- Education

- K-12

In a globalizing economy, America’s competitive edge depends in large measure on how well our schools prepare tomorrow’s workforce.

And notwithstanding the fact that Congress and the White House are now controlled by opposing parties, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are bent on devising new programs and boosting education spending.

Consider the America Competes Act—signed into law in August— which substantially increases government funding for science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). This bipartisan initiative is supported by President Bush and Education Secretary Margaret Spellings, as well as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. Nearly all the 2008 presidential candidates endorse its goals. And 38 state legislatures have also recently enacted STEM bills.

Indeed, STEM has swiftly emerged as the hottest education topic since No Child Left Behind. They’re related, too. NCLB puts a premium on reading and math skills and also pays some attention to science. Marry it with STEM and you get heavy emphasis on a particular suite of skills.

But there is a problem. Worthy though these skills are, they ignore at least half of what has long been regarded as a “well-rounded” education in Western civilization: literature, art, music, history, civics, and geography. Indeed, a new study from the Center on Education Policy says that, since NCLB’s enactment, nearly half of U.S. school districts have reduced the time their students spend on subjects such as art and music.

This mistake ill serves our children and misconstrues the true nature of American competitiveness and the challenges we face in the twenty-first century.

BEYOND THE BASICS

As with all education reforms, the STEM-winders mean well. They reason that India and China will eat America’s lunch unless we boost our young people’s prowess in the STEM fields. But these enthusiasts don’t understand that what makes Americans competitive on a shrinking, globalizing planet isn’t outgunning Asians at technical skills. Rather, it’s our people’s creativity, versatility, imagination, restlessness, energy, ambition, and problem- solving prowess.

True success over the long haul—economic success, civic success, cultural success, domestic success, national defense success—depends on a broadly educated populace with flowers and leaves as well as stems. That’s what equips us to invent and imagine and grow one business line into another. It’s also how we acquire qualities and abilities that aren’t easily outsourced to Guangzhou or Hyderabad.

Students who garner high-tech skills may still get undercut by people halfway around the world who are willing to do the same work for onefifth of the salary. The surest way to compete is to offer something the Chinese and Indians (and Vietnamese, Singaporeans, and so on) cannot—technical skills are not enough.

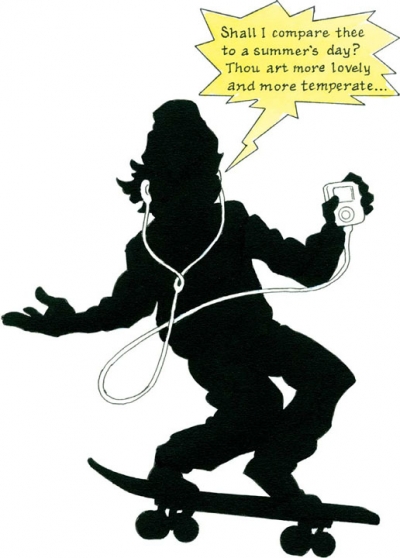

Apple’s iPod was not just an engineering improvement on Sony’s Walkman. It emerged from Steve Jobs’s American-style understanding of people’s lifestyles, needs, tastes, and capacities. (Yes, Mr. Jobs dropped out of college—but went on to study philosophy and foreign cultures.)

Pragmatic folks naturally seek direct links from skill to result, such as engineers using their technical knowledge to keep planes aloft and bridges from buckling. But what about Abraham Lincoln educating himself via Shakespeare, the Bible, and other great literary works? Alan Greenspan’s degrees are in economics, but he plays a mean jazz saxophone. Indeed, many of today’s foremost (and wealthiest) entrepreneurs, people such as Warren Buffett, studied economics—not a STEM subject—in college. Adam Smith studied moral philosophy.

CORE VALUES

The liberal arts make us “competitive” in the ways that matter most. They make us wise, thoughtful, and appropriately humble. They help our human potential to bloom. And they are the foundation for a democratic civic polity, where each of us bears equal rights and responsibilities.

History and literature also impart to their students healthy skepticism and doubt, the ability to ask both “why?” and “why not?” and, perhaps most important, readiness to challenge authority, push back against conventional wisdom, and make one’s own way despite pressure to conform. (How will that be viewed in China?)

We’re already at risk of turning U.S. schools into test-prepping skill factories where nothing matters except exam scores on basic subjects. That’s not what America needs, nor is it a sufficient conception of educational accountability. We need schools that prepare our children to excel and compete not only in the global workforce but also as full participants in our society, our culture, our polity, and our economy.

Addressing a recent Fordham Foundation education conference, National Endowment for the Arts chairman Dana Gioia said, “We need a system that grounds all students in pleasure, beauty, and wonder. It is the best way to create citizens who are awakened not only to their humanity, but to the human enterprise that they inherit and will—for good or ill— perpetuate.”

Creating such a system calls not for a host of specialized new institutions and government programs but for closely examining the curriculum in all our schools. It also calls for recalibrating academic standards and graduation requirements, as well as amending our testing-and-accountability schemes—most certainly including NCLB—by widening the definition of “proficient” to include reasoning, creativity, and knowledge across a dozen subjects as well as basic cognitive skills. We need to start reconceptualizing “highly qualified“ teachers as people who are themselves broadly educated rather than narrowly specialized.

Abandoning the liberal arts in the name of STEM alone also risks widening social divides and deepening domestic inequities. The well-to-do who understand the value of liberal learning may be the only ones able to purchase it for their children. Top private schools and a few suburban school systems will stick with education broadly defined, as will elite colleges. Rich kids will study philosophy and art, music and history; their poor peers will fill in bubbles on test sheets. The lucky few will spawn the next generation of tycoons, political leaders, inventors, authors, artists, and entrepreneurs. The less lucky masses will see narrower opportunities. Some will find no opportunities at all, which frustration will tempt them to prey upon the fortunate, who in turn will retreat into gated communities, exclusive clubs, and private this-and-thats, thereby widening domestic rifts and worsening our prospects for social cohesion and civility.

Not a pretty picture. Adding leaves and flowers to STEM and NCLB won’t necessarily avert it—but hewing to basic skills at the expense of a complete education will surely worsen it.