- Law & Policy

In Epic Systems v. Lewis, the United States Supreme Court held by a five-four vote last week that the individual contracts of non-union workers, which called for the arbitration of work-related disputes, were fully enforceable under the Federal Arbitration Act of 1925. In a variety of class actions, the Seventh Circuit had held that Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act overrode the FAA by explicitly guaranteeing—in addition to full-scale collective bargaining—the right to both union and non-union workers “to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid and protection.” The contention allowed workers who had signed individual arbitration agreements nonetheless to bring nationwide class actions under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, seeking overtime from employers who had misclassified their jobs.

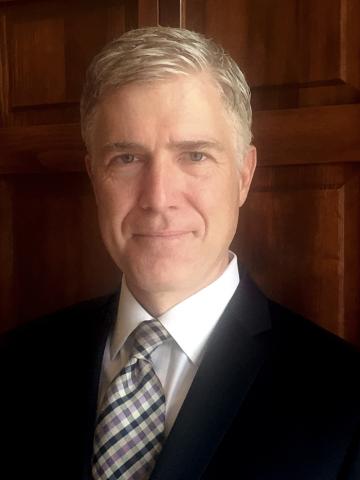

The harsh outcry in response to Justice Neil Gorsuch’s restrained and meticulous opinion makes it appear as if a retrograde Supreme Court has returned us to the harsh pre-New Deal days when avaricious employers routinely trampled on worker rights. In her bitter dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg denounced the majority opinion as “egregiously wrong” because it overlooked “the extreme imbalance once prevalent in our Nation’s workplaces” before the passage of the NLRA in 1935. As an illustration of this imbalance, she referred to the so-called “yellow-dog” contract, whereby an employee agreed not to join a union so long as he continued to work for his employer. A nasty New York Times editorial quoted Harvard Law Professor Noah Feldman to insist that only “if you lived on the moon” would you “imagine workers and employers negotiating under Marquess of Queensberry rules, engaged in a fair and equal face-off over working conditions.”

Justice Gorsuch is right on the law. Justice Ginsburg is wrong on both the law and the economics of these agreements.

Let’s start with the text of the FAA: A “transaction involving commerce to settle by arbitration a controversy thereafter arising out of such contract or transaction . . . shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.”

As Justice Gorsuch points out, this provision creates a strong presumption of enforcement that is only overridden by showing grounds in either law or equity for the revocation of any contract. The word “any” points to the proposition that the grounds for invoking this exception must apply across the board, and should not vary from contract type to contract type. In other words, courts can only disallow arbitration, in the words of the 2011 consumer arbitration case AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, under “generally applicable contract defenses, such as fraud, duress, or unconscionability.” It is worth noting that the purported illegality of the contracts at issue under the FLSA is not a ground to revoke any contract, but a ground that can be presented to the arbitrator to explain why it should be unenforceable. Revoke the arbitration clause and then no dispute can be arbitrated.

Under Justice Ginsburg’s dissent, any two or more workers may always challenge an employer’s behavior in federal court under the aegis of the NLRA, even when there is no union. Justice Ginsburg defends her position by pointing to such decisions as Brady v. National Football League (2011), in which the NFL players union disbanded temporarily in order to bring an antitrust action against the NFL to break a bargaining impasse. Justice Gorsuch rightly invoked the statutory canon of ejusdem generis—the statute only covers matters “of the same kind”—to stress that the activities covered by the concerted action clause should, as in Brady, be connected to organizing activities, and not a vehicle for pressing individual grievances through the class action device.

As Justice Gorsuch noted, his position was in fact held by the National Labor Relations Board until it was reversed by the Obama-appointed Board in 2012. The sudden flip-flop of the Obama administration offers yet another justification for Gorsuch’s steadfast opposition to judicial deference to agency decisions under the Court’s oft-questioned 1984 decision in Chevron v. NRDC. It is bad enough to let an agency unilaterally expand the scope of its own powers. It is worse to let it interpret a statute outside its purview, which is what the NLRB sought to do here.

