- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

During the cold war, the U.S. embassy in Moscow occasionally released an end-of-the-year cable to break up the usual routine of political assessments and military analyses. Instead, it quoted the latest jokes making the rounds of Moscow. A sample: Leonid Brezhnev takes a day off to show his mother his city mansion and his country dacha. That evening at dinner his mother says she is impressed but whispers with concern, “But Lenya, what happens if the Bolsheviks come back?” Or: “tass reports that the latest Five Year Plan will have the Soviet Ministry of Electronics design the world’s largest microchip.”

These jokes — and the fact that the embassy passed them along — reflected an important underlying truth. Americans knew, at least at some gut level, that despite the Soviet Union’s enormous military power, it was internally weak. Its economy was hopelessly inefficient. Its citizens had lost faith in their leaders. Even the political elite was jaded and cynical. Indeed, U.S. grand strategy — containment — was based on these truths. American leaders assumed that, if the United States countered Soviet attempts to expand its influence and control, eventually the fault lines within the Soviet Union would either cause its collapse or morph it into something less threatening.

Compare that to today. Since 9/11, I have never heard these kinds of jokes about al Qaeda, either in government circles or in academia. For that matter, I cannot recall hearing any kind of humor in this vein about China, North Korea, the Putin regime in Russia or the fundamentalist government of Iran. I suspect this is because most experts understand, at least intuitively, that we are dealing with threats today that are fundamentally different from the one we faced in the Cold War.

The Soviet threat was obvious and imminent. It consisted of three well-understood problems: 2.3 million Warsaw Pact troops poised to attack Western Europe; 12,000 nuclear weapons targeted against the United States; and a global campaign of subversion and “wars of national liberation.” The threats that face us today, in contrast, present less potential for Armageddon, but conflict is more likely, and, where the Soviet Union was brittle, they are resilient and seem unlikely to disappear soon.

As a result, we are now witnessing the emergence of a new factor critical to designing a national security strategy: sustainability. America’s goals of ensuring peace, creating wealth, and promoting human rights and rule of law depend on our keeping our predominant position in the world, and we will likely need to do so for a long time. So we must think carefully about how the United States paces itself while also keeping a position of advantage over our competitors.

Threats, challengers, competitors

Sustainability is not about living with “limits to growth” (a buzzword popularized by the Club of Rome in the 1970s) or about avoiding imperial overreach and decline (the concern of historian Paul Kennedy in the 1980s).1 It is also not a codeword for knee-jerk multilateralism under the rationale that today’s problems are too big for the United States to “go it alone.”

To the contrary. Sustainability is about making carefully calculated assessments of how the United States expends its military, economic, and diplomatic resources in such a way as to preserve American predominance for as long as necessary. Our other goals depend on this predominance, and so sustainability is a way to maximize the likelihood we will achieve them.

Sustainability will be a central problem for national security for many years to come. The reason is that, in at least one dimension in which the Soviet Union was fatally weak, our potential adversaries are remarkably strong. Consider:

| Soviet citizens hated their government so much that the regime had to wall them in to keep them from fleeing. |

Morale and motivation. Soviet citizens hated their government so much that the regime had to wall them in to keep them from fleeing. Warsaw Pact “allies” viewed the Soviet Union as an occupying power. Marxist-Leninist ideology lost any sway it ever enjoyed among the masses by the 1970s. The Kremlin leadership consisted of old, pampered, faceless apparatchiks whom Soviet citizens feared, loathed, and laughed at. Meanwhile, the most highly regarded Russian intellectuals, like Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov, were considered enemies of the state.

Compare that to al Qaeda today. Members of al Qaeda are willing to crash aircraft into buildings and explode backpack bombs in subways. One can say these terrorists and their sympathizers are evil, but one cannot say that they are not highly committed. Militant Islamic fundamentalism is, where it exists, a grassroots movement springing from thousands of mosques and madrasas. Meanwhile, Osama bin Laden is a revered figure in much of the Muslim world. Islamicist websites advocating violent jihad enjoy huge audiences on the Internet.

These factors affect every aspect of U.S. strategy. When an adversary has this kind of broad-based support and commitment, our military planners cannot count on a demoralized opponent. Diplomats have a tougher challenge in the war of ideas. Intelligence officers cannot count on defectors or émigrés eager to cooperate with a regime they admire.

