- Law & Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

Frustrated by the failure to enact its pro-union agenda in Congress, President Barack Obama’s administration has unleashed its bureaucratic minions at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to achieve it through regulatory fiat. The core agenda is to reverse decades of eroding union membership by eliminating the right to secret ballot in union organizing.

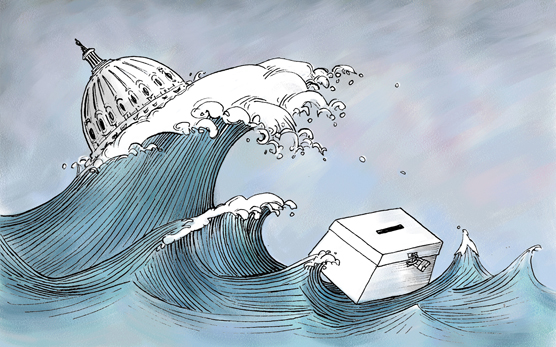

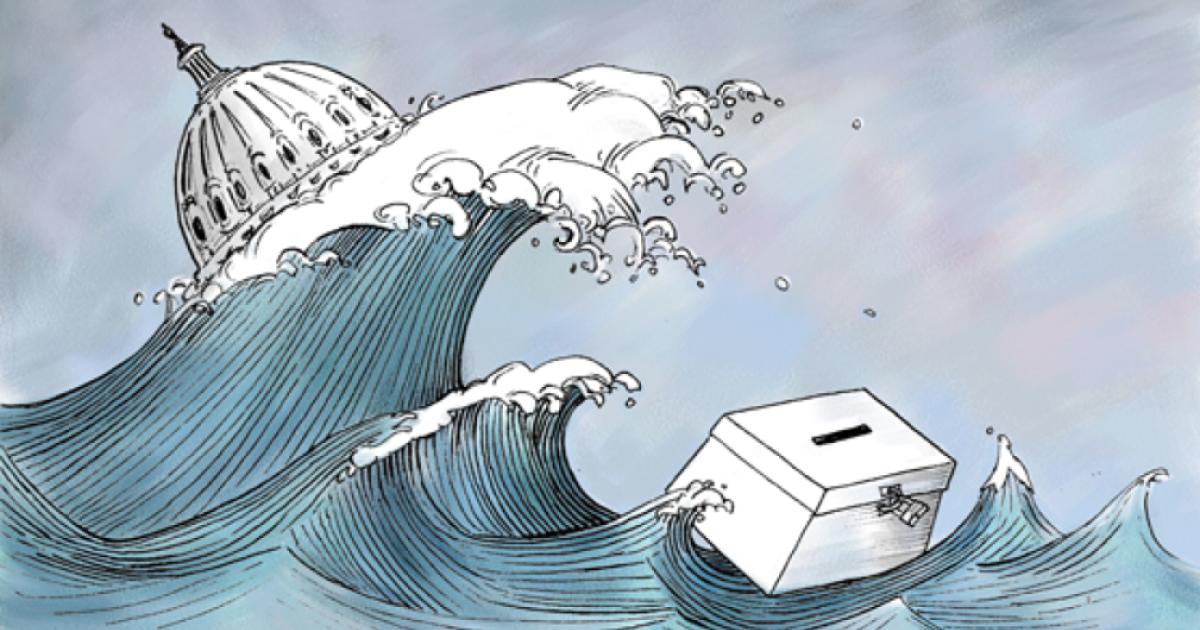

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

The NLRB’s latest salvo is a lawsuit against Arizona. Arizona is one of four states where voters last fall resoundingly added to their constitutions the right to secret-ballot elections in union organizing. The lawsuit is the most recent of many recent cases pitting state power against federal power. The outcome will determine in large measure the amount of individual autonomy Americans will enjoy in the years to come.

Jump-Starting Unions

Private-sector unionization has steadily plummeted since the 1950s, when roughly one in three private-sector workers belonged to a union. As of 2008, only 7.6 percent of private-sector workers were unionized. In 2010, that number fell further to 6.9 percent. Meanwhile, the number of unionized public-sector workers eclipsed those in the private sector for the first time in 2010, with close to eight million public-sector employees (or 37.4 percent) enrolled in unions compared to slightly more than seven million in the private sector.

It’s not that unions have ceased trying to organize private-sector businesses. It’s just that they are far less successful at doing so these days. Workers in American private industry increasingly recognize that the choice of union versus no union is not the difference between high and low wages, but often the difference between having jobs and no jobs. So given that choice, workers often reject unions.

Meanwhile, private-sector industries that are heavily unionized have a strong correlation with industries in economic decline. Having helped usher those industries into global uncompetitiveness, what are private-sector unions to do to avoid the fate of other dinosaurs?

