- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

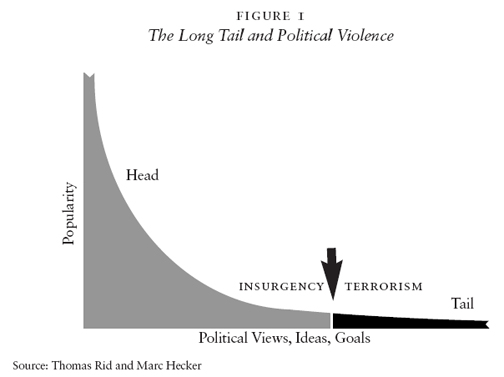

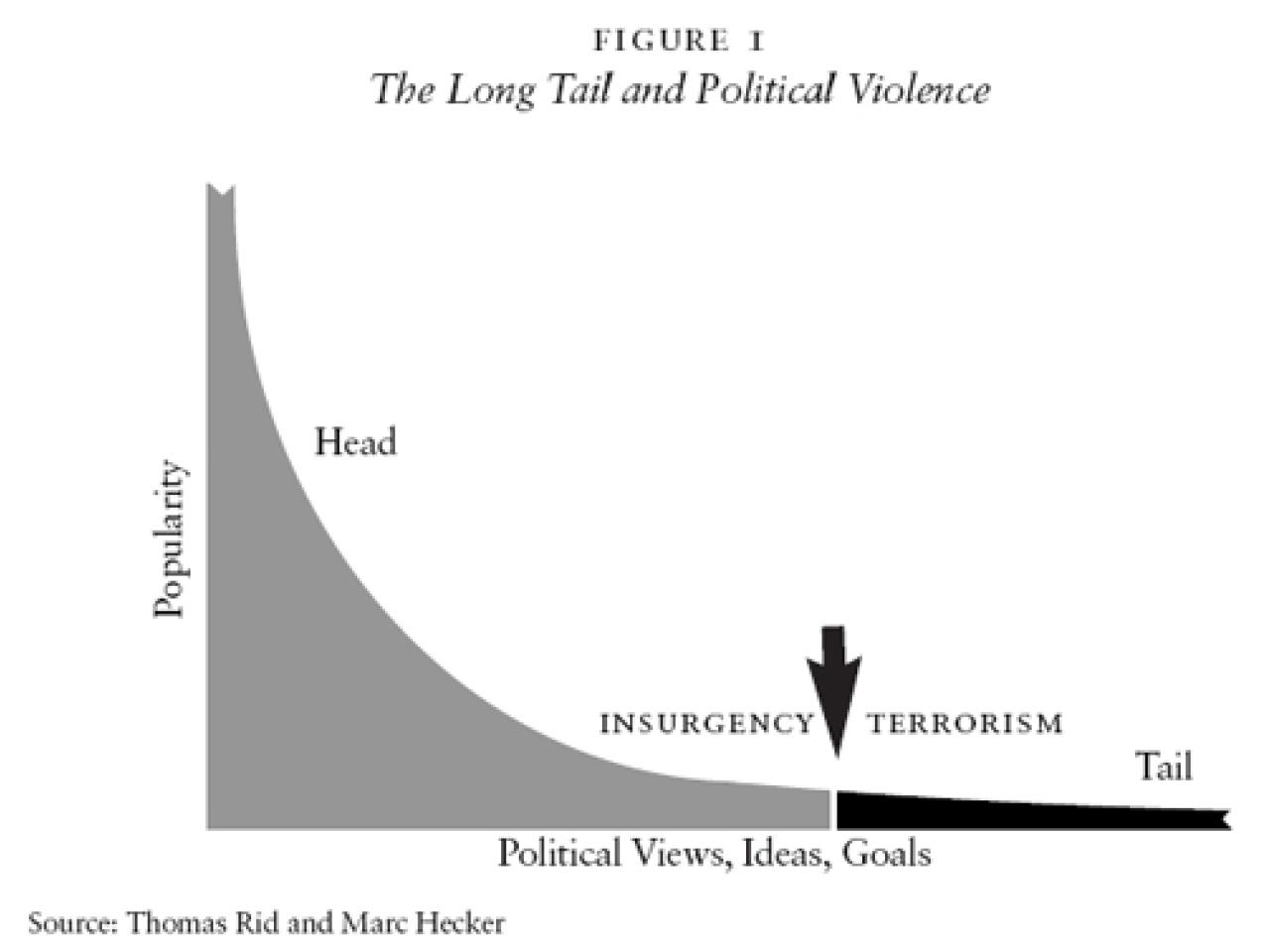

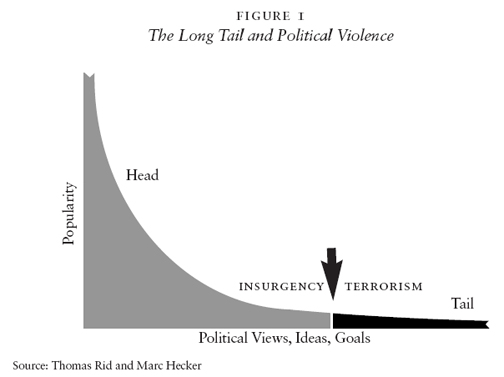

The afghan-pakistan border region is widely identified as a haven for jihadi extremists. But the joint between local insurgencies and global terrorism has been dislocated. A combination of new technologies and new ideologies has changed the role of popular support: In local insurgencies the population may still be the “terrain” on which resistance is thriving — and counterinsurgency, by creating security for the people, may still succeed locally. But Islamic violent extremism in its global and ambitious form is attractive only for groups at the outer edge, the flat end of a popular support curve. Jihad failed to muster mass support, but it is stable at the margin of society. Neither the West nor its enemies can win — or lose — a war on terror.