Economic efficiency. The Soviet Union failed largely because of the failures of its command economy. By the 1980s, Soviet gross domestic product was flat, and the United States twisted the knife by accelerating the arms race. The Soviets could not compete and exhausted themselves trying.

In contrast, Mao Zedong’s heirs may keep his portrait over Tiananmen Square, but they aren’t foolish enough to follow his economic notions. Thanks to free-market reforms, the Chinese economy expands at near double-digit annual rates. This economic strength translates into steady growth for the Chinese defense budget, which goes to developing new weapons or buying them abroad.

Yet not only are we are unlikely to stress the Chinese economy into oblivion; we don’t want China to implode like the Soviet Union. The social chaos throughout the Pacific Rim would be unfathomable, and the shelves of Wal-Mart would be empty. The Chinese and American economies are thoroughly intertwined. Total trade between the two countries currently totals about $169 billion annually; according to the People’s Daily, U.S. in-place investments in China total more than $48 billion, distributed in 45,000 projects.

U.S. policy assumes that interaction with the West will eventually lead a new generation of Chinese to demand democracy, and a new generation of Chinese leaders will grant it. But this will be a long process — and current Chinese leaders are betting they can balance economic freedoms with political controls indefinitely. Meanwhile, we face a country that is not quite a threat but certainly not an ally.

And the stakes are considerable. A military conquest of Taiwan by China would be the defeat of a democratically elected regime that respects civil liberties by a dictatorship that does not. That could be a hinge-point of history; the record would show that the Chinese won their wager, and the implications for the future of civilization would be profound.

| North Korea’s elites sell weapons, drugs, counterfeit currency, and prostitution for a comfortable living. |

Prudent foreign policies. Ironically, the Soviet Union was the best advertisement for containment a Western leader could want. It openly supported subversion and revolution abroad. It regularly rehearsed military invasions of Western Europe and trucked its missiles through Red Square in parades. These provocations spurred Western democracies to form defensive alliances like nato and made it possible to rally the popular support needed to build up our own military forces.

Kim Jong Il is a wilier foe. North Korea optimizes its policies to retain power and enrich its elites through a combination of threats, retrenchment, and duplicity. For example, though officially listed as a terrorist state, North Korea has not been linked to a violent terrorist strike for more than a decade. Meanwhile, now that it has demonstrated it can build a nuclear weapon, North Korea can deter most military threats. By never completely walking away from the negotiating table, it can extort concessions. By offering minor accommodations, it splits the South Korean public’s resolve.

Talk about a sophisticated opponent: North Korean leaders understand that, as long as they avoid anything too outrageous, they can remain comfortably in Pyongyang. The ruling elite (sort of a cross between a cult group and an organized crime family) sells enough weapons, drugs, counterfeit currency, pirated goods, and prostitution for a comfortable living. The population of North Korea is about 22 million, but the elite numbers no more than a few hundred thousand. As we are discovering, it is hard to design effective, enforceable economic sanctions that can target this small segment.

Similarly, Iran avoids outright confrontation with the United States by denying it seeks nuclear weapons or promotes terrorism even while there is considerable evidence that it does both. Iranian theocrats have also learned how to use their country’s oil wealth — and carefully modulate its support for Islamic nationalists — to win support from countries such as China and Russia.

The threat from these countries is not that they would attack the United States directly (that would be inconsistent with self-preservation). Rather, the main concern is that they might threaten one of our allies (Japan, South Korea, Israel) or that they might export weapons of mass destruction.

More effective internal controls. Dictators today have learned how to practice “smart authoritarianism.” They impose just enough restrictions to cripple their opponents while avoiding widespread dissent.

For example, Russian rulers — unlike their Soviet predecessors — know better than to throw Nobel peace prizewinners into the gulag. Instead, they imprison unpopular oligarchs — who also happen to be the most likely supporters of a political opposition—and quietly coerce or eliminate less affluent and less visible figures. The regime holds regular elections, but cronies control the broadcast networks.

The remarkable thing about Vladimir Putin, Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is that they all stood for election — and won. Putin even captured 71 percent of the popular vote. True, electoral procedures tilted the playing field against their competitors, but that is just evidence of how deft these rulers are in maintaining control — and, even then, one cannot deny that every one of them has substantial popular support.2 The net result is a set of regimes that are not friendly to the United States but which are politically stable and likely to complicate our national security planning for many years to come.

