- History

We’ve heard it before—the tank is dead. The first time I read this statement was in the early 1980s, when an article in a major national newspaper trumpeted the results of the testing of the M712 Copperhead, a 155mm cannon-launched guided projectile with the capability to destroy a tank with a single round. As a soon-to-be commissioned armor officer, this assertion was of no small concern to me. I needn’t have worried. Twenty-six years later, after a full career that included having commanded a tank brigade in combat in Iraq, I retired from the U.S. Army, and the tank was still very much alive. The Copperhead round, now relegated to military museums, hadn’t killed it. Neither had the TOW anti-tank guided missile, the Hellfire, or more recently, the Javelin or suicide drones. Sure, these weapons have piled up an impressive record of armored vehicle destruction, but commanders—most recently, Ukrainian—still clamor for tanks when close combat is involved.

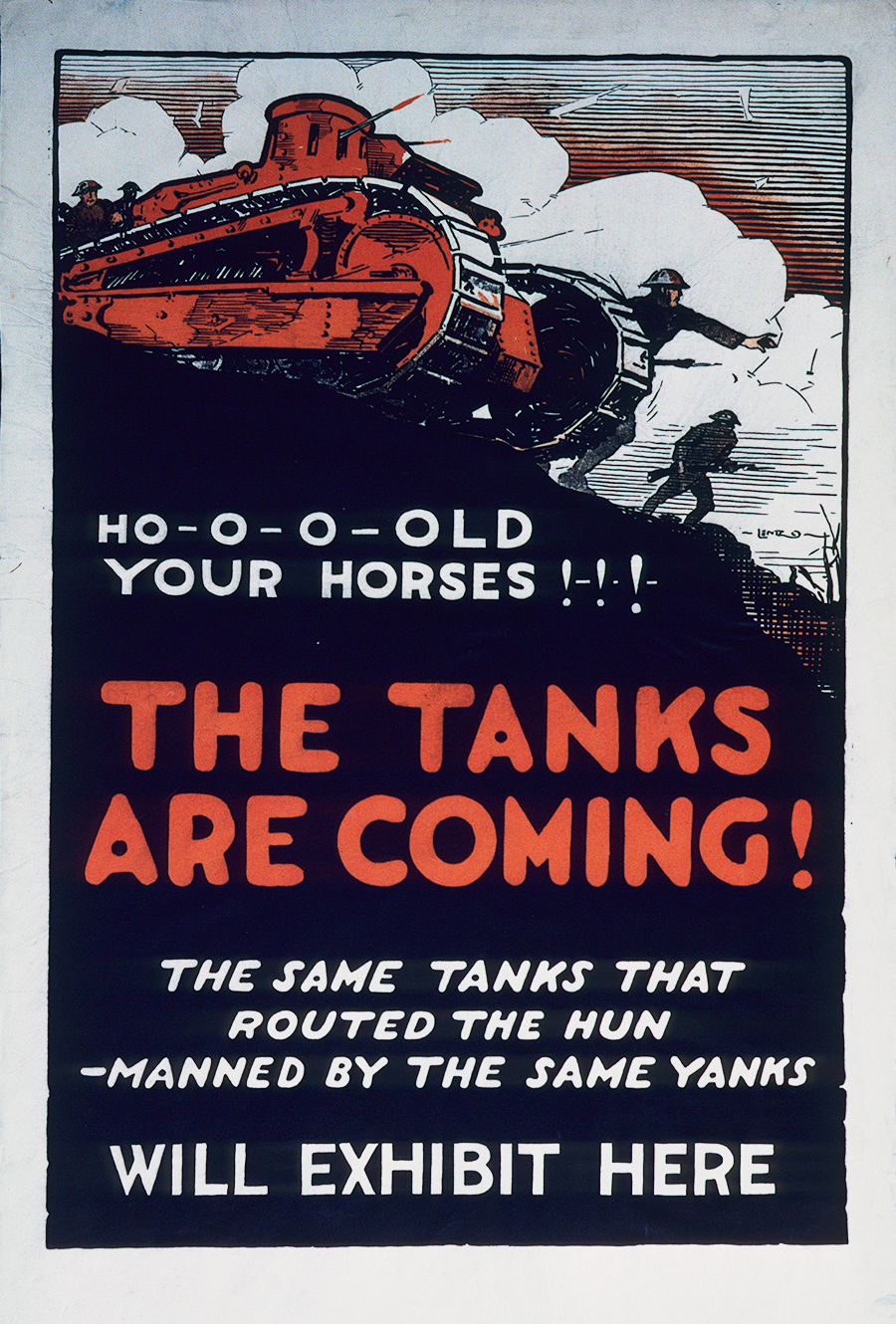

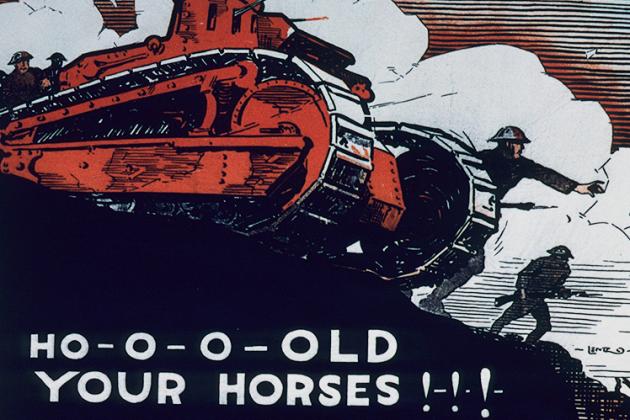

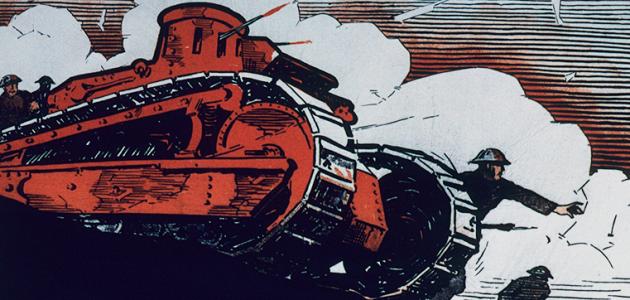

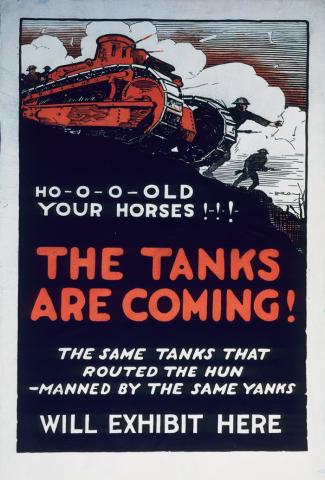

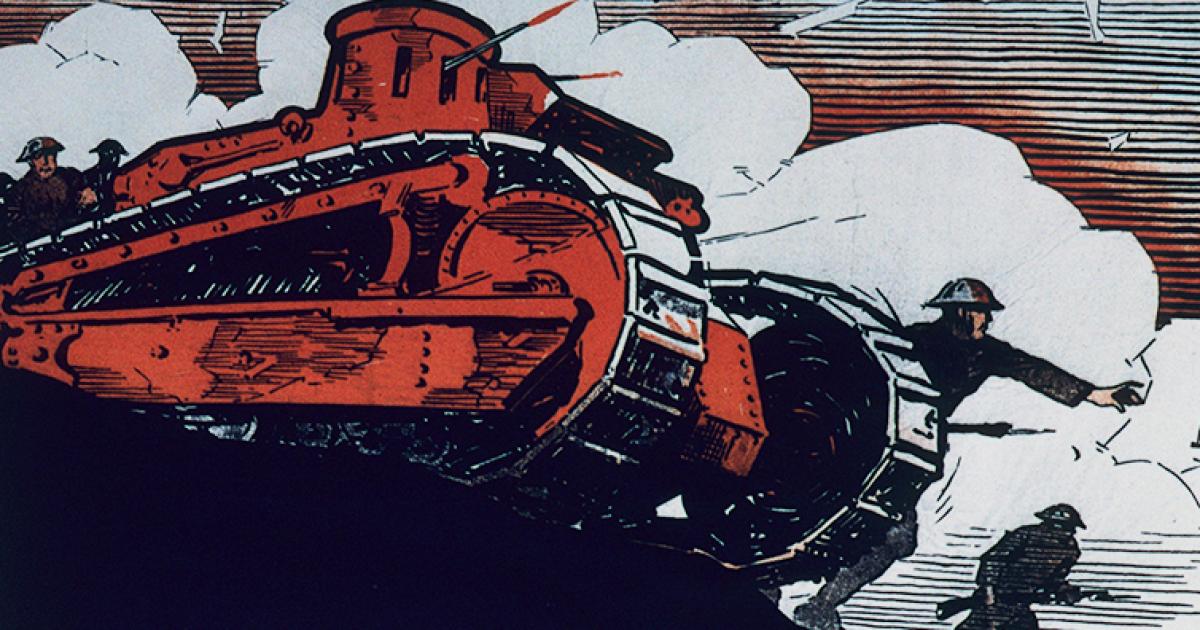

The reason is not hard to divine. When crossing the deadly ground that separates one army from another, it is better to be protected by an armored envelop than not. Tommies, Poilus, Doughboys, and soldiers from other nations learned this the hard