Western anti-terror policy rests on the assumption that the threat of violent extremism has to be treated at the root — in Afghanistan. A stable Afghan-Pakistan border region, the theory goes, would stop exporting terrorism to the rest of the world. “Our strategy is this: We will fight them over there so we do not have to face them in the United States of America,” in former President George W. Bush’s words. President Barack Obama, it seems, has taken over a strategic mainstay from his predecessor: “I want the American people to understand that we have a clear and focused goal: To disrupt, dismantle, and defeat al Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan,” the president said on March 27, upon announcing his new strategy. This approach is indeed shared by many allies in Europe; confronting the jihadi menace in distant theaters, they agree, will make the homeland safer. In the argument’s strong version, comprehensive counterinsurgency is the right means to that goal; a weaker version is limited to going after the hardened jihadis.

This approach to countering terrorism, in both versions, is predicated on a more general assumption: that global terrorism and local insurgency are flipsides of the same coin. Insurgencies thrive on chaos and failed governance, environments from which they can, through terror, extract popular support and ultimately political success. The local population, therefore, is the critical “human terrain” of modern wars. Creating a safe environment for the population in one area, and making that area fit for basic governance and commerce, would win over popular support and choke the insurgency. Spreading these pacified areas like “oil slicks” would thus eliminate terrorist “safe havens.” Terrorism and insurgency, in short, are seen as tightly linked. Modern land forces, in General Rupert Smith’s commonly used phrase, win “among the people.” But how valid is this old assumption in the ninth year of Operation Enduring Freedom?

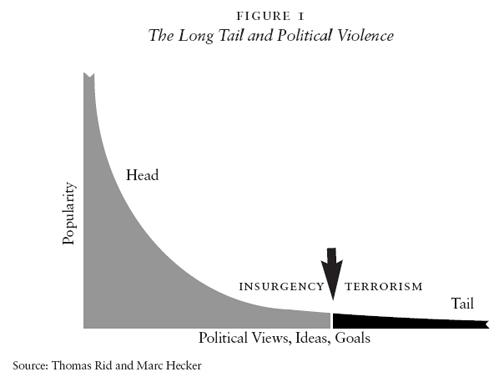

The linkage between terrorism and insurgency has been altered in the early 21st century. Instead of seeing high-volume popular support in an insurgency as the “soil” on which resistance and terrorism are flourishing — and counterinsurgency as a competition for that support — an additional paradigm is needed: the “tail.” Islamic violent extremism is attractive only for a fringe group, the low-volume end of a popular support curve. Individuals and groups at the extreme margin hold views and embrace methods that antagonize mainstream society, in Lashkar Gah as well as in London. Yet, because of increased efficiencies in the distribution, manufacturing, and marketing of Salafist ideas and tactics, the demand and support for — and thus the feasibility of — violent extremism has become more independent of mainstream popular backing. The terrain analogy may retain limited relevance to grasp the role of the population in local insurgencies with a political and territorial agenda, and these local insurgencies might continue to be of interest to some militants with a global agenda. But the support base for global terrorism fueled by ideology and uprooted activists remains at the tail, not at the head — it is therefore immune to many of the methods that are employed to combat insurgency. As a result, oft-used historical analogies and much-touted “lessons” from previous counterinsurgencies, including Iraq, stand on shaky ground.

Terrorism or insurgency?

At least two different academic disciplines and professional specializations draw a line between terrorism and insurgency: the study of terrorism and political violence on the one hand and the study of modern warfare on the other. In national security administrations, that differentiation corresponds to counterterrorism agencies on the one side, predominantly domestic intelligence and law enforcement, and expeditionary military counterinsurgency forces on the other side. The dividing line, however, has begun to erode in the first decade of the 21st century, both in academia and in policy. What used to be called the “global war on terror” has disintegrated into various “counterinsurgencies” on its regional battlefields. And some have proposed to use that terminology on a global scale as well.1 Yet there are important differences.

Terrorism is an initial tactic, not a long-term political strategy. It aims to inculcate fear and to intimidate direct opponents as well as third persons. The perpetrators of terrorist acts may have a political, ideological, or religious motivation. Terrorism as a tactic can be used to undermine the legitimacy of established authority and governments. But it does not create legitimacy for the attacker, and terrorism cannot be used to establish authority or governmental institutions. If a militant group employs terrorism as a tactic without a constructive political program over an extended period of time, it tends to push its perpetrators to the extreme and erode its more moderate supporters’ faith in the cause.

Terrorism may not have a territorial agenda. Al Qaeda, the movement that embodies global jihad more than any other, has — contrary to its name — carious local support bases. The goal that comes closest to a “political” ambition is the creation of a caliphate, either globally or regionally, an objective only very few individuals will consider realistically achievable. Al Qaeda’s rotting roots are exposed by the way the movement treats young converts. It is the only militant group that gives converts responsibilities “beyond all comparison with any other Islamic organization,” pointed out Olivier Roy, one of France’s leading experts on radical Islam. He put the proportion of converts in al Qaeda between 10 and 25 percent. Many of jihad’s diverse recruits might have joined far-left (or far-right) groups in the past. A formerly Arab group drew in activists from a diverse set of Muslim countries and even from non-Arab Muslims from various diaspora communities. Roy sees al Qaeda as a “de-culturalized” movement that has lost touch with local communities. The downfall of al Qaeda in Iraq during the Anbar Awakening can be seen as an expression of this problem, although the group’s Iraqi branch actually had roots in the local community.

