and West Bank with an East Jerusalem capital. Both permitted Israel to annex heavily populated settlements on the outskirts of Jerusalem in return for the Palestinian right to annex small areas of pre-1967 Israel. The two accords would have resulted in closure of all Gaza settlements and more than 75 percent of the post-1967 settlements established on the West Bank, the latter acceptable to most Labor Party members and other leftist parties but anathema to most of the Likud Party and its right-wing allies who either see “Judea” and “Sammaria” as essential parts of the “Land of Israel” or who argue that security demands more-extensive Israeli landholdings.

The two deals diverged slightly on the so-called “right of return,” the ability of refugees and the descendants of refugees who left or were driven from Israel during the 1948 war securing Israel’s survival as a state. Most Israelis, whatever their politics, believe that the return of large numbers of Palestinians to areas inside the state of Israel—as opposed to areas inside the new Palestinian state—is a formula for demographic suicide that could, within a few decades, lead to the eradication of the Jewish state. Palestinian negotiators have in the past expressed a willingness to compromise on the modalities of return but not on the basic right. The Nusseibeh-Ayalon principles would extinguish the right; Virtual Geneva is somewhat more ambiguous on the subject.

There was some enthusiasm for Virtual Geneva, particularly at the State Department, where many would welcome more active U.S. involvement in the search for peace. Secretary of State Colin Powell met with and congratulated the chief negotiators, but he noted that the United States remains committed to the road map. In Jerusalem, the Sharon government disowned Virtual Geneva as a near-treasonous act by its Israeli participants. Quite apart from its waffling on the right of return, Sharon and his colleagues—like most of the planet’s governments—have little taste for private diplomacy conducted by the “outs.”

But even among members of the Likud there was growing recognition that the status quo is unacceptable. One reason is the cost of the flickering but still troublesome Intifada, particularly on the country’s tourism-dependent economy. Another is the growing demographic threat to Israel posed not by allowing Palestinian refugees to return to the Israel of 1948 but by stretching Israel’s borders to embrace a large and expanding Palestinian population. Within a few years Muslims will outnumber Jews in the areas embraced by Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. When that happens, the Palestinian political agenda may switch from a two-state solution to the demand for majority rule in a single country, forcing Israel to choose between its religious and democratic political heritages. A third reason is distrust of Arafat and the Palestinians. With or without Arafat, the Likud—like the population generally—wants no Oslo redux. Defensible borders, they say, are more important than negotiated borders, and particularly with the erasure of the Iraqi threat from the east, Israel’s borders have never been more defensible.

Thus, along with Asher Susser and those liberals who think like him, many in the Likud are starting to talk about unilateral withdrawal. But, unlike the liberals, the Likud officials speak of something far more modest than a pullback to the 1967 borders. Yuval Steinitz, for example, chairman of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, has called for an Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, leaving Palestinians to form their state there. Ehud Olmert, mayor of Jerusalem and a deputy prime minister, wants to abandon both the Gaza Strip and many of the more remote West Bank settlements. Others condition a partial Israeli withdrawal on the assertion of sovereignty over the remaining land, a formula that reportedly piqued the interest of Prime Minster Sharon but one he now has disowned.

The Likud versions have in common the notion of partial unilateral withdrawal, an approach that suffers from all of the drawbacks of the more

complete liberal pullback and adds a few of its own. The action could be interpreted by Palestinian extremists as a retreat, enhancing the stature, the political power, and quite likely the terrorist agenda of groups like Hamas. And to the extent that the Israeli action was interpreted as an appropriation of Palestinian land, the Palestinian position would find reinforcement in the international arena because no one, not even the United States, would recognize new, unilaterally established Israeli borders. Should Israel unilaterally assert soverignty over additional portions of the West Bank, world opinion would hold the action illegal and provocative. And this time world opinion would be right.

Moreover, the benefits Israel could achieve at appropriately structured negotiations cannot be dismissed lightly. For example, Virtual Geneva provides for a multinational force to supervise the accords as well as a handsome package of security-related benefits impossible to achieve through unilateral action.

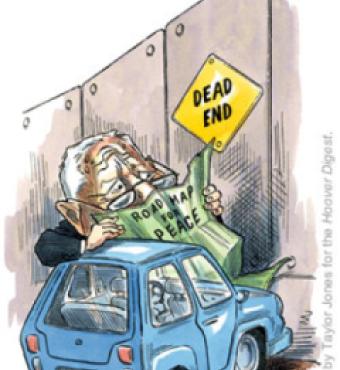

But as long as the United States remains committed to a road map that points directly to a dead-end street, there will be no progress toward peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, only continued strife, death, and human tragedy. Dwelling on process is not the way to achieve a breakthrough. Rather, the Bush administration should boldly share with the parties and other key regional and international players a very specific vision of what peace can bring, beyond the simplistic homily of a Palestinian state. The administration should then press key Arab states, our European friends, and other relevant parties to endorse its plan and to use their weight to make it work. The right kind of agreement—say Virtual Geneva with clearer restrictions on the right of return—could even lead extremist groups such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad to moderate their behavior, as both have shown a past reluctance to defy public opinion in the Palestinian community.

In diplomacy, as in war, timing is everything. The moment is approaching when negotiations with the Palestinians will be less a reward for terror than a way for both sides to consolidate political gains derived from their mutual recognition and willingness to make peace on the basis of principles set forth in advance with precision and particularity. The great Palestinian concession must involve yielding the right of return, and the great Israeli concession must involve closing settlements. Aside from the Jerusalem suburbs, which Israel would annex, the settlements on the West Bank and Gaza Strip are monuments to the fanaticism of the few compounded by the political cowardice of the many. They should revert to the Palestinians as part of a negotiated peace. Withdrawing from selected settlements unilaterally makes no more sense than building them in the first place. To the contrary, it is only a formula for prolonging the conflict.