way during the First World War by dying by the millions in an often heroic but vain attempt to negotiate no-man’s land protected by little more than a steel helmet and a cloth uniform. As early as 1914, both the French and British militaries drew up conceptual plans and then experimented with armored tractors to cross the killing zone. The British Army was the first to field production vehicles, with thirty-two tanks participating in the initial engagement on the Somme battlefield in September 1916. Of these, only nine made it across no-man’s land to German lines. But there they were, impervious to artillery splinters and bullets, and capable of negotiating barbed wire entanglements and enemy trenches. The promise of armored warfare had been born.

Fourteen months later at the Battle of Cambrai, 437 tanks supported an attack by six British infantry divisions that succeeded in penetrating the vaunted Hindenburg Line before stalling out due to lack of follow-up and German counterattacks. The tanks of the Great War were vulnerable to even rudimentary anti-tank weapons and were mechanically unreliable, but far-sighted theorists saw in them the solution to the deadlock of trench warfare. Improved tank models appeared in 1918. Hundreds of tanks were used in each of the major Allied offensives that year. During the Battle of Amiens on August 8, 1918, six hundred tanks supported the British, Canadian, and Australian attack that shattered German forces in what General Erich Ludendorff called “the Black Day of the German Army.” Prospective offensives in 1919 would have involved thousands of tanks, but the Armistice ended the conflict before they were needed.

What perceptive theorists learned from these experiences was tanks alone were vulnerable to anti-tank guns and artillery but tying tanks to the pace of infantry failed to take advantage of the mobility of armored vehicles. The forthcoming revolution in military affairs—a discontinuity in military operations created by new technologies, doctrine, and organizations—was the creation of a mounted combined arms formation that paired tanks with mechanized infantry, artillery, engineers, and air defense assets, and supported overhead by fighters to gain and maintain air superiority and provide close air support when needed. The British Army experimented with such a force on Salisbury Plain in 1927–28, but lack of funding retarded tank design and British leaders suspended the experiments. Soviet experiments were likewise promising until Stalin’s purges killed off most of the innovators in the mid to late 1930s. The French Army, which had fielded more tanks than any other army in the Great War, instead put its faith in an artillery-centric “methodical battle,” epitomized by the Maginot Line, a 280-mile long line of fortifications and obstacles along the Franco-German frontier.

