- Economics

- Budget & Spending

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- History

- Contemporary

- World

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

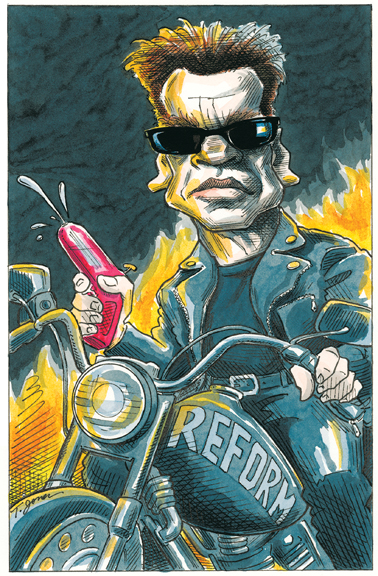

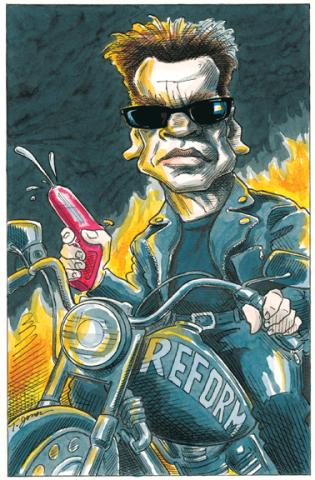

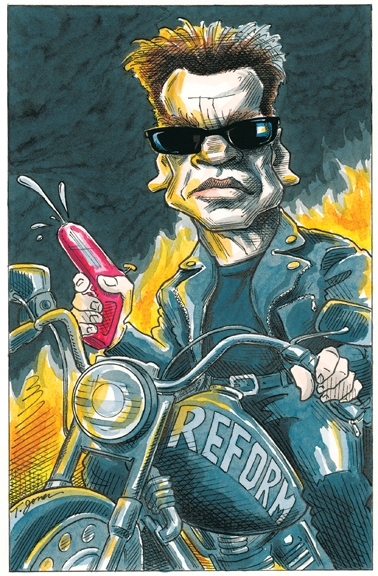

As California stumbled forward this past summer under its long-delayed, draconian budget process, I couldn’t help but wonder what might have been had Arnold Schwarzenegger pushed for more meaningful fiscal and political reform immediately on taking office in 2003.

The Arnold of the Golden State’s recall election was the Barack Obama of the 2008 presidential election. He was a man of wealth and privilege, restyled as a populist outsider and overhyped by a fawning media, who came into office with a window of opportunity to achieve most anything his heart desired. For Schwarzenegger, that window remained open for about a year.

Sacramento Democrats recognized that taking on the celebrity governor was a fight they would lose, but Schwarzenegger failed to seize the opportunity—at least, not beyond the modest step of temporarily mending California’s workers’ compensation system. Schwarzenegger needed to make entrenched lawmakers an offer: either work with me on budget and government reform so everyone can have a nice, bipartisan bill signing or expect a knockout fight at the polls over a set of ballot initiatives.

Had he done so, he might have gotten some of the good ideas that the state needs—such as setting up a serious rainy-day fund and creating an honest spending cap—enacted into law.

Would the Democrats who control California’s legislature have rolled over that easily? We’ll never know. But the threat of taking the issue to the voters is how the governor got workers’ comp reform through the legislature within six months of taking office.

Schwarzenegger did offer a plan to revamp state government during his honeymoon phase in 2004. But his approach—the “California Performance Review,” or CPR—was a metaphor for his political failure. It involved a 275-member task force that produced a 2,500-page proposal. That report, which offered upward of $32 billion in savings, never caught anyone’s fancy. It was too complicated for voters to rally behind and legislators didn’t want it enacted. It was dead on arrival.