There are other threats and challenges one could mention and others yet to emerge. But the trend is clear. Today we face a smarter, more complex, and more varied set of adversaries. They are more resilient and more adaptable than the Soviet Union was. All of these opponents will be able to use strategy, tactics, and technology to threaten us where we are vulnerable.

Because these threats will likely be with us for a long time, the United States must pace itself. Thus, the question: If we are in for a long race, what is the best strategy for making it to the finish — and winning?

Balancing passivity and activism

It is hardly surprising that American leaders have struggled to understand how to deal with these new threats. They are complex. Yet, in retrospect, U.S. policy during the past 15 years has ranged from being too passive and letting potential threats get out of hand to being too aggressive and stretching our resources too fast, too far, and, thus, too thin.

Consider how the United States responded to al Qaeda and North Korea during the 1990s. Other than a cruise missile strike following the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, we mainly treated al Qaeda as a diplomatic and law enforcement problem. The terrorists grew bolder, and the result was 9/11. By failing to take effective military action against al Qaeda in time, we allowed Osama bin Laden to train thousands of terrorists in his Afghanistan camps and establish his message of hate and violence among young, alienated Muslims worldwide. Now they will present a threat for many years to come.

We made a similar mistake in dealing with the North Korean nuclear program during this period, relying too heavily on diplomacy and acting as though the North Koreans were serious negotiating partners. The 1994 Agreed Framework was supposed to have Pyongyang exchange its plutonium-based nuclear program for foreign aid. Alas, North Korea took the foreign aid and exchanged its plutonium extraction program for one based on uranium enrichment (and, as the October 2006 tests proved, maintained its nuclear weapons program).

| Social Security is the “third rail” of politics — touch it and die. No one says that about defense spending. |

More recent U.S. policy — triggered by 9/11 — has veered to the other extreme, using military force in such proportions against one threat that we are ill-prepared to deal with others. We have had almost the entire deployable force of the U.S. Army in Iraq, en route to Iraq, or returning from action in Iraq. We are bumping up against the limits of our armed forces’ capacity, and, as we will see, the prospects for expanding the force are not good.

U.S. choices in Iraq are being driven by the fact that the clock is ticking on how long we can keep our forces there. Moreover, when U.S. forces were committed to Iraq, they became unavailable for use elsewhere. American forces were a more effective deterrent before March 2004 than they are today precisely because they were a potential force.

During the Cold War, American policy focused on ensuring deterrence, and this was achieved by meeting well-understood requirements for force levels and maintaining alliances. In the future, the sustainability of U.S. strategy and policy will depend less on simply maintaining deterrence and more on meeting two new criteria.

The first is holding the strategic initiative. This term, familiar to the military community, is the ability of a nation to control the course of a military or political situation, or at least shape it more than our opponents can. When a country holds the strategic initiative, it can decide when to engage its adversary, how, on what terms, and at a point in time when it is most effective in deciding events.

The second concept is flexibility and economy of motion. We need to look for the most efficient, effective mix of actions that both attain our national security goals today and leave the United States in a position in which it is best able to achieve its objectives in the future.

The military dimension

In 1996, William Kristol and Robert Kagan criticized the Clinton administration for scrimping on defense. They baldly argued that the world would be better off with the United States as a “benevolent hegemon” and that it needed a military suited to the task. They wrote:

Republicans declared victory last year when they added $7 billion to President Clinton’s defense budget. But the hard truth is that Washington — now spending about $260 billion per year on defense — probably needs to spend about $60–$80 billion more each year in order to preserve America’s role as global hegemon. The United States currently devotes about three percent of its gnp to defense.3

The $320 billion–$340 billion Kristol and Kagan wanted for defense in 1996 would in today’s dollars equal $388 billion–$412 billion. Defense spending in fy 2006 was, in fact, approximately $450 billion, not including supplemental spending specifically for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. So essentially they got their wish and a bit more.4

The United States can afford this level of defense spending. In recent years the share of U.S. gross domestic product devoted to defense (which roughly represents the burden defense imposes on the national economy) has been about 3–4 percent. During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States typically spent 8–11 percent of gdp.