Ironically, the German Army, denied tanks by the Treaty of Versailles, conducted the most advanced conceptual work on combined arms armored operations. Much of this work was done in secret in Russia in collusion with the Red Army, until Hitler’s rise to power ended weapons development cooperation with the Communist state. The creation of panzer divisions proceeded as German rearmament in violation of the Treaty of Versailles accelerated. Poland succumbed in just four weeks in September 1939, the Polish Army bulldozed by the German Army from the west and the Red Army from the east. Given the vast numerical and technological disparity between the Poles and their enemies, that result was unsurprising to informed military analysts. But what came next shocked the world.

In just six weeks in May and June 1940, the Wehrmacht shattered the French Army and its British, Belgian, and Dutch allies. The Germans employed eight of their ten panzer divisions in a surprise attack through the Ardennes Forest and across the Meuse River, destroying the French Second and Ninth Armies. Gen. Heinz Guderian then directed his XIX Panzer Corps in a drive to the Channel coast, cutting off allied armies in northern France and Belgium. The evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk followed, and with it any chance of saving France. The rest of the campaign was a forgone conclusion. Armored warfare—or “blitzkrieg,” as it was dubbed by Western journalists—had come of age.

As with any revolution in military affairs, it was only a matter of time before other militaries caught up to the Germans. The Soviets were caught unprepared for the 1941 German invasion, Operation Barbarossa, but had some surprises of their own in new tank models such as the T-34 and the KV-1 heavy tank that outclassed their German opponents. The Germans responded by upgunning their Mark III and Mark IV tanks and then, with further tank development, with Panther and Tiger tanks appearing on the battlefield in 1943. Tank armor and armament became thicker and more lethal in tandem with the introduction of larger anti-tank guns and hand-held anti-tank weapons, such as the Panzerfaust and the bazooka, featuring shaped charge warheads. The Soviet, British, and American armies all created armored divisions that were more than a match for their German counterparts, especially when combined with potent close air support. As allied armies rolled into Germany in the spring of 1945, armored forces ruled the battlefield.

For a quarter century after the end of World War II, nothing much happened to challenge the dominance of armored forces on the battlefield. Israeli armored operations overwhelmed Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian forces in 1956 and again in 1967. The Yom Kippur War of 1973, however, witnessed the introduction of wire guided anti-tank missiles. Israeli tanks impaled themselves on Egyptian anti-tank defenses until Israeli commanders relearned the basics of combined arms warfare—that tanks alone are vulnerable on the battlefield unless used in concert with other arms and services. With that lesson relearned, Israeli armies went on to defeat their adversaries, conquer the Golan Heights, and cross the Suez Canal into Africa.

The advent of guided munitions in the 1970s and 1980s threatened the dominance of the tank and armored vehicles on the battlefield. The advent of the Copperhead artillery round was a part of this development. But tanks and armored vehicles are only vulnerable if they lack protection. As the lethality of anti-tank weapons has increased, so has the effectiveness of tank armor and armament in an action-reaction-counteraction cycle that continues to this day. Composite armor, reactive armor, and active protection systems have proven effective against many anti-tank weapons. Laser range finders, thermal sights, and larger main guns have increased the killing power of tank armament. The result has been devastating for armies on the losing end of the technological equation. With air supremacy to protect them from attack, U.S. and coalition armored forces destroyed the Iraqi Army in Kuwait and Iraq in 1991 and again in 2003.

What the world is witnessing in Ukraine today is not the end of the tank, but rather the latest chapter in the continuing development of armored forces. Soldiers require mobile, protected firepower to close with and destroy the enemy. The alternative is a return to trench warfare, which is happening in the Donbas region and southern Ukraine today. Offensive operations require mobile, protected firepower—in a word, tanks. That is why Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has pleaded for tanks from the West. His army cannot conduct mobile, combined arms warfare without them. But tanks alone are not the answer—and they never have been. Rather, the answer to crossing the killing zone is the same as it has been since 1918—the use of armored, combined arms forces that are protected from those weapons that are lethal against them. Air defense forces, counter-drone systems, and anti-mine technology are crucial to ensuring the survival of armored forces on the battlefield. When armored forces are protected from these threats, they remain what they have been since the Battle of Cambrai in 1917—the king of the killing zone.