- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- US

- Contemporary

- Military

- World

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- History

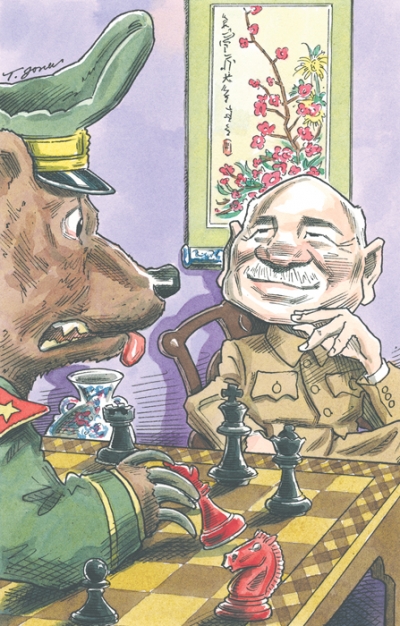

Nearly a decade after the Sino-Soviet split, Victor Louis, a Russian correspondent for the London Evening News who reputedly had KGB connections, visited Taiwan for ten days. In meetings with Nationalist officials, principally Defense Minister Chiang Ching-kuo, he proffered Soviet cooperation for a joint attack on mainland China. Louis’s visit in October 1968 and his subsequent contacts with Taiwan have been widely reported upon and analyzed by scholars, but until very recently certain key details had never been revealed.

What were the terms of cooperation under consideration by Russia and Taiwan? To what extent was Chiang Kai-shek, president of the Republic of China on Taiwan, personally involved in this episode? And perhaps most important, why did Chiang ultimately decline to exercise the Russia option in his long struggle with the Chinese Communists?

Many of the answers lie in portions of Chiang Kai-shek’s diaries, housed at the Hoover Institution, that were released in July 2009. These volumes, which cover Chiang’s final collection of entries (1956–72), provide for the first time detailed information on this highly intriguing Cold War engagement.

POINT AND COUNTERPOINT

After receiving Chiang Ching-kuo’s report on his meetings with Louis, Chiang Kai-shek took immediate charge of the negotiations and recorded them in his diaries. Numerous entries in 1969 and, with less frequency, in 1970–72 reveal how Chiang pondered the Russian offers and framed Taiwan’s response. The central figures in the negotiations were Louis and, representing Chiang Kai-shek, Wei Jingmeng, a confidant of Chiang Ching-kuo and former director of the Republic of China’s information office. The Louis-Wei rendezvous took place in Taipei, Vienna, and other places not identified.

The Russia-Taiwan contacts, however, were not limited to the meetings between Louis and Wei. Indeed, they spanned several continents, involving many diplomats and journalists. Among them were meetings between Wang Shuming (head of Taiwan’s military mission to the United Nations and a onetime chief of staff of the Nationalist army) and Russians in New York; a reporter from Taiwan and a Russian reporter in Tokyo; Taiwan’s ambassador to Mexico, Chen Zhiping, and his Soviet counterpart in Mexico; Taiwan’s ambassador to Japan, Peng Mengji, and his Soviet counterpart in Japan; Song Fengsi, a reporter from Taiwan, and a Soviet officer in West Berlin; and Taiwan’s and Russia’s ambassadors to Brazil. Some of these contacts continued well into 1972, while others appear to be one-time liaisons.

Chiang apparently channeled the information he gathered from these contacts to Wei and instructed him to exchange concrete proposals with Louis. After the first round of talks, Wei in April 1969 relayed Louis’s first set of terms to Chiang. As paraphrased from Chiang’s diary entries, they were:

- The two sides would conduct negotiations for purposes of mutual understanding and mutual benefit, without preconditions.

- One side would not interfere with the internal politics of the other side.

- All political parties in Taiwan would be under the direction of the Nationalist government.

- The Taiwanese side should not conduct any propaganda campaign on this matter.

- The Taiwanese side should not receive assistance from any other foreign country.

- The Russian side would not create any governmental organization or military force in China.

- The Russian side would provide assistance only to the Nationalist government, not to any political party or faction in Taiwan.

Chiang paid close attention to the stipulation that the Taiwanese side should not receive assistance from any other foreign country, considering it a Russian ploy to drive a wedge into his relations with the United States. Chiang’s government apparently had informed the United States of the ongoing negotiations, and Chiang had learned that the American ambassador to Taiwan had expressed “neither opposition to nor endorsement of” the negotiations. Yet the issue of relations with the United States would be important later.

