- Values & Social Policy

- Race & Gender

On June 23, 1972, Congress passed Title IX of the Civil Rights Act, which over the past fifty years has transformed the world of intercollegiate sports. Its basic command reads:

- Prohibition against discrimination; No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Title IX has grown mightily since it was enacted. It is backed by detailed federal regulations, coupled with an exhaustive manual from the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, both intended to prevent any backsliding by colleges and universities that receive any federal aid for any part of their operations. Except for a handful of holdouts, every major educational institution takes federal funds, so Title IX has had an enormous impact on college sports.

And yet Lindsay Crouse, a well-known retired actress, has just written a lengthy cri de coeur essay in the New York Times: “We Can Do Better Than Title IX.” Her impassioned thesis comes in two parts. The first praises Title IX for its success. The second denounces American culture because it has not followed through on Title IX’s promise of letting American girls “enjoy the same opportunities in school sports as boys.”

Both points are contestable.

First, one must take a closer look at both the gains and losses from Title IX. On the positive side, female participation in intercollegiate sports increased greatly from about 32,000 in 1972 to about 190,000 in 2012. It would be, however, a mistake to attribute that entire increase in women’s participation to Title IX. In the five years before the adoption of Title IX, participation in women’s intercollegiate sports nearly doubled from just over 15,000 per year to just under 30,000; male participation during that same time period increased by a little over 10 percent, from just under 152,000 to just over 170,000. Surely, those trends would have continued without Title IX, for it is wholly implausible to assume that over the past fifty years nothing else would have changed, when the same social forces that led to the adoption of Title IX were at work everywhere in society.

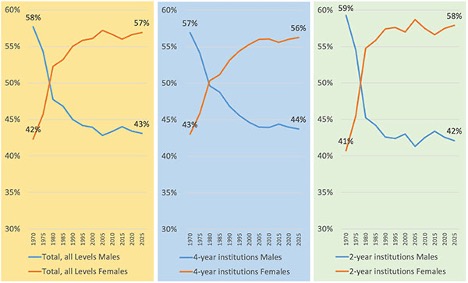

The percentage of women enrolled in college (see chart) rose from about 42 percent of college populations in 1970 to about 57 percent today, with most of that increase coming before the year 2000.

With no change whatsoever in policy, there would have been about a one-third increase in female athletes and about a one-quarter decrease in male athletes, shrinking the gap. Indeed, in the absence of Title IX, female athletes would have certainly made their demands known to colleges, while the sharp increase in female faculty and administrators would have driven further changes.

Title IX of course did not affect the athletic opportunities only for college women. It did the same for men, only in the opposite direction. Their prospects were diminished, as a prospective male athlete had a lower chance of getting a coveted intercollegiate position. The 1979 EEOC guidelines instituted a novel legal regime to respond to the general trend of men participating in intercollegiate sports (including sports like football and wrestling, where there is little female interest) at a far higher rate than women. It then added a gloss that required every college to take continuous steps to correct that gender imbalance, since virtually none had proportionate levels of participation. The upshot was that the hard-pressed colleges offered female athletes large scholarships while male athletes beg to pay their own way, leaving unhappiness among both men and women. The most conspicuous consequence was that male varsity teams were deeply cut. Accuracy in Academia points out that “NCAA statistics show [as of 2005] that men’s cross country leads the list of most dropped programs in the last 15 years at 183. Indoor track (180), golf (178), tennis (171), rowing (132), outdoor track (126), swimming (125), and wrestling (121) are other men’s programs that have been cut mainly because of current Title IX enforcement.”

Schools had to make those massive cuts because there was no way to boost female participation in sports up to the levels of men without diminishing the commitment to men’s sports. So long as college football constitutes a huge portion of the male base, minor men’s sports will suffer even if there is greater demand for them than other women’s sports.

Remove the constant pressure of Title IX, and it seems likely that dramatic growth in women’s sports would continue, perhaps at a more modest rate, but it would not come at the expense of men’s sports. But Crouse, like other defenders of Title IX, never asks this question: how many male athletes should be denied the opportunity to participate for each additional female athlete? A market solution would give colleges greater control over their budgets, and over their athletic mix. In all likelihood, it would increase the total number of students, male and female, in intercollegiate sports.