Salafism’s global fringe has no defining and common social profile. Instead recruits join the jihad for a variety of reasons and come from a variety of backgrounds: some want to rebel against the establishment; some want to leave their family or country behind; some find a fraternity free of racism in Islamist circles; some have remaining anti-imperialist resentments and embrace the fight against former colonial powers; some have a career in petty crime and a low threshold to use violence. Yet all these motivations have two things in common: They apply to those from the outer edge of their society of origin, and their motivations have no appeal for the mainstream.

The basic organizational units of global jihad are small, not large. It is not a territorial constituent with a high volume of support that forms the basis of global jihad, not an ethnic group, not a religious denomination, not the population of a particular patch of land, and not a nation or the umma on its way to liberation — its core building blocks are small groups of like-minded but diverse individuals who become radicalized among peers, in universities, prisons, mosques, sports clubs, and neighborhoods. Once radicalized and excluded from the mainstream, the bonds to peers become more intense as in-group pressure mounts, and they may be further forged on trips abroad to study Arabic, learn the “true” Islam, or undergo military training in a camp. The constituents of global jihad are cells, “bunches of friends,” or “brothers,” in the language of jihadis, not budding political parties. The attack statistics bear out this trend. Terrorism researcher Marc Sageman recently pointed out that more than three-quarters of all jihadi terrorist plots in the West in the past five years came from autonomous homegrown groups without connection to al Qaeda’s core group.

Insurgency, in sharp contrast, always has a political objective and a strategic aim: the overthrow of established authority or the breakaway from constituted government. The basic organizational units of insurrections are large ethnic or national groups, not scattered peer groups; these have territorial agendas that serve local constituencies, not a global one. All this is illustrated by what is at the same time the hallmark of a successful insurgency: a strong cause. The cause is a necessary requirement that distinguishes a rebellion and political violence from being merely a plot or organized crime. The cause is the answer to the question of how to mobilize popular support both active and passive. Causes come in many forms: gaining independence from foreign oppression, fighting for freedom against an authoritarian government, or ending discrimination against one ethnic or religious group by others, to give just a few examples. A collective feeling of grievance is at the bottom of every protest movement. The cause is an insurgent movement’s instrument for tapping into the general population as a recruitment pool. A successful cause has to meet several criteria. First, it needs to maximize the number of supporters while minimizing the number of opponents in the population. Second, a cause has to be strong. It needs to self-motivate fighters, as they cannot be recruited, conscripted, paid, or simply called to duty for king or country. Third, the cause must be taboo for the counterinsurgent. If the government can espouse the insurgency’s cause without losing its authority and cutting back too much in its interests, it is in a position to take away the insurgency’s most valuable asset. Finally, a cause has to be of long duration. Economic disparities between classes, for instance, are only a source of revolutionary energy as long as crass inequalities in income distribution continue feeding the grievances of the deprived. If political and economic change affects the cause, it may cease to be one.

The cause is an insurgency’s most valuable asset, particularly in the early phases of resistance and subversion. During its embryonic phase any insurgency, wrote David Galula in his 1964 classic Counterinsurgency Warfare, is “as vulnerable as a new-born baby.” It is in this early phase that an insurrection may apply terrorist tactics, inadvertently overplaying its hand. A budding insurgency is likely to face conventionally superior government forces. In such a situation, attacking the security forces is more costly and dangerous than attacking soft targets, such as civilians and unprotected installations. Terrorism then serves a useful purpose: It undermines the government’s legitimacy and the authority of the counterinsurgent forces. Each explosion and each kidnapping make the argument that the security forces are weak, that their power is limited, and that their patience is eroding. On the other hand, civilian casualties make it more difficult for insurgents to argue a good cause. Each civilian casualty makes the argument to neutral observers that the insurgents disrespect human life, that they are weak, that they are incapable of hitting real military targets, and that they are not worthy of support. A budding insurgency therefore walks a fine line between delegitimizing the government and delegitimizing itself — only a robust cause can help it survive this initial phase.

In sum, a successful insurgency aims for the mainstream and aspires to a large following and high volumes of popular support; it is always political; it always has a local territorial agenda, and one overarching strong cause, even if many “accidental guerillas” may fight for opportunistic reasons.2 The opposite is true for jihadi terrorism: It tends to the extreme; it musters only a small following and a low volume of support; it is more ideological than political; it has assumed a global dimension, and combines many incompatible weak causes — Salafists take action for ideological reasons, and there are few “accidental terrorists.”