Employers clearly do not share Justice Gorsuch’s neutrality on the policy wisdom of individual arbitration clauses. Instead, they have been adopting those clauses in droves. The question is why? For Justice Ginsburg, the answer lies in a bleak vision of how labor markets worked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries before the passage of the NLRA and FLSA. “Under economic conditions then prevailing,” she writes, “workers often had to accept employment on whatever terms employers dictated.” To overcome this disadvantage, “employees must have the capacity to act collectively in order to match their employers’ clout in setting terms and conditions of employment.” Indeed, Justice Ginsburg sees in mandatory arbitration clauses a revival of the dreaded “yellow dog” contract that leaves “the laboring man . . . absolutely helpless” in dealing with his or her employer.

Justice Ginsburg’s so-called realist account lacks empirical support. In his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, the economist Robert Gordon reports that the greatest economic growth ever seen in the history of the world occurred in the United States between 1870 and 1940. But what he does not note is that this growth took place—no coincidence, I believe—during the period in which the Supreme struck down, in Adair v. United States (1908) and Coppage v. Kansas (1915), federal and state legislation that authorized the mandatory system of collective bargaining. The New Deal Supreme Court reversed course, and wrongly upheld these in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel (1937). As the two earlier cases recognized, the greatest protection for any given worker is a competitive market in which employers have to compete for workers by offering terms that work to the mutual advantage of both sides. The take-it-or-leave-it approach is properly used in all markets for goods and service. Otherwise, bargaining becomes a pointless charade until one side or the other coerces its trading partner into an unwanted deal.

The NLRA, routinely hailed as “the Magna Carta of American labor,” only creates a a state-sponsored labor cartel that would be per se illegal if Section 6 of the Clayton Act (1914) had not exempted labor unions from the antitrust laws. Ordinary cartels raise costs of contracting; they reduce output; and they raise prices. Labor cartels are even worse. They open up the risk of bargaining breakdown, as well as strikes and lockouts that disrupt commerce. Labor cartels are especially bad because they lead to racial discrimination, featherbedding, senior protection, and other inefficient practices that could never survive in competitive markets.

In this setting, the much reviled yellow-dog contract upheld by Justice Pitney in Hitchman Coal v. Mitchell (1917) performs, as I have long argued, a vital social function by preventing unions from obtaining agreements that allow them, unannounced, to call strikes that cause maximum disruption in mines and mills. By letting employers sue unions for the intentional interference these labor contracts allow, the yellow-dog contract helped preserve competitive conditions in labor markets, by putting pressure on unionized firms to lower prices and thus improve overall social welfare.

Justice Ginsburg, the New York Times, and Noah Feldman do not address the public policy defense of the yellow-dog contract. Indeed, even Justice Gorsuch is a bit wobbly on this issue, when—with a conservative nod to judicial restraint—he agrees with the liberals that Congress should have full power to regulate labor markets by blessing inefficient cartels. But individual liberties in various businesses and occupations deserve as much protection as those for religion and speech. This is precisely the logic behind the yellow-dog contract—and it explains why employers of all sizes and in all markets harbor such a visceral hostility toward class action litigation. Class action suits do not restore any imagined state of equality between employers and employees. Rather, they let class action lawyers impose enormous litigation and liability costs on employers—so much so that once a class is certified, employers have to settle quickly in order to escape potential financial ruin. Ex ante, employees know that signing a waiver of arbitration provision redounds to their benefit: the smaller the liability threat ex post, the higher the base wages, and the greater job opportunities and security.

Right now, Epic Systems sets the balance in the right place. Unfortunately, under current law, Congress could easily amend the FAA to allow an endless stream of class actions that will once again stifle job growth and wage increases. Labor shortages spark intense recruitment and better job offers. Ham-handed government interference does the opposite. The best way to keep the markets in sync is to do the unthinkable: return to the constitutional regime of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which protected competitive labor markets and spurred unprecedented economic growth.