- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

Opposition to the Iraq war has understandably led to an anti-interventionist climate in Washington. There has long been such a strain in American public opinion: Walter Russell Mead identified it as the Jeffersonian strain, more interested in cultivating the American garden than in going abroad to slay dragons.

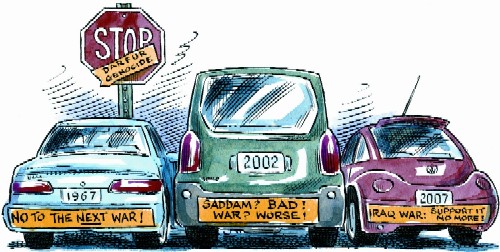

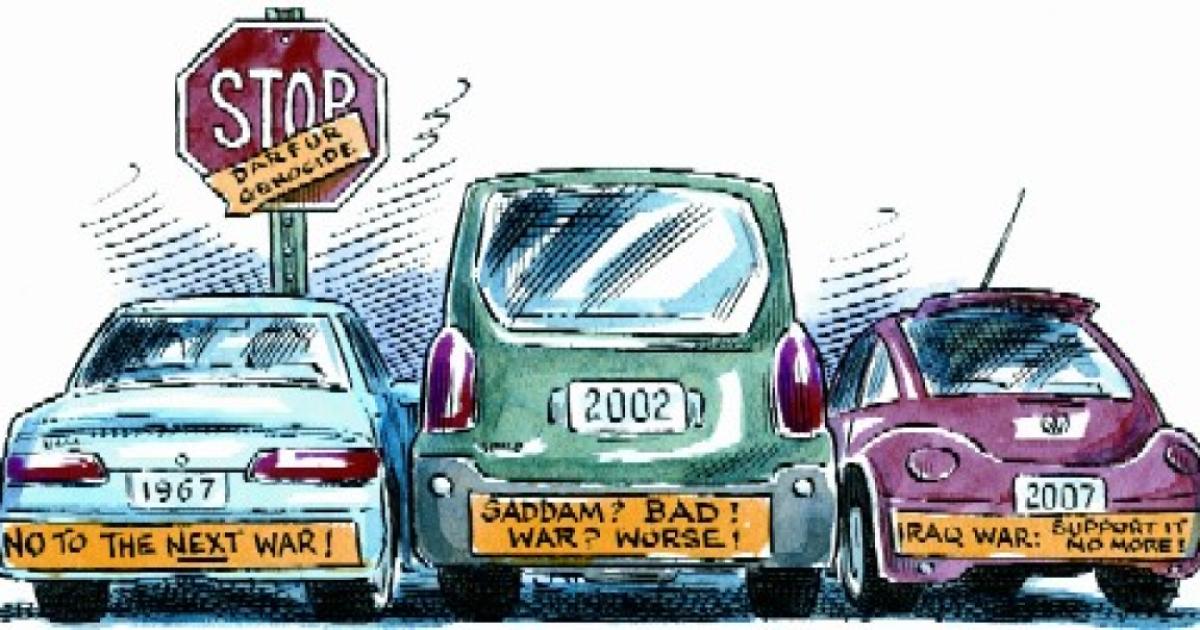

A bumper sticker I saw recently captures the spirit: “I’m already against the next war.” Of course, it’s unlikely that the experience in Iraq is what led the car’s owner to that conclusion. It was almost certainly a preexisting conviction. The opposition to the Iraq war has, however, inflated this sentiment.

Opposition to the Iraq war belongs in three broad categories: those who were against it from the beginning because of a principle like that of the bumper sticker; those who were against it not out of a general anti-interventionist sentiment but because they viewed Saddam Hussein’s regime as not dangerous enough to justify war; and those who supported the war at the time but have since decided that it wasn’t worth the effort. Those three categories together make up the clear majority in opinion surveys. But the third category, by far the largest, is actually quite different in outlook from the first two. In relation to Iraq at the present moment, it is aligned with the others, but there is little reason to think that this is a permanent alignment.

In December, the Genocide Intervention Network released a poll on Darfur that illustrates how far American opinion is from supporting a general disengagement from the troubles of the wider world. The Darfur case is important in its own right, because of the hundreds of thousands of people who have died at the bloody hands of the Sudanese government and its local death squads, the janjaweed militia, and the millions who are living in displaced-person or refugee camps in Sudan and Chad, unable to return to what’s left of their homes because of the danger. It’s also important as a test of American sentiment on humanitarian intervention.

The United States has no “vital interests” in Sudan or, for that matter, traditionally construed “national interests” that would lead to any kind of action whatsoever in support of the people of Darfur. Indeed, the problem runs the other way, because of an apparent intelligence-community fascination with the supposed cooperation from the Sudanese government on intelligence matters. China, meanwhile, which buys 80 percent of Sudanese oil exports, has been outspoken in defense of the “sovereignty” of Sudan. Insofar as the U.S. government has a broad range of important issues with China, Darfur has a lot of competition for a priority slot among them.

In short, one could easily walk away, or avert one’s gaze, and leave the fate of a couple of million distant people to themselves. Except that that is not the opinion Americans express on the subject.

First, they do indeed regard genocide in Darfur as their business, not an “internal affair” of Sudan into which we should not meddle. Sixty-two percent of Americans rate dealing with a humanitarian crisis such as genocide a top priority (19 percent) or a high one (43 percent), whereas only 14 percent call it a low priority or no priority at all. (Twenty percent rate it as medium.) Fifty-nine percent of adults and 65 percent of voters surveyed say they have heard a lot or some about the situation in Darfur. The realpolitik argument is a loser: sixty-three percent support “freezing assets of Sudanese leaders even if they occasionally provide information to the United States on Al-Qaeda activity.” Fifty-four percent would ban tankers carrying Sudanese oil from U.S. ports.

The survey asked about a cruise-missile attack to take down the Sudanese air force, and the answer was no, 59 to 32 percent. But that’s not a result that indicates only an arm’s length willingness to respond to the crisis in Darfur: by 50 to 44 percent, respondents supported “putting U.S. troops on the ground in Darfur, as a small part of an international peacekeeping force.” And when Americans are asked whether they would support sending 10,000 U.S. soldiers to Sudan on an “aggressive peacekeeping mission that may cost more than 100 U.S. lives” if that’s the only way to halt the violence, what’s astounding is not the 58 percent who said they would oppose such unilateral action but the 37 percent who said they would support it.

Of the 44 percent who oppose U.S. participation in a multilateral peacekeeping mission, 24 percent say they are strongly as opposed to somewhat against it. Let’s take that 24 percent as a proxy for the percentage of Americans who are “already against the next war.” And then let’s look at that 37 percent who would support unilateral military action: it looks as if the percentage of those who are already in favor of the next war is higher, at least if that’s the only thing that will stop genocide.