The soil

The so-called human terrain dominates strategic thinking today. “While we recognize our enduring requirement to fight and win,” wrote General William Wallace in the foreword to the U.S. Army’s capstone doctrine, the Operations field manual updated in 2008, “we also recognize that people are frequently part of the terrain and their support is a principal determinant of success in future conflicts.” Contemporary American strategic thought understands irregular wars as a competition for the trust and the support of the local civilian population. During an insurgency the population essentially falls into three groups: a small and disenfranchised fringe group initially supports insurgents; those who want to see the counterinsurgent and the government succeed; and a neutral, uncommitted, and apolitical group. Both the insurgent and the counterinsurgent compete for this last group’s support, for the group’s acceptance of the counterinsurgency’s authority and legitimacy.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the French grappled with a similar problem. Then the analogy of the human terrain was unearthed. Joseph-Simon Galliéni and Hubert Lyautey, building on decades of experience in countering insurgencies in places as far flung as Algeria, Western Sudan, Tonkin, Madagascar, and Morocco, pioneered the oil slick method in France’s Asian and African colonies. There they laid the conceptual foundation for today’s counterinsurgency thinking. “The pirate,” as insurgents were often called at the time, “is a wild plant that grows only in certain terrains,” Lyautey analyzed. The terrain stood for the population, which the insurgents need as victims and supporters. “And the surest method [to success] is to render that terrain refractory,” Lyautey advised. Removing an insurgency’s foundation by securing, organizing, and administering the population — “isolating the conquered soil” — meant to “turn the population into our foremost helper,” he wrote elsewhere. Galliéni, one of France’s most influential thinkers of counterinsurgency and mentor of Lyautey, wrote that “the most fertile method is that of the oil slick, which consists of progressively gaining territory in the front only after organizing and administering it in the rear.”3 And, referring to the opportunistic “pirates,” the general added: Yesterday’s insurgents will help us against tomorrow’s insurgents.

As the U.S. Army and Marine Corps were facing a predominantly local insurgency in Iraq, it turned to the classic theorists of local counterinsurgency to tackle the problem. “Of the many books that were influential in the writing of Field Manual 3-24,” the foreword to the manual’s commercial edition explains, “perhaps none was as important as David Galula’s Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice.” One commentator even called the lieutenant colonel who in the late 1950s served in a small district in Algeria, Aissa Mimoun, the “Clausewitz of counterinsurgency.” Galula’s small book, republished just in time, made many of the old French ideas on counterinsurgency available to U.S. land forces. The field manual repeatedly quotes the author to highlight the unity of political and military action and the need to secure the population: “Essential though it is, the military action is secondary to the political one, its primary purpose being to afford the political power enough freedom to work safely with the population.” In his other book Galula almost quoted the old masters literally — albeit less eloquently: “once the selected area is pacified, it will be possible to withdraw from it an important share of our means and to assign them to neighboring areas, thus spreading like an oil slick on the water.”

The French counterinsurgents used this image long before Mao used a similar but much more widely quoted analogy, that of the insurgent swimming like fish in the water. Mao wrote about the “relationship that should exist between the people and the troops,” referring to his irregular units as troops. Then the chairman introduced his famous analogy: “The former may be likened to water and the latter to the fish who inhabit it.” Both Galula and Mao critically shaped how modern armed forces see the role of the population in counterinsurgency — and by extension in counterterrorism. Indeed the classic approach of creating population security, condensed in Lyautey’s soil image, was still a good fit for countering Iraq’s local insurgencies, and it might be of some use against insurgencies in Afghanistan’s provinces and districts. The soil is, however, a poor and outdated guide to countering global terrorism.

The tail

Globalization, driven by a revolution in communication technology, has changed terrorism more than it has changed insurgency. The conditions and the environment of terrorist violence are greatly affected by the 21st century’s information environment, a subject of enormous complexity that fills many books, articles, and reports.4 All analysts, however, share one general observation: Terrorist organizations skillfully use the internet and the revolution in telecommunication to advance their operations and broaden the spectrum of use for public information beyond merely enhanced propaganda and the dissemination of terrorizing imagery. New uses of media include the spread of ideology, the justification of violence, recruitment, fundraising, intelligence collection, operational planning, tactical innovation, mission assessment, and more. The technologies gave rise to new forms of militant collaboration and organization, such as peer-production and increased entrepreneurship of individuals and tight-knit groups of young web-savvy activists.

But these tech-driven novelties did not only alter terrorism; they first affected business. The right concepts may therefore not emanate from the gorges of Algeria’s Djebel Aissa Mimoun, but from California’s Silicon Valley. A set of ideas that were developed to understand business in the information age also helps to understand political violence and radical extremism in the information age. Chris Anderson of Wired magazine came up with the concept of the “Long Tail” to explain how in the new business environment the future of commerce was “selling less of more.” He illustrated his argument with companies like Amazon, Netflix, and Apple’s iTunes: These firms made profit out of selling small numbers of previously hard-to-find items to a large number of customers, instead of selling big volumes of a low number of popular products. The high-volume head of the traditional demand curve remained profitable. But the flat tail of the same curve, the low-volume end, would become lucrative as well, driven by increased efficiencies in distribution, manufacturing, and marketing. “Suddenly, popularity no longer has a monopoly on profitability,” Anderson wrote. A similar logic applies to ideologically and politically driven niche violence: It doesn’t require a high volume to survive and endure — that is, a large popular following attracted by a broadly appealing cause. Instead extremists can bring to bear the legitimacy curve’s low-volume end — that is, relatively small numbers of highly-motivated, partly self-recruited, entrepreneurial, geographically dispersed, and diverse radicals, all subscribing to a set of extreme causes without broader popular appeal. New media have popularized the means of production, shrunk the distribution costs, and improved the connection of supply and demand for extreme political, religious, or ideological positions — thus making niche-terrorism viable. The critical mass of people necessary to pass the threshold to a viable terrorist movement has shrunk. The effect of this development is somewhat paradoxical.