In the spring of 1969, a sharp deterioration in Soviet relations with Communist China resulted in military clashes on Zhenbao Island (Damansky) on the Chinese-Russian border river, the Ussuri. Talks of a Soviet pre-emptive strike on the Chinese nuclear facilities were afoot as hundreds of thousands of Russian troops were deployed along the long Chinese-Russian frontier. Louis kept in constant touch with Wei during April and May, vigorously pushing for military cooperation between the forces of the Soviet Union and Taiwan.

Chiang, however, remained cautious. Relying on Wei’s briefings, he assessed the Soviet position as follows:

- 1. Russia is so eager in seeking our government’s [cooperation] that it is willing to lend its military bases to us, and it intends to invade Xin-jiang, thereby solving its problem [with the Chinese Communists].

2. It does not emphasize a policy of cooperative coexistence of our two nations. . . .

3. Its ultimate objective is to create a new Chinese Communist regime to rule China.

4. It will use its weapon [offer] as the only means to lure us [into cooperation with it]. It does not have a sincere desire for rendering [meaningful] assistance to us.

Two days later, Chiang commented further on the Louis-Wei exchange:

- 1. Louis has again urgently asked us to forward to him a list of weapons we need [from Russia]. He is attempting to use the list as a bargaining chip in a deal with us. For that reason, we should not provide him with the list so that he could not exert pressure on us.

2. As for dispatching a formal representative [from Russia to Taiwan], he did not reject the idea, only saying that finding [a proper] means of transportation is difficult and that a high-ranking [Russian] officer could not come [to Taiwan] under disguise.

3. He is not emphasizing negotiation on political matters, only saying that anything could be discussed once the Mao regime is toppled. From this I can see that in its policy toward China, Russia is not taking us seriously as its primary partner.

Chiang soon came to the conclusion that the Russians were interested only in making use of the Chinese Nationalist forces for a yet-unspecified objective, without any intention of engaging in a broad political collaboration. Not surprised by the Russian position, Chiang considered it only natural that the two sides would make use of each other for their own purposes. He reminded himself to deliberate carefully on the matters to be negotiated so that he would be sure to benefit from them.

RUMBLINGS OF A NUCLEAR DANGER

In June, Chiang recorded Louis’s talks with Wei on military collaboration:

- Louis is urgently asking us to designate personnel in Europe as liaisons [with Russia]; he said it would be difficult to talk on this matter once war starts. He hoped we would present at the next meeting a list of military items [we need from Russia].

I believe we should pay special attention to the following:

1. Louis made the point that [Russian] weapons do not have to be shipped in total to Taiwan . . . but [some of them] could be delivered directly to the vicinity of our landing sites [when we launch our attack on the mainland].

2. He said we must work out detailed plans with Russia on the country’s support of our attack on the mainland.

3. [These plans] would concern, for instance, how to make use of Russian military bases and what types and quantity of weapons are needed in what battle areas.

4. The Russians could create border disputes [with Communist China] during our landing operations.

5. Because the prevailing tense international situation is unpredictable and rapidly changeable, the Russians may find it necessary to come to Taiwan [for consultation]; hence Taiwan should alert its embassies abroad to be ready to provide them with visas.

Still wary of Louis, Chiang refused to authorize discussion with him on the specifics of weapon assistance. In August, Chiang learned of a new border clash between the Russian and the Chinese forces not in Manchuria, as before, but in Xinjiang, northwestern China. He now believed that the tension between the Russian and Chinese Communists was centered more in Xinjiang than Manchuria.

By early September, when rumors about a possible Russian pre-emptive strike on Chinese nuclear facilities had again appeared in the news, Chiang commented, “In seeking our cooperation, Russia is now setting the destruction of Chinese Communists’ nuclear facilities as its top priority. To overthrow the Mao regime becomes its secondary objective. And the idea of creating a Nationalist-Communist government is also under consideration.”

Chiang considered his exchanges with the Russians, though intensive, to be still exploratory. Yet he felt that he now needed to make a comprehensive response, prompted in no small measure by the issue of nuclear weapons. He was concerned that his contacts with the Russians might “prompt the Chinese Communists to use their short-range or intermediate-range atomic weapons to strike us.” On the other hand, he pondered whether such a strike might give the Russians an excuse to attack China, thus deterring the Communists. He noted with increasing concern that the Chinese Communists had conducted an underground nuclear test in Xinjiang on September 22 and an air-drop nuclear test—their ninth—on September 29.

On October 1, he set forth his terms of cooperation with the Russians:

- Chiang would maintain complete independence in Chinese foreign policy, not subject to any restriction.