Instead of reform, the man who promised to “blow up the boxes” of government six years ago embarked on a crusade to save the planet—a “greener” approach to governing that helped pave the wave for an easy reelection win in 2006. If Schwarzenegger’s political obituary were written today, its narrative would turn on environmental issues such as solar roof panels, hydrogen cars, and emissions curbs. Missing would be the issues that got him elected in the first place: tax cuts, fiscal discipline, and restoring dignity to Sacramento. The governor didn’t blow up any boxes; he just put “recycle” labels on them.

SEEKING A POLITICAL CORE

This is not to berate Schwarzenegger for evolving as a public servant. But the nagging question about the governor involves his core convictions and stick-to-itiveness. Last year was supposed to be, according to a declaration from the governor, “the year of education.” Before that, we were in “the year of health reform.” In 2005, his theme was “the year of reform.” None of these slogans translated into tangible changes. In fact, 2005 culminated in a special election in which all four of the governor’s proposals (curbing teacher tenure, reining in union dues, capping spending, and redrawing political districts) failed spectacularly. They failed because of a $100 million war chest compiled by Democratic-friendly unions and months of guerrilla campaign tactics at Schwarzenegger’s expense—the sort of thing that would have been politically difficult for entrenched special interests in the honeymoon months of early 2004.

The take-home message of the Age of Arnold is this: catchy sloganeering has given the state’s most pressing problems the look and feel of coming attractions. (Imagine the movie trailer for Health Reform 2007: This Time, It’s Personal.) And the constant showdowns at the ballot box (seven special and general elections since 2002) have voters asking repeatedly: what exactly do lawmakers do in Sacramento?

In theory, this approach could have played to Schwarzenegger’s strengths as a cinematic action hero and a skilled marketer. But the public isn’t buying what he’s selling. Californians apparently are in no mood to follow a governor and legislature whose combined approval rating is below 50 percent (surveys taken after Sacramento ended its budget stalemate showed Schwarzenegger with an approval rating well below 30 percent).

The low point may be last May’s defeat of a package of Schwarzeneggerbacked initiatives that were supposed to solve the chronic budget problem. That no-confidence vote could offer a lesson on leadership and principles for Schwarzenegger: politicians who play to the middle by championing triangulation or “postpartisan” tactics have trouble finding core constituencies. And it was core voters who turned out on May 19 to shoot down the governor’s initiatives: liberals came out because they were worried about spending cuts, and conservatives turned out because they were enraged by the thought of higher taxes. The moral of the story is that core voters look for core beliefs.

Where is Schwarzenegger’s core? Is he the free market, antitax candidate of the recall? The right-of-center union buster of the 2005 special election? The humbled, bipartisan eco-warrior of the 2006 re-election campaign? The tax-and-spend-and-cut Sacramento insider?

AN ODDLY FAMILIAR SCRIPT

Rather than spend Election Day in California, Schwarzenegger attended a public event at the White House. At one time, any visit by him to the nation’s capital would have sparked a flurry of stories about the need for Republicans to adopt his winning ways and amend the U.S. Constitution to allow him to seek the presidency. Today, Republicans running for governor in California go out of their way to point out how they differ from him.

Maybe Arnold Schwarzenegger will be able to mount another political comeback. But that will be difficult, as Sacramento already is consumed with talk of another mounting deficit and the need for even more draconian cuts.

Ironically, it’s the state’s fiscal crisis that, in a sense, turned back the clock on Schwarzenegger’s political persona—back to his right-of-center recall style and agenda. Californians saw not the glad-handing centrist willing to cut deals with the left on all forms of social policy but the emergence of a Republican governor who not only made serious spending cuts but also resisted calls to raise taxes.

As his final year in office approaches, such is the new reality for Arnold Schwarzenegger. A legacy once dominated by feel-good bipartisanship is slowly giving way to a time of limited options and tougher brand of leadership— resulting in decisions that, although not politically popular, are in California’s best interest.

For Schwarzenegger, it’s not the same happy ending one finds in the movies. But in politics, life doesn’t always imitate art.