The new media, in an ongoing trend, are driving a wedge between terrorism and insurgency: The critical mass necessary to surpass the threshold for a political insurgent movement has not shrunk. Insurgents, even when they started out as terrorists, have traditionally tried — at some stage of their development — to present their cause in a way that attracted followers at the head-end of the popular support. Successful insurgents managed to move more supporters toward the social mainstream. (See figure 1, below. Insurgents would assume goals and tactics at the left side of the x-axis, thereby maximizing the potential for popular appeal.)

Insurgencies tried to win over larger segments of the general population to become a more legitimate political force, sometimes rejecting violence to achieve that goal. The ultimate objective for insurgents was to assume power or realize a political agenda while moderating their extreme positions along the way — an immutable logic that remains true of successful insurgency in the information age, but, paradoxically, has become more difficult to achieve. Because just the opposite applies to global jihadi terrorism: Modern terrorist movements inadvertently move towards the far and flat end of the curve’s tail, away from popular appeal and away from the possibility of consolidating and assuming political power, while escalating their positions into even more extreme ones. And here lies the paradox: More popularly accessible justifications for violence and technical know-how make less popular causes viable. The “democratization” of the distribution and production of ideology and tactics, in other words, lifts up the most fervently anti-democratic fringe groups.

Yes, new technologies and new ideologies have created spectacular advantages for terrorists. But the perks should not cloud the view of the costs. A closer look at al Qaeda’s challenges reveals that the costs of its adaptation to the information age are more impressive and more remarkable than the benefits. Without the internet as a lifeline, al Qaeda today would look very different. The same is not true of Hezbollah, Hamas, or the Taliban. The global jihad and the local jihad diverge more and more.

Support for insurgency

This development, and the conditions that gave rise to it, is a genuinely 21st century novelty. The classic literature on revolutionary war, most of it from the 20th century, has one leitmotif: the material inferiority of nonstate militants vis-à-vis established state authority. The world’s most successful and famous insurgents essentially considered two ways to deal with this key weakness: mass support and tactical innovation. Marx and Lenin tried to rally the support of the working masses against the state, to counter their opponent’s quality with quantity. Mao then applied that theory to China’s “semi-colonial and semi-feudal” conditions; the peasant masses would be the “true bastion of iron,” the chairman wrote. Mao’s writings became probably the most influential pages ever written on irregular warfare — but they needed to be heavily adapted to the peculiar conditions of each theater. For instance, Vo Nguyen Giap adapted Mao’s concepts to Indochina’s anti-colonial war and Amilcar Cabral further adapted it to Africa’s colonial situation. More creative adaptations, deviating significantly from Mao’s ideas and far less successful in practice, were attempted by Che Guevara in Bolivia and by Carlos Marighella in densely populated urban settings in Brazil.

Marxist rebels and French counterinsurgents attempted either to pull off or crush classical local insurgencies — for both, the population was the center of gravity. This paradigm still holds true in local insurgencies today: many groups, some of them Islamist, have a firm local popular base on which they rely heavily. Hamas and Hezbollah are, in this sense, classic insurgent groups with a remarkable track record of success in seizing political power. Seas of supporters waving Hamas’s green and Hezbollah’s yellow signature flags suggest a wide popular appeal in Gaza and South Lebanon respectively. The organizations’ leaders are found in government or parliament buildings behind lecterns, not in camouflage behind guns. Both organizations are not only militias, but have evolved into political parties that provide social and administrative services to their constituencies, largely in line with the classic theory of insurgency. Even the various Taliban groups, if only to a more limited extent, conform to the classic model of an insurgency: The mainly Pashtun fighters have a territorial agenda, and the more pragmatic part of the movement is driven by political (and economic) objectives, which opens the possibility of negotiations. All, however, remain Islamist organizations that employ terrorist tactics against what they perceive as occupation, yet their methods, while still ghastly, are less brutal and radical than those of al Qaeda’s most vicious takfiris.

In continuation of these neo-Marxist and colonial doctrines, and in combination with the optimistic thesis that population security and development in Afghanistan would end terrorism in Europe and America, some have pointed to allegedly tight links between worldwide terrorist cells and the tribal areas in Afghanistan and Pakistan. “Today, virtually every major terrorist threat my agency is aware of has threads back to the tribal areas,” said then cia director Michael Hayden in November 2008, in a statement interpreted by some as proof that jihad retains a popular base. But, more curiously, not only the U.S. Army reads and quotes Mao and Galula at length (Mao is the most-quoted author in the Counterinsurgency manual fm 3-24, with about 20 references, followed by Galula, with about seven). Al Qaeda’s strategists do, too. Abu Musab al-Suri, one of al Qaeda’s foremost strategic masterminds, borrowed heavily from the classic literature on insurgency, most importantly from Robert Taber’s The War of the Flea, on which he gave a series of lectures from 1998 onwards.5 Al-Suri explicitly called Mao, Che, and Giap “the greatest theoreticians in military art.” In good Marxist tradition, he placed his revolutionary hopes in mass support.