Turn to the government, of course. If workers won’t freely choose to organize unions, take that choice away from them and substitute it with union thuggery.

That’s the idea behind "card-check," the labor union movement’s top legislative priority. Right now, if a specific percentage of workers at a business express support for a union, both employers and employees have the right to demand secret-ballot elections to determine whether a union is established. Card-check would change that to a system in which a union automatically is recognized if 50 percent of the workers sign cards requesting a union. Never mind if the person asking them to sign the card is a co-worker exerting peer pressure, much less a menacing bully.

Under federal law, the right to secret ballot has been the preferred method of union organizing for 75 years.

These secret-ballot elections are so important that when the Mexican government threatened to eliminate them in 2001, 16 Democratic members of the U.S. House of Representatives—including liberal luminaries such as U.S. Representatives George Miller (the principal sponsor of card-check), Bernie Sanders, Barney Frank, and Dennis Kucinich—wrote to defend "the secret ballot election in all union recognition elections." The representatives urged that "the secret ballot is absolutely necessary in order to ensure that workers are not intimidated into voting for a union they might not otherwise choose."

Indeed it is, and the right to secret ballot has been the preferred method of union organizing under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) for 75 years. Former U.S. Senator George McGovern chastised his fellow Democrats for abandoning it through card-check. "We cannot be a party that strips working Americans of the right to a secret-ballot election," he warned. "To fail to ensure the right to vote free of intimidation and coercion from all sides would be a betrayal of what we have always championed."

By all measures, most Americans emphatically agree. Concerned about the prospect of card-check, the Goldwater Institute drafted a proposed amendment called Save Our Secret Ballot, which would add to state constitutions or statute books the express right of workers to a secret-ballot election. Save Our Secret Ballot appeared on the 2010 ballot in four states—Arizona, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Utah—and passed overwhelmingly in each, with majorities ranging from 60 percent in Utah to 86 percent in South Carolina. It’s an issue that not only transcends the partisan divide, but the union divide as well: a 2004 Zogby poll found that 78 percent of union members favor the secret ballot.

This kind of opposition deterred even an overwhelmingly Democratic Congress from passing card-check. But President Obama was undeterred, promising the AFL-CIO he would "keep on pushing."

With legislative prospects derailed, the president turned instead to the NLRB, whose website proclaims its mission "to safeguard employees’ rights to organize and to determine whether to have unions as their bargaining representatives." It turns out that protection of worker choice no longer ranks very high in the NLRB’s pantheon of values.

The National Labor Relations Board: A Rogue Agency

In every administration, a handful of agencies tend to stand out as policy trailblazers. President Obama’s NLRB under chairman and former union lawyer Craig Becker surely earns that distinction.

Once Democrats solidified a majority on the NLRB, they set out to push a pro-union policy agenda that never could pass congressional muster. Earlier this year, NLRB fired a shot heard round the business world when it brought charges against Boeing, seeking to force it to abandon plans to open an assembly plant in South Carolina. Having had production curtailed by labor strikes in Washington State, Boeing wanted to diversify its operations to avoid future disruptions and to take advantage of the more favorable economic climate in South Carolina. Given Boeing’s painful experience, the decision made abundant business sense: South Carolina has the nation’s sixth-lowest rate of unionization (4.6 percent), compared to Washington, which has the fourth-highest (19.4 percent). Boeing’s decision will result not only in substantial labor-cost savings but also in greatly reduced threat of strikes.

Boeing is not abandoning its Washington operations—it has hired 2,000 workers there since 2009, compared to 1,000 in South Carolina—and the company even offered to promise not to lay anyone off. But that was not enough for the NLRB, which charged the company with illegal retaliation against its unions. The agency wants to force Boeing to abandon its South Carolina facility and locate it in Washington—an act that appears unprecedented in the NLRB’s history.

Save Our Secret Ballot appeared on the 2010 ballot in four states—Arizona, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Utah—and passed overwhelmingly in each.

The agency’s action is seismic. If successful, it would undermine economic competition among states, which helps drive the American economy. Even worse, it would induce companies to export jobs not to other states that have lower labor costs, but to other countries that do.

Refusing to Take No for an Answer on Card-Check

NLRB is playing an equally audacious role in pushing card-check. The agency recently announced it would reconsider its ruling in its 2007 Dana Corporation decision. That decision held that where a union was established without a secret-ballot election, workers could petition to decertify the union within 45 days. If the NLRB overturns the decision, it will destroy the principal protection workers have against involuntary unionization.

But the NLRB was only getting warmed up. In January of this year, it drafted letters to the attorneys general in the four states that passed Save Our Secret Ballot, demanding that they agree to not enforce the constitutional provisions. Mind you, card-check never passed, so the state provisions were not in conflict with federal law. The NLRB didn’t see it that way, concluding that because the National Labor Relations Act authorizes voluntary card-check union organizing, then establishing a right to secret-ballot elections clashes with federal law. But if workers object to union recognition by card-check, by definition it isn’t voluntary.