For Crouse, however, the real breakdown comes after college, when Title IX is no longer in play. She condemns the dismal record whereby male-dominated sports, with a few exceptions, receive far larger audiences and revenues than female sports, due in part to (although she does not quite say it) the preferences of female sports fans. In this unregulated market, people like to watch men’s sports because, as she notes, men are “bigger, faster, and stronger.” Professional athletes are of course drawn from the top ranks of both sexes. In only a few sports—equestrianism, for example—do men and women compete regularly on equal terms.

Crouse recognizes that no law can change the relative strength of men and women, making it pointless to have male-female teams in sports like golf or track and field, let alone football and basketball, even though specialized events like mixed doubles have a long history in tennis. Men’s sports generally command larger audience because forces of supply and demand, stifled by Title IX parity requirements, reassert themselves. And men constitute by far the largest fraction of the audience. Only when nonmarket forces are at work will equal pay for equal play gain traction. Indeed, the superior performance and higher ratings of the US female teams in international but not league competition might well command a pay premium in the first market but not the second.

Faced with these stubborn facts, Crouse concludes that “we must dismantle the systems that favor male-dominated athletes.” But who are “we” and how should those people proceed? In the end, Crouse wants us (i.e., someone) to reshape cultural preferences so that we can “cultivate” tastes for the women’s sports that capitalize on women’s superior flexibility and endurance. Nonetheless, these underlying dynamics tell the tell the tale: 39 percent of women never watch sports, as opposed to only 17 percent of men. But at the opposite extreme, 19 percent of men watch sports daily, as opposed to only 2 percent of women. Thus, markets already do just that sorting function. Female athletes attract large audiences in sports like gymnastics and figure skating, not to mention in artistic venues such as ballet, precisely because they can do things that men cannot achieve. Case in point: Gertrude Ederle, who in 1926 broke the previous world’s record by two hours and became the first woman to swim the English Channel.

To Crouse, these efforts have not sufficed. “We” must go even further, inevitably through a propaganda campaign that seeks to indoctrinate people, including male sport junkies, into liking women’s sports.

Yet market forces offer a better way. Women’s sports should hire managers and advertisers to “reimagine” their sports to make them more attractive to ever-larger segments of the economy. But by the same token, in a market economy, they have to compete with men’s teams and sports that are determined to keep or increase their market share by using the same strategies. The good news is that this competition is likely to expand the total pie for all sports, leaving their relative shares to market successes, and catering to the viewing and rooting interests of more and more people.

Crouse, however, ominously calls for a “New Deal”—cross reference intended—whereby public money is used to expand female opportunities to obtain leadership positions in coaching, managing, and media relations. These subsidies bode distorted market outcomes in a way reminiscent of Title IX. But ironically, as Crouse notes, as women’s sports grow, market competition for these leadership positions becomes stronger. Even now, women have been pushed aside for coaching positions in women’s college basketball. Ninety percent of coaches for women’s teams before Title IX were women, while today, as the game has grown in stature and wealth, only 43 percent of the coaches of women’s team are female.

Crouse is discomfited by this unanticipated shift in fortune, but it is what anyone should expect. When the dollars get large, cross-subsidies are bled out of the system.

Crouse would like to change that familiar pattern by starting a pipeline of new recruits that would build flexibility into the system and make allowances for pregnancy. But if that approach hasn’t worked to date, it won’t work in the future, unless we ban all men and many women from competing for these plum positions.

Crouse ends on a sour note, insisting that the world of equal opportunities has not come to women in sports. But rather than seeking to reshape preferences and commandeer the job-creation project, Crouse might want to consider the unthinkable: to have women use their talents in areas where they have comparative advantages, either within or outside of athletics. It is not my place, nor Crouse’s, to tell them what these places are in business, the professions, or the arts. As responsible and educated citizens, grown women, like grown men, must figure that out themselves. And they will do far better if sensible policy makers disregard Crouse’s dangerous advice.