The problem is political reality. Today there are more activities competing for the federal dollar — in particular, entitlements like Social Security and Medicare. These have grown throughout the postwar period, and there is little support to cut them. Every pundit knows Social Security as the “third rail of American politics” — touch it and you die. No one speaks of defense spending like that. For good or ill, supporters of a strong military are just another interest group.

As a result, while total government spending has hovered in the range of 17–20 percent of gdp since the early 1950s, the percentage share of gdp the United States devotes to defense has fallen steadily as the economy has grown and defense spending has remained flat.

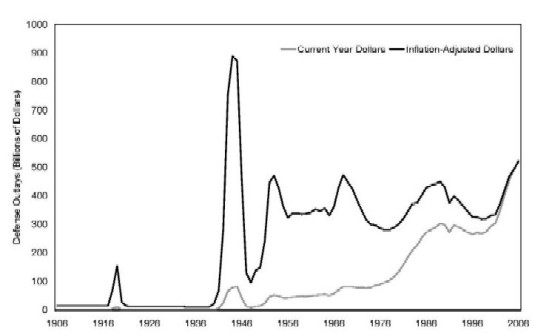

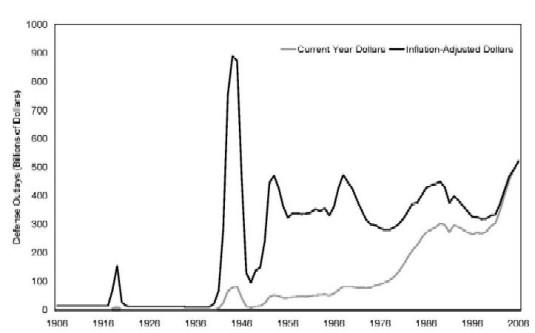

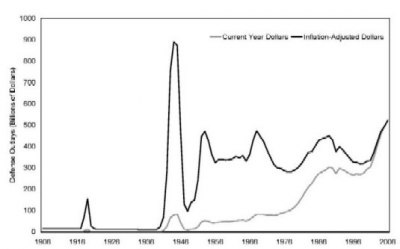

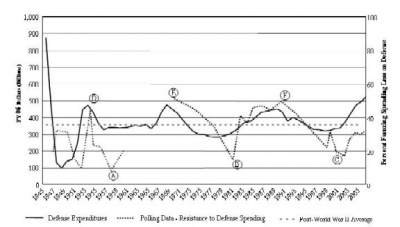

That’s right, flat. The fact that the U.S. defense spending trend line has been flat (adjusted for inflation) usually gets lost in the hurly-burly of annual budget debates, but the two accompanying charts offer some perspective and illustrate how the main constraint on defense spending has been public opinion.

Figure 1 shows U.S. defense spending in inflation-adjusted dollars for the past one hundred years. Note that prior to World War ii, the United States spent little on defense, with the exception of a three-year blip coinciding with World War i. The expenditures of the army and navy together were only about $15 billion per year, which today would put the United States on par with Brazil or India.

Figure 2 focuses on U.S. defense spending since World War ii. Defense spending rose after the Cold War began, reflecting the consensus within the United States to deter the Soviet Union. Yet the most notable thing about the U.S. defense budget since 1953 is that, despite significant swings, annual military spending consistently comes back to an average of about $370 billion. Defense spending rose by a third during the Korean, Vietnam, and Gulf Wars, during the Reagan buildup, and, now, during the recent actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. It fell by about a quarter during the 1970s and 1990s.

Now notice the trend line in public resistance to defense spending, as measured by the Gallup Poll. After several years of declining budgets or after a crisis like the Korean War, the Iran hostage crisis or 9/11, resistance to defense spending reached its trough (Points a, b, and c). But as the military budget peaks, so does public resistance to defense spending (Points d, e, and f).5

The lesson: In the United States there has been a popular consensus supporting large, but not unlimited, defense budgets. One may, like Kristol and Kagan, argue that we should spend more on defense, and one can even make a case that the United States could. But if history is any guide, it is imprudent to assume that it will. There are too many other interests competing for a slice of the budget pie, and enthusiasm for beefing up U.S. forces is a fleeting thing. If history is any guide, five or six years from now the defense budget will be 10–15 percent smaller than currently.