The “Architect of Global Jihad,” as his biographer Brynjar Lia refers to al-Suri, summed up his alternative idea as nizam, la tanzim: system, not organization. Al-Suri’s vision for jihad was to have an “operative system” instead of an “organization for operations.” He advocated templates, available for self-recruited activists and entrepreneurs with a desire to take part in the global jihad either on their own or with a group of trusted accomplices. Connections and organizational links between the leadership and units were thus avoided. General guidance replaced specific orders. The glue was “a common aim, a common doctrinal program and a comprehensive (self-)educational program.” Such collectively motivated individual action would open up the possibility for hundreds of thousands of Muslims to participate. An important component in individual jihad is the community of Muslims, the Islamic nation. Al-Suri’s aim was it to create a method

for transforming excellent individual initiatives, performed over the past decades, from emotional pulse beats and scattered reactions, into a phenomenon which is guided and utilized, and whereby the project of jihad is advanced so that it becomes the Islamic Nation’s battle, and not a struggle of an elite.

These individual actions, the would-be revolutionary argued, need to be tied together by a common program, by spreading the culture and the ideology of resistance — the legal, political, and military sciences that the mujahadeen need to fight. These units, al-Suri says, “base themselves on individual action, action by small cells completely separated from each other and on complete decentralization, in the sense that nothing connects them apart from the common aim, the common name, a program of beliefs and a method of education.” Al-Suri, interestingly, had developed his military theory “into its final forms,” as he wrote, in the summer of 2000, before the internet’s interactive revolution.

Al Qaeda, in other words, wished to combine the best of both worlds: the strength of popular support — the Islamic nation’s battle as an equivalent to Mao’s bastion of iron — with the strength of an elusive network without vulnerable hierarchy, composed of self-recruited and self-trained operatives to advance the global resistance. Global jihadi resistance fighters, naturally, like to view themselves as classical insurgents, ingrained in broader society, not as deracinated zealots. They, too, wish to be rooted in the deep soil, not the thinned-out tail.

Support for terror

But tailing off seems to be the future of global terrorism. Al-Suri wanted the jihad to become “the Islamic Nation’s battle, and not the struggle of an elite” — yet this is precisely what jihad is likely to become: The struggle of a small, self-recruited, and self-proclaimed “elite” at the fringes. Two developments have altered terrorism — most visibly the Islamic extremist brand — over the past two decades: Jihad doesn’t have as much popular support as it used to have, and it doesn’t need as much popular support as it used to need.

The first factor is its ideology and embrace of ghastly violence tilting further to the extreme. Throughout its history, even before the rise of the internet, al Qaeda was an insurgent group in exile without a popular support base. It attracted a pan-Islamic global crop of fighters, radical sympathizers from around the world financed it, graduates of training camps operated worldwide, and the al Qaeda leadership planned attacks without geographical limitation. A prominent case illustrates this: Sayed Imam Abdulaziz al-Sharif was a founder of Zawahiri’s al Jihad organization in Egypt that later merged with al Qaeda. A prominent Salafi thinker, al-Sharif was known under the nom de guerre “Doctor Fadl” when working with Zawahiri in Afghanistan. He was one of the guiding forces behind both the violent Islamist insurgency in Egypt during the 1990s as well as the evolution of al Qaeda’s doctrine in later years. In Peshawar in 1988, al Sharif wrote Al-omda fi eddad al-edda, or “The Master in Making Preparation [for Jihad],” then under the name Abdul Qadir bin Abdulaziz. His Master in Making Preparation is a jihadi classic that has been translated into English, French, Turkish, Farsi, Urdu, Kurdish, Spanish, Malay, and Indonesian. It covers in detail, among other things, the religious justification for political violence under the banner of jihad. In the spirit of takfir, or excommunication, the book called for the killing of Islamic autocratic rulers, and everybody who works for them, as infidels if they fail to implement sharia law. Anybody who registered to vote disrespected God’s authority by laying it onto the hands of the people and was thus eligible for takfir, and hence execution.

More than a decade later al-Sharif made an ideological u-turn. In November 2007 he published a ten-volume document called Tarshid al-amal al-jihadi fi misr wa al-alam (“Rationalizing the Jihadi Action in Egypt and the World”) in the Egyptian daily al-Masry al-Youm. In this work, al-Sharif criticizes the use of violence with the aim of overthrowing governments on spiritual grounds: Nonviolence would be religiously lawful and in accordance with the sharia; the potential harm of taking violent action, and the escalation thereof, should be considered against the benefits of peaceful action. Leaders from both major Egyptian terrorist groups, al-Gama‘a al-Islamiya and al-Jihad, had previously renounced violence in a series of debates that largely took place among radicals jailed in Egypt.6 At the end of the 1990s, several leaders of Gama‘a al-Islamiya also renounced violence and declared a cessation of operations, which in turn caused doubt among imprisoned al-Jihad loyalists as well. The Egyptian government, in a permanent struggle to quell radicalism at home, was keen to highlight that the most influential jihadi cleric behind bars had renounced violence.

Sharif’s former comrades-in-arms all had reason to take the threat seriously, and reacted quickly. Predictably, the self-styled resistance fighters jumped on the fact that the publications came out of prison. A press release of Sharif’s upcoming book was faxed to the London-based al-Sharq al-Awsat. Zawahiri, who himself was tortured brutally in Egyptian prisons, replied on July 5, 2007 with a video message spread on the web:

I read a ridiculous bit of humor in al-Sharq al-Awsat newspaper, which claimed that it received a communiqué from one of the backtrackers, who faxed it from prison . . . I laughed inside and asked myself, “Do the prison cells of Egypt now have fax machines? And I wonder, are these fax machines connected to the same line as the electric shock machines, or do they have a separate line?”

