- History

As the Preamble to the 1957 Treaty of Rome stated, the purpose of the then European Economic Community was to “lay the foundations of an ever-closer union” among Europeans. This phrase became interpreted as a call for a progressively tighter political merger of the member states, with the European Union as the latest embodiment of this purpose. The problem with this progressive vision, however, is twofold: first, it is never fully achieved as the final objective remains always on the horizon and, second, it is grounded in the belief that a common market can create a unified polity. As a result, the EU is always in trouble because it is a perennially unfinished product built on weak foundations. It is a frustrated empire.

The various crises of recent months—Brexit, continued Chinese economic predation, and the surprising pandemic—only exacerbated these fundamental problems of the EU. Brexit, driven in part by the British unwillingness to continue toward a misty “ever-closer union,” has shaken the faith of European elites in the historical inevitability of this European project. Moreover, it has altered the balance of power inside the EU, removing a key ballast in the delicate dynamics of European politics: Germany is much more difficult to check now. At the same time, many European countries, fiscally constrained by the rules of the eurozone, have grown more dependent on Chinese investment, while across the continent China has become one of the top economic partners (for Germany it is the number one trading partner). Finally, the pandemic has devastated most economies, with a particularly dramatic effect in those states, such as Italy, that had never recovered from the 2008 economic crisis and are at risk of defaulting on their debt. The collapse of the Italian economy, which is ten times larger than that of Greece, would most likely result in an “Italexit” and end the European Union.

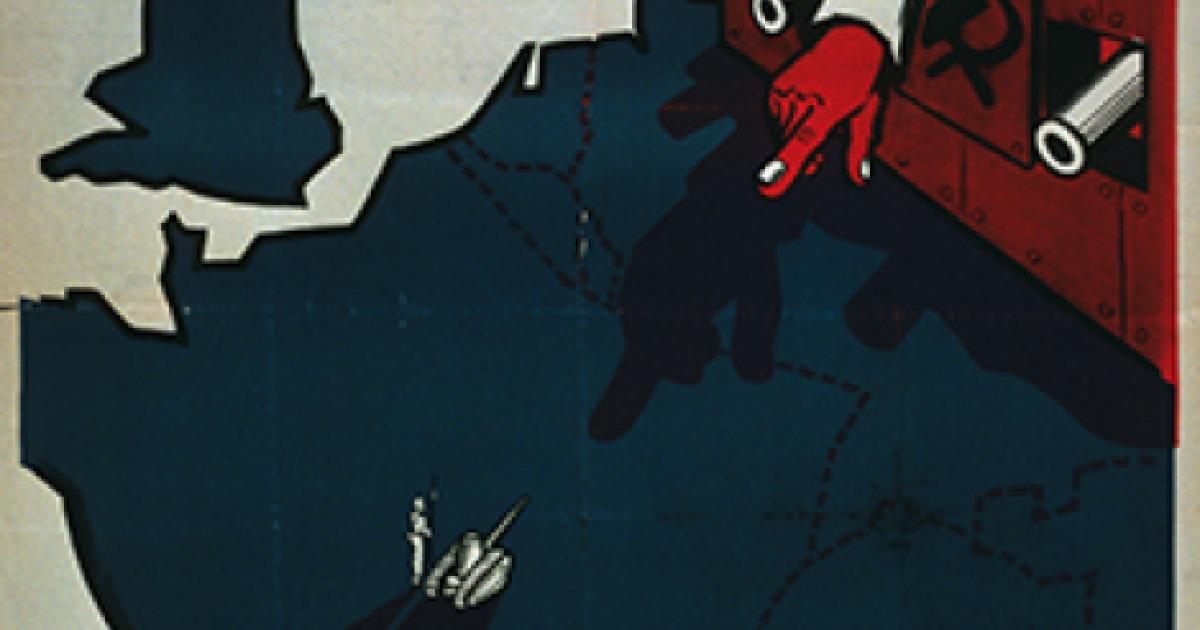

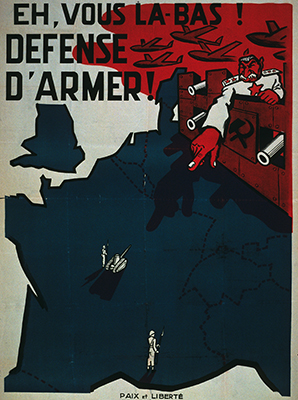

These challenges are compounded by the continued presence of external threats (Russia in the east and the south, the migration crisis from North Africa) and domestic tensions (high unemployment in the Mediterranean countries, social tensions with immigrants). There are no easy solutions to these problems, of course. But the European political elites adopt the same strategy for all of them: more union and more economic centralization. That is, they use every crisis to take another step toward that “ever-closer union” built on monetary and, increasingly, fiscal unity.

The boldest move was in response to the economic mess caused by the pandemic. EU leaders agreed to a relatively modest relief package backed by bonds guaranteed, for the first time, by the Union as a whole rather than individual countries. This allows countries like Italy to get funds at a considerably lower rate, and diminishes the risk of their default. The relief package is more relevant, therefore, for how it is financed than for its size—another sign that EU leaders use economic tools for their political goal of creating a supranational EU. It’s all about politics, not economics: the package will do little to help the beleaguered economy of Italy but it will advance surreptitiously the establishment of a central EU authority in control of not just the monetary but also fiscal policies of states.

Membership in the eurozone means already that states, such as Italy, have no control over monetary policies (e.g., they cannot print money and devalue their currencies in time of massive economic downturns) and are constrained in their fiscal behavior (e.g., they are not supposed to exceed certain deficit-to-GDP ratios). But the goal has always been to remove completely fiscal decisions from the national governments and allow a central EU body to make these decisions. Bonds guaranteed by the EU as a whole will lead naturally to the next step: an EU-wide tax of some sort and a growing fiscal power of the Bruxelles to the detriment of individual capitals. National parliaments and leaders, so the belief goes, cannot be trusted with fiscal policies for their own countries, and it is safer to let experts at the EU level make these decisions for the good of the Union as a whole. So much for national democracies.

Beyond the disregard for democratic legitimacy, such a vision is grounded in a mistaken set of assumptions suggesting that economic unity will create a unified demos. But the same way that a joint checking account does not create a marriage, a centralized fiscal and monetary apparatus will establish no European nation and polity. The line of causation behind the EU project is simply wrong. Political cohesion arises out of national solidarity and a common sense of purpose, not out of sharing the same coin or having a centralized tax authority.

None of the recent crises, therefore, has altered the EU political elites’ progressive vision or their faith in the transformative power of a Europe-wide monetary and fiscal authority. The solution to the current challenges creates conditions that guarantee internal crises down the line. The EU is thus a frustrated empire: under pressure from within and from without, governed by political leaders insouciant about the democratic illegitimacy of their decisions, unable to secure their own borders and stabilize their immediate neighborhood, and in constant search of greater control over their member states. The outcome is that there will be growing tensions between the EU apparatus and its member states (or at least some national leaders eager to preserve political legitimacy and national freedom). The euro will not collapse anytime soon and the EU will continue to muddle through, but its underlying problems remain unaddressed. The frustrations of the EU are structural, stemming out of the very nature of this political entity, and are not just passing tribulations tied to the geopolitical ups and downs of Eurasia.