Keep in mind, though, that even though the percentage of gdp that the United States devotes to defense has slipped to about 3.5 percent, it has fallen even further in other countries. And the fact remains that the United States currently spends as much on its military forces as every other country in the world combined.

That is why today only the United States has the capability to deploy significant combat forces far beyond its borders. The only countries that come close are Britain and France, and their deployable combat forces are orders of magnitude smaller than those of the United States. Russia cannot deploy significant forces beyond what some of its officials call in private moments the “near abroad” (meaning now-independent states that used to be part of the Soviet Union). Even with its current buildup, China cannot operate combat forces more than a few hundred miles beyond its coast.

In effect, with the exception of the United States, the world’s armies have, since the Cold War, been designed for territorial defense and contesting disputed contiguous lands or waters. The exceptions, oddly enough, are international terrorist organizations like al Qaeda, which can “project power” by covertly emplacing cells near their targets and linking them to commanders halfway around the world via the commercial global telecommunications network. (This approach, which can also be used by states, is poised to become the mode of “global strike” adversaries are most likely to use against the United States.)

With prudent measures, the United States can keep this advantage for years to come. We may be challenged in one or more regions, but if our forces are flexible in their capabilities and operations, we should be able to reallocate them to deal with a wide range of contingencies. One pitfall to avoid is poor planning that would result in a force that is imbalanced or ill suited for the threats we face. Another is allowing orthodoxy to lock U.S. forces into technologies or doctrines that allow our adversaries to leapfrog us. A third is committing forces to an engagement that is so consuming in time and scope that it creates a long-term drain on our capability.

Besides the cost of defense, there is also the willingness of the public to accept military casualties. This tolerance also defines limits of how assertively and independently the United States can act abroad. As John Mueller recently observed, U.S. public support for wars diminishes in direct proportion to the number of casualties — as casualties mount, support wanes. Except that now the public seems much less tolerant. At the time Mueller wrote, the drop-off in public support for the U.S. military action in Iraq had been significantly steeper than for Vietnam.6

Popular opinion is not opposed in principle to deploying forces abroad. Despite initial concerns, there has been little controversy over maintaining U.S. troops in Germany, South Korea, Bosnia, Kosovo, the Philippines, Kuwait, Qatar, or Honduras. It’s not even combat and risk that are controversial. The issue is casualties; it simply seems that Americans have less tolerance today for losing Americans in combat. (For that matter, even enemy casualties can be highly controversial.) This might not hold if a foreign war were a direct response to an attack on the United States, but otherwise, this reluctance to bear casualties must be considered in planning when and how we can use military forces.

Regardless of what one thinks about the wisdom of intervening in Iraq or the rationale that got us there, the fact is that the United States will not sustain many excursions incurring over $300 billion in costs and several thousand casualties. The lesson is that, while America has a unique capability to fight wars far from home, it is a unique capability within firm boundaries. Straying beyond them will undercut the ability of the United States to use its military power in the future and, thus, its predominance over the long run.

These bounds are important in the context of current U.S. policy. After the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration adopted a military policy that broke with its predecessors. Before, the goal of American military policy was to maintain deterrence across the entire “threat spectrum.” This meant U.S. forces were supposed to be strong enough to deter nuclear attack, conventional war, and low-intensity conflict.

The new policy, in contrast, argues that it is difficult or impossible to deter terrorists and that (as 9/11 demonstrated) the potential costs of waiting to respond until an adversary strikes are unacceptable. Thus, the United States needs the military capability to strike first. The most recent National Security Strategy puts it this way:

We are fighting a new enemy with global reach. The United States can no longer simply rely on deterrence to keep the terrorists at bay or defensive measures to thwart them at the last moment. The fight must be taken to the enemy, to keep them on the run. . . . We must join with others to deny the terrorists what they need to survive: safe haven, financial support, and the support and protection that certain nation-states historically have given them.7

For military planning, however, a “strike first” policy leaves the question of how to strike first. It requires more long-range precision weapons, more combat forces that can operate autonomously and with a small footprint, and more “nonkinetic” weapons targeted on an adversary’s information systems. All of these military capabilities need better intelligence support to find, identify, and target specific people and units and to characterize the environment so that U.S. commanders can develop the most efficient time, place, and means for engaging them.

