- World

- Campaigns & Elections

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

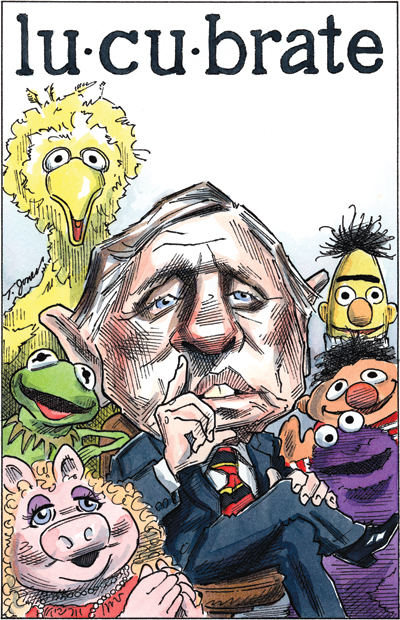

It was the longest-running program in the history of television. Firing Line was on the air from 1966 until Bill Buckley himself brought it to a close in 1999—“the end of the millennium,” he said, “kind of makes sense.” His opus included 1,500 episodes—all accompanied by Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2, the same lively counterpoint performed April 5 at Buckley’s public memorial in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. How did a cerebral program devoted to policy and culture set such an unlikely record?

Twice a guest on Firing Line, I sat in the control room during several tapings and, helping Buckley edit On the Firing Line, his 1988 book about the program, pored over hundreds of transcripts. Here is what I learned.

As a guest: Before the cameras rolled, Buckley would offer his interview subjects a moment or two of small talk, not a briefing. And although he would have looked over a stack of research, he would have committed to his clipboard only a few notes, not a detailed outline or script. When he received his cue, Buckley would swivel to the camera to read his introduction, the one item he would always have typed word for word, and then swivel to you to ask the first question. You would reply as best you could. And then? He would spend the rest of the hour making it up.

Spontaneity, freshness, unpredictability: Buckley was to television what Louis Armstrong was to the trumpet—the master of sustained improvisation.

In the control room, watching Buckley from different angles on an array of screens, you were struck by how totally he commanded the frame. The blue eyes, the slouch, the boyishly disarrayed hair, the crooked grin, the way his gaze seemed to drift into the middle distance, then suddenly pinion his guest—all proved visually enthralling. If he had been born in the nineteenth century, when print remained the only medium, or come of age during the first several decades of the twentieth century, when radio was ascendant, Buckley would still have attained fame. But his gifts fit television precisely. In giving Bill Buckley to us when it did, Providence knew what it was doing.

Editing On the Firing Line: It has been two decades since I worked with Buckley on that book, but I still recall realizing that the secret of Firing Line lay in a paradox. On the one hand, Buckley approached Firing Line with a sense of high purpose. Whatever other intellectuals may have thought about the medium, he believed that television could offer instruction and inspiration. On the other hand, he could hardly have taken more pleasure in Firing Line had it been a sporting event. Norman Mailer, Muhammad Ali, Milton Friedman, Margaret Thatcher, John Kenneth Galbraith—Buckley clearly reveled in his encounters with each. One evening we watched a tape of Buckley’s 1976 debate with Ronald Reagan about the Panama Canal. Buckley offered a running commentary, his face alight with pleasure, noting how Reagan, in so many ways his opposite—so plainspoken and so apparently unsophisticated—had nevertheless proven so effective. “Ronnie,” Buckley said, chuckling with admiration, “was good.”

For 33 years, Firing Line permitted Americans to watch a great man having serious fun.