- He would maintain Chinese territorial integrity and administrative independence without allowing foreign interference.

- He would guarantee these three points through an oral statement:

- 1. After recovery of the Chinese mainland, he would not permit any foreign power to create anti-Russian bases on Chinese soil.

- 2. He would not conclude an anti-Russian alliance with any foreign power.

- 3. He would permit Chinese-Russian joint economic development of Chinese areas bordering Russia on a mutual assistance and equitable basis.

Chiang also contemplated at this time how to cooperate with the Russians to destroy the Chinese Communist nuclear weapons in localities most threatening to Taiwan—south of the Yangzi River—and then those in northern China.

THE DENOUEMENT

Suddenly, just as Chiang turned serious in his negotiations, Russia lost interest. Louis failed to show up for a scheduled meeting with Wei in Italy in October; Chiang suspected that his absence was deliberate. During the rest of 1969, Chiang’s diary made no further reference to Taiwan’s contact with the Russians. Not until the next April did he return to the subject, pointing out then that the Russian attitude had been changeable and unpredictable. For the next two years, until April 21, 1972, Chiang’s diaries showed that Taiwan remained in contact with the Russians, but the liaison became increasingly sporadic, and nothing of substance came out of it.

Looking at all of Chiang’s diary entries relevant to the Louis episode, one may identify two reasons why the Russia option never came to pass. The first is that the Soviets—after a meeting between Premiers Aleksei Kosygin and Zhou Enlai in Beijing in September 1969—began that fall to ease tensions with the Chinese Communists. Chiang thought this was part of the reason Louis failed to show up to meet with Wei. He observed that Russia and Communist China had started negotiations in Beijing on October 20 to settle the Manchurian border dispute; those talks went on intermittently until December 18, 1970, and resulted in a treaty. That treaty apparently lessened the prospect of war between the Soviet Union and China, thus making Russia’s approach to Taiwan for military cooperation less urgent. (The border settlement, however, did not fundamentally alter the hostile relations of the two Communist nations. Thus, the Russians continued to engage in talks with Taiwan, through Louis and Wei—who had resumed contact—as well as ambassadors [1970–72] in Mexico City and Tokyo.)

The second reason these lingering contacts resulted in no cooperative arrangement—military or otherwise—was Chiang’s resistant frame of mind. From the beginning of Louis’s contact with Wei, Chiang had shown a strong distrust of the Russians. He characterized them as “cunning” and reminded himself to guard carefully against their “fraudulent” activities. No doubt he had in mind that Russia had acquired through chicanery and outright aggression many pieces of Chinese land since mid-Qing times. And he often lamented that Russia had gained unjustified advantages over China through the Yalta Agreement of 1945.

That is why he warned Wei to be vigilant when dealing with Louis and why he repeatedly refused to supply the Russians a list of weapons he might need. And he was especially conscious of the danger of a joint military adventure with the Russians. He cited a well-known Chinese historical episode as a warning to himself. In that episode, General Wu Sangui of the Ming Dynasty appealed to the Manchu army for help as a rebellion threatened the dynasty’s existence. The invited Manchu army did suppress the rebels, but went on to topple the Ming as well.

With the danger in mind, Chiang nevertheless engaged in talks with the Russians because he would explore any possibility that might help him realize a goal he considered as important as his own life: recovery of the lost Chinese mainland. “Anyone helping me recover the mainland is my friend,” he once wrote as he weighed the Russia option. “Otherwise, he is my enemy.”

But late into negotiations, he met a Russian condition he could not accept. “The Russians have taken the United States as an enemy, not a friend,” he wrote in June 1970. “And they have told us that the only condition for their cooperation is that we must act against the United States.” He branded the condition “unthinkable.”

At one stage in his negotiation with the Russians, Chiang had expressed willingness to make two concessions: he would not allow a foreign power to use Chinese territory for anti-Russian bases and he would not form an anti-Russian alliance with a foreign power. The foreign power in question was implicitly the United States. But those concessions were far different from the proposition that he treat the United States as an enemy. In realpolitik terms, he could not trade the support of the United States, a decades-old ally, for an uncertain cooperation with Russia, a nation that had historically proven inimical to Chinese interests.

While seriously ill in June 1971, Chiang struggled to jot down in his diary his thoughts on foreign aggression—especially Russia’s—against China, and he reminded himself: “Today Russia is luring me to oppose the United States for the sake of fighting the Chinese Communists. I must never be tempted by it.”

Chiang had made up his mind not to exercise the Russia option.