The tone should not be misleading. Sharif commands considerable authority among radicals, and the fact that he wrote from prison might give him not less but more street credibility in the eyes of many radicals — certainly more credibility than somebody who never was jailed or in battle. But al Qaeda was only preparing a more substantial response. In March 2008, al-Sahab, al Qaeda’s public relations arm, published the 188-page A Treatise Exonerating the Nation of the Pen and the Sword from the Blemish of the Accusation of Weakness and Fatigue, authored by al-Zawahiri. In it, he questions the publication’s timing and Dr. Fadl’s motivation, and he points out that the text is lacking context, that it is biased, incomplete, inconsistent, unscientific, and that it benefits the Crusaders, Zionists, and apostate Arab regimes.7 This “unraveling” or “rebellion” within the global jihadi movement indicates its shaky support, a trend confirmed by public opinion trends.8

Keen observers of Islamic extremism have long spotted this trend. Angry global jihadis have “none of the social relay points of a well-entrenched movement that might be capable of translating such emotion into civil disobedience — unlike the vanguard Leninist party of 1917, or the Iranian clergy in 1978,” according to Gilles Kepel, France’s other leading voice on Islamic radicalization. “The greatest strengths of terrorism — its suddenness, its use of surprise, and its anonymity — are also its greatest weaknesses when the time comes to reap the political dividends.” Seen in this light, the attack on the United States on September 11 appears not as an act of war of an increasingly mighty organization, but as “the desperate symbol of the isolation, fragmentation, and decline of the Islamist movement.”

The second factor, reinforcing the first, is the extremists’ use of the web. In many ways Europe today is more affected by violent Islamic fundamentalism than the United States. Intelligence agencies on the continent have learned valuable lessons on the nature of the threat. The German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, the Verfassungsschutz, finds that “web-disseminated propaganda guarantees that activists and sympathizers of global ‘jihad’ perceive themselves as part of one coherent movement, even if the participants’ lifestyles and motivations may be highly variant.” Europol’s yearly terrorism report tied this trend to broader social dynamics:

One of the reasons for the attraction of the ideology of global jihad may be that it gives meaning to the feeling of exclusion, prevalent in particular among second or third generation immigrants who no longer identify with the country and the culture of their parents or grandparents, yet feel also excluded from western society, which still perceives them as foreigners. For this group, the idea of becoming “citizens” of the virtual worldwide Islamic community, removed from territory and national culture, may be more attractive than for first generation immigrants.

As a result, the set of recruits in Europe is not only more diverse than in the past, but also younger. The average age of terrorist suspects apprehended in Europe has decreased since 2005. Before December 2003, the average age of jihadi activists arrested was approximately 26 years; the average age of those detained after 2006 was only 20 years.9 Recruits from this younger generation, like most of their age group, are more accustomed to socialization and the creation of trusted bonds through the internet. The Austrian Ministry of the Interior found that, thanks to the web, “radicalization and recruitment become a dynamic two-way process, in which engagement can originate either from the user and/or from terrorist organizations.”

Most intelligence and security agencies come to a similar set of conclusions — and so does the al Qaeda leadership. They are convinced that the media in general and the web in particular are crucial to their cause. At the height of Zarqawi’s violent campaigns in Iraq, Zawahiri reminded his lieutenant to exercise restraint: “more than half of this battle is taking place in the battlefield of the media.” The movement’s leaders decided to do a virtual public affairs blitz in 2007. In September that year, Osama bin Laden appeared in a fresh video, for the first time since 2004. Then several audio messages followed. Simultaneously Zawahiri stepped up his visibility in speeches and tapes that were distributed through al-Sahab. To make it easier for second- and third-generation immigrants in Europe, who often speak only shoddy Arabic, al-Sahab started to use European languages, such as German, French, Italian, and Dutch — but also Turkish, Pashtu, Urdu, and Russian — in order to target other diaspora communities. But al Qaeda overplayed its hand with violence, perhaps as a result of the unbridled zeal of some of its most active self-recruited operatives, both in the Muslim world and the West. In some English-language jihadi forums, for instance, Nidal Malik Hasan’s attack at Fort Hood in November 2009 was celebrated as a victory for al Qaeda. One online commentator, as Jarret Brachman documented, explicitly referred to al-Suri’s writings and praised Hasan for “carrying out the duty, which so many of us are still shirking.” But atrocities, and their real or professed ties to global Holy War, have a polarizing effect. Therefore al Qaeda’s appeal to the broader masses, even considering the peculiarities of humiliated Muslims, will necessarily remain limited or continue slipping. In the information field, the movement does not even have control over who participates and who communicates in its name (in sharp contrast to Hezbollah and to some extent also the Taliban).

Salafi ideology connects a robust albeit outlandish ideological cause to frustrated individuals at the fringe of a large mass of potential supporters. Telecommunication technology is one additional variable that has affected the conditions of this equilibrium. Extremists will continue to find grievances, know-how, money, and each other online, and the barrier of entry into brick-and-mortar terrorism will remain lower than it used to be in the past.

Not winning and not losing

Will success in the Afghan-Pakistan badlands, however defined and however unlikely in the midterm future, end the radicalization of extremists elsewhere and stop global terrorism? Very unlikely. Clearing the Afghan soil would undoubtedly be a very positive achievement — but it would not cut the tail. The lack of hoped-for success in this chaos-ridden region, by contrast, is unlikely to significantly boost al Qaeda’s regional or global appeal, particularly if America’s failure is a result of Afghanistan’s failure to jump through a window of opportunity opened by nato. In short, both success and failure are overrated.