The diplomatic dimension

Since the end of the Cold War, several authors have written books with a common theme: America as dominant force. Michael Mandelbaum is one of the latest. He argues that the United States provides “public goods” — security and prosperity — that other countries benefit from and cannot provide for themselves.8

Although Mandelbaum is a liberal, his argument is remarkably similar to the case made by Kristol and Kagan — two conservatives — for benevolent hegemony. Joseph Nye, Joshua Muravchik, and others have made arguments in the same vein. Conservatives tend to propose a more in-your-face approach than liberals, but, whatever the route, the arguments usually reach the same destination, concluding that U.S. leadership is good for the world, and ought to be our goal.9

Yet the hegemony advocates have yet to provide much guidance for fitting U.S. military power into foreign policy or, conversely, for how diplomacy should complement U.S. defense policy. The underlying problem is that, while coalitions can help sustain U.S. predominance by conserving resources, managing such alliances is more complex today.

In the Cold War, the United States promoted treaty organizations to contain the Soviet Union (nato, seato, anzus, the U.S.-Japanese mutual defense treaty, and so on). Each formally defined the parties to the treaty. Each contained specific terms under which the parties would assist, cooperate, or consult. The treaties were augmented with sales of military equipment, scheduled combined exercises, exchange of personnel, or common command structure.

Today there is no uber-alliance like nato or even a system of lesser alliances that could deal with all of the threats we face. Even within a single region like the Pacific Rim, there are too many cross-cutting interests and too many interests that change over time. Japan will join us on curbing proliferation in North Korea, and possibly in deterring a Chinese strike on Taiwan; but combating Islamic terrorists in the Philippines? Probably not.

The United States needs the flexibility to assemble whatever coalition it can, both to use military force effectively and to sustain U.S. power. Richard Haass comes closest to a diplomatic approach that supports a grand strategy of sustainability, proposing that the United States play the role of “sheriff,” prepared to round up an ad-hoc posse when there is a need.10

Logically, then, our goal should be to optimize the opportunities and the means for attracting partners for potential military cooperation. To borrow a phrase from domestic politics, this is retail diplomacy, not wholesale diplomacy. Each potential partner must be considered one by one. U.S. officials will have a never-ending task: assessing what it is that other countries want, what they bring to the table for the United States, and how they might fit into U.S. planning. Then we need to develop strategies for taking advantage of these opportunities.

Unlike the Cold War, today the United States will usually need an “à la carte” approach in our politico-military diplomacy. Parsing issues will be the order of the day and business as usual. For example, from the perspective of the United States, France has been awful on Iraq. But the French are among the best supporters of U.S. policy on counterterrorism. Same with Russia. Take what you can get.

So, one might ask, what happens to American principles in this approach? This is a classic problem of realism versus idealism. There is no perfect solution — all policymaking, after all, is a process of reconciling competing priorities. But a good first step would be to distinguish more clearly between the channels and institutions we employ to pursue immediate, pragmatic goals of military strategy from those we use to institutionalize our deeply held, long-term goals of promoting democracy and freedom.

Currently, we often have this relationship almost exactly reversed. The United States has frequently gone to the United Nations to authorize the use of force or to condemn a nation for some transgression, even though most of the delegates who vote on these measures represent unelected regimes where the rule of law is, let us say, capricious. On the other hand, it has recently turned to nato, an alliance of democracies, to attain support for — but not necessarily to legitimize — U.S.-led action in the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Ideally, we would recognize the United Nations for what it really is: an international forum with no particular moral standing because any government can join. The un is often a useful meeting place in which countries can negotiate agreements when it serves their interests and a bilateral treaty is impractical. Attributing any authority beyond that, however, misconstrues its legitimacy and also impedes U.S. freedom of action. Indeed, the very structure of the un and its procedures are designed to prevent any country from pursuing a policy aimed at achieving predominance.

In short, we need lane discipline that avoids mingling our strategic interests with our principled ones. U.S. support of democracy, freedom, and rule of law would be better served by organizations that are explicitly designed to promote those values. A “congress of democracies” could promote the development of democracy. If asked, it could pass resolutions endorsing a military action. The United States would have to lobby and compromise to win such approval, but at least it would be dealing with its peers on issues of principle.