The attorneys general politely told NLRB to pound sand. In response, NLRB made good on its threat, filing a lawsuit against the Arizona measure and promising more challenges to come. Underscoring that the NLRB is not representing the interest of workers, the Goldwater Institute intervened to defend the law on behalf of dozens of workers in occupations ranging from nursing to teaching to construction.

The lawsuit raises important questions of federalism, which has come to the forefront of constitutional jurisprudence during the Obama era. The NLRB argues that under the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution, if federal and state laws collide, the latter must yield—that is, the state law is "pre-empted" by federal law.

But arrayed against the Obama administration’s interpretation of federal labor law are several powerful principles. First, states are free to give greater protection to individual rights than federal law. Second, the decision whether to join a particular group is protected by the freedom of association guaranteed by the First Amendment. Finally, courts will try their best not to find a conflict with federal law—an instinct that has greatly solidified in the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts.

In the central case regarding pre-emption under the NLRA, San Diego Building Trades Council v. Garmon (1959), the Supreme Court held that "state jurisdiction must yield" where activities are "plainly within the central aim of federal regulation." But "due regard for . . . our embracing federal system" compels the Court not to find pre-emption "where the regulated conduct touched interests so deeply rooted in local feeling and responsibility that, in the absence of compelling congressional direction, we could not infer that Congress had deprived the States of the power to act."

It is difficult to imagine an interest more deeply rooted in American democracy, both at the national and local level, than the right to secret-ballot elections. As the Court observed in a 1995 decision, the "tradition of anonymity in the advocacy of political causes . . . is perhaps best exemplified by the secret ballot, the hard-won right to vote one’s conscience without fear of retaliation." As former Chief Justice Warren Burger declared in Buckley v. Valeo, "the enlightened labor legislation of our time has enshrined the secrecy of choice of a bargaining representative for workers." Specifically, the courts have recognized that under the NLRA itself, secret ballots are "the most satisfactory—indeed the preferred method" of establishing union representation.

Despite the NLRB’s heavy hand, actions to protect the right to secret ballot at the state level proceed unabated.

In May 2011, the Supreme Court decided in Chamber of Commerce v. Whiting that Arizona’s employer sanctions law was not pre-empted because it promoted the objectives of federal law. The Court offered a strong presumption against federal pre-emption, which was especially noteworthy because the subject matter—immigration—is expressly entrusted to the federal government under the Constitution. That ruling is only the latest in a series of cases over the past decade in which the Court has brushed aside pre-emption claims in favor of state sovereignty.

A month later, the Court ruled in Bond v. United States that a woman could challenge a federal law under the 10th Amendment, which reserves to the states all powers not expressly delegated to the federal government. "Federalism secures the freedom of the individual," a unanimous Court ruled. "It allows States to respond, through the enactment of positive law, to the initiative of those who seek a voice in shaping the destiny of their own times without having to rely solely upon the political processes that control a remote central power." Those are exactly the values promoted by Save Our Secret Ballot.

Were it to succeed in its challenge, the NLRB’s action would reverberate beyond the private sector. Although the National Labor Relations Act encompasses most private-sector workers, states have jurisdiction over labor relations for state and local employees and agricultural workers. Already, at least six states (New York, Illinois, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Oregon, and Massachusetts) have adopted card-check rules for organizing workers subject to state jurisdiction. Such laws will fuel the growth of the public-sector unions that are bankrupting local governments across the United States. Save Our Secret Ballot amendments prevent adoption of card-check laws by other states—but the NLRB’s lawsuits could sweep those protections aside as well.

Political Tsunami

Despite the NLRB’s heavy hand, actions to protect the right to secret ballot at the state level proceed unabated. Already this year, Indiana and Tennessee have adopted statutory protections. Referenda and initiative efforts are underway for the 2012 elections in Missouri, Alabama, Michigan, Florida, California, and elsewhere.

President Obama cannot want to share a ballot with those measures on it. The right to secret ballot is a cornerstone of American democracy. It is difficult to imagine the proposed amendments failing anywhere. The proposition is simple and straightforward, and its equities unassailable. Yet this is the battle the Obama administration has chosen to fight.

By taking the issue to the courts, the NLRB hopes to remove it from the public discourse. Fighting pre-emption tends to be a titanic undertaking. The stakes, however, are worth it: protecting the right to secret ballot, thereby ensuring that union representation is truly consensual, and reining in an out-of-control federal agency that seems intent on inflicting grave harm upon American enterprise and competitiveness, and upon the rights of the very workers it is supposed to protect.