Finally, U.S. foreign policy should avoid increasing the potential cost of these ad hoc alliances. According to an often-cited Pew Global Attitudes Survey published in June 2005, the United States is “broadly disliked in most countries surveyed.” Fewer than half the respondents surveyed in such traditional allies as the Netherlands, France, Germany, and Spain currently have a favorable opinion of the United States. In key Muslim countries like Turkey and Pakistan, only 23 percent of the public has a favorable view of the United States. Even in Lebanon, where the United States was critical to the success of the Cedar Revolution, support runs only at 42 percent.11

Foreign policy is no popularity contest, but if the United States succeeds in promoting democracy abroad, foreign support for U.S. military action will inevitably depend more than ever on foreign public opinion. U.S. leaders must avoid drawing lines in the sand needlessly; one might find a would-be ally is on the wrong side. Probably the first rule of being a successful hegemon is to avoid telling the world that hegemony is your goal.

General rules

In sum, a strategy recognizing the need for sustainability would be developed consistent with these principles:

Know your long-term resources; aim for a concerted, sustained effort that is affordable and commands broad public support.

Be proactive in dealing with threats, even if this requires unilateral military measures; modest amounts of force now may avert the need for larger, unaffordable amounts of force later.

Be pragmatic in dealing with allies and potential coalition partners; don’t create unnecessary animosity, costs, or friction.

Yet be clear about the enduring values and goals the United States seeks. Officials need to be frank and sincere, not coy and calculating in public statements. We can trim our values from time to time when the situation demands, but officials need to be honest about it if they hope to keep public support.

Work as hard as necessary for a bipartisan consensus on long-term goals; the United States cannot maintain a predominance strategy based on 51 percent of the public as measured every four years on election day. Containment worked because it enjoyed broad support for many years.

Military power will be important, but soft power — American culture and international commerce — will, over time, have a greater effect in defeating or transforming our adversaries.

Conventional military power can change facts on the ground dramatically and quickly. But it is too expensive to be used for long periods, and is weak compared to the tidal effects of demographic and economic trends that shape the world over the long haul. Like an expert mariner, the United States needs to ride these tides — which do run in our favor — so that we can reach our destination efficiently and assuredly.

The United States can retain its predominant position in world affairs, and it should be national policy to do so. Our broad goals of promoting democracy, freedom, and peace all depend on it. So do our more immediate goals of integrating emerging countries such as China into the world community and defusing religious fundamentalism as a vehicle for terror. However, maintaining our predominance requires a deft touch. Achieving this level of sophistication in U.S. strategy and policy may be the greatest challenge of all.

1 See Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens iii, The Limits to Growth (University Books, 1972), and Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (Vintage Books, 1989).

2 See Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and George Downs, “The Rise of Sustainable Autocracy,” Foreign Affairs 84:5 (September/October 2005).

3 William Kristol and Robert Kagan, “Toward a Neo-Reaganite Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs 75:4 (July/August 1996).

4 The Congressional Budget Office estimated that defense outlays in fy 2006 would total $522 billion and that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, funded through supplemental spending bills, were costing about $7 billion per month. See The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update (Congressional Budget Office, August 2006).

5 No good polling data are available from 1961 through 1969, but the high level of resistance to military spending measured by Gallup in 1969 suggests how it rose during the Vietnam buildup. Notice the spike in resistance to defense spending in May 1999; Gallup happened to take its survey at the height of nato air strikes against Serbia during Operation Allied Force, including the day a U.S. aircraft accidentally bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade.

6 John Mueller, “The Iraq Syndrome,” Foreign Affairs 84:6 (November/December 2005). .

7 National Security Strategy of the United States (The White House, March 2006). .

8 Michael Mandelbaum, The Case for Goliath: How America Acts as the World’s Government in the Twenty-First Century (PublicAffairs, 2006).

9 See Joseph S. Nye, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (Basic Books, 1990), and Joshua Muravchik, The Imperative of American Leadership: A Challenge to Neo-Isolationism (aei Press, 1996).

10 Richard N. Haass, The Reluctant Sheriff: The United States After the Cold War (Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1997); see also his The Opportunity: America’s Moment to Alter History’s Course (Public Affairs Books, 2005).

11 See Andrew Kohut et al., “American Character Gets Mixed Reviews: U.S. Image Up Slightly, But Still Negative,” Report of the Pew Global Attitudes Project (Pew Research Center, 2005).