Local insurgencies may still be worth fighting, depending on the geopolitical circumstances and the specific objective. But in the early 21st century, a worrying gap is opening: Counterstrategies have become more population-centric while terrorism has become markedly less population-centric. The consequences of this novel dynamic are as overlooked as they are overpowering: Web-enhanced organizational setups boost terrorism but bridle insurgency. For political violence, the future will likely be recruiting less of more, to paraphrase Anderson. The recruitment market for terrorists is now global. If a movement like al Qaeda recruits a small number of operatives in a large number of countries, it can still manage to survive and do harm. But such a movement will not be able to mature into a global insurgency. Telecommunication technology in combination with Salafist ideology has recalibrated an old equilibrium of armed conflict: It is now easier for terrorists to enter the game and stay in the game, even if they cannot progress. In the future violent extremism will likely be more resilient and more innovative, but less professional, less successful, and ideologically less appealing, although it might occasionally erupt in violence. Jihad will continue to tail Europe and perhaps even the United States, but it will remain a limited threat. Western strategy should not award a prize to global jihadis by confirming their own overblown perception of their military and spiritual strengths. What, then, follows from this?

Counterinsurgency inspired by 19th-century colonial thinkers is a misguided response to 21st-century terrorism; the dichotomy between transnational terrorism and local insurrection did not exist in the 1800s. The United States and its nato allies should therefore state clearly that al Qaeda cannot be “disrupted, dismantled, and defeated” in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Neither the West nor jihadis can win — or lose — this war. Al Qaeda wanted to become a global insurgency but failed; it is now stuck at the tail. The better response seems to be prudent domestic counterterrorism policies — e.g., quiet and invisible intelligence, law enforcement, and police work, along with prudent expeditionary operations. This is already happening to a remarkable extent. But we should not delude ourselves: The absence of a major terrorist attack in Europe and the United States since 2005 is notable not because “we are fighting them over there,” but despite the two wars that have motivated scores of militants to join the global jihad — most in Muslim countries, many in Europe, and some in the United States. The destruction of Afghanistan’s training camps in 2001 and 2002 was certainly a helpful achievement, as were the assassinations of top terrorists in Pakistan and elsewhere. Counterterrorism, in short, seems to work, both defensively at home and offensively abroad. It is important to note that the choice is not one between counterterrorism or counterinsurgency, but between counterterrorism flanked by counterinsurgency or not. Then the question is: When does counterinsurgency add value to counterterrorism?

The answer is complex. First, insurgency and terrorism should be properly kept apart, even if global jihadis continue to rely, at least partly, on some local insurgencies. Groups as different as Hamas, Hezbollah, the Taliban’s various offshoots in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and al Qaeda and its regional franchises and allies are often named as wholesale enemies. The imperative, to the contrary, should be to disaggregate and to differentiate between such groups. And even within these groups differences abound: The Taliban itself is a diverse cluster, with local subgroups and diverging tribal, economic, political, and personal interests. The same applies across time: Al Qaeda today is very different from al Qaeda eight years ago. So, too, the Taliban. It is vital to highlight and exploit disparities, not to ignore them or even help remove them.

The most important conclusion is a more general one. The level of terrorist aggression cannot be eliminated for good, neither through successful counterterrorism nor through successful counterinsurgency. But the threat can be managed and contained through a sophisticated cost-minimization strategy that pushes the level of violence down and the popular support for terrorism to the tail — yet it will not go to zero and it will not end. Victory and defeat are concepts that assume such an end point, as does most of Western strategic thought. Many such ideas, therefore, seem out of place. If the attempt to occupy, transform, and “re”-construct large swaths of previously ungoverned or badly governed land in Afghanistan, Iraq, or elsewhere does not bring the desired long-term results — and perhaps even contributes more to the cost than to the benefit side — ambitions will have to come down and strategies will have to change. Like crime, terrorism may be a form of violence that can only be contained, deterred, and denied, but not wiped out.

1 Bruce Hoffman, “From the War on Terror to Global Counterinsurgency,” Current History (December 2007); David J. Kilcullen, “Subversion and Countersubversion in the Campaign against Terrorism in Europe,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30:8 (2007).

2 David Kilcullen, The Accidental Guerrilla (Oxford University Press, 2009).

3 For the original quotes, see Hubert Lyautey, Du rôle colonial de l’armée (Armand Colin, 1900), 11; Hubert Lyautey, Lettres du Tonkin et de Madagascar: 1894–1899 (Armand Colin, 1921), 635; and Joseph-Simon Galliéni, Neuf ans a Madagascar (Librairie Hachette, 1908), 326.

4 Daniel Kimmage, “The al Qaeda Media Nexus,” rfe/rl Special Report, 2008; Thomas X. Hammes, The Sling and the Stone: On War in the 21st Century, (Zenith Press, 2006); Gabriel Weimann, Terror on the Internet: The New Arena, the New Challenges (The United States Institute of Peace, 2006); Michael Scheuer, “Al Qaeda’s Media Doctrine: Evolution from Cheerleader to Opinion-Shaper,” Terrorism Focus 4:15 (2007). For a more detailed discussion, see Thomas Rid and Marc Hecker, War 2.0 (Praeger, 2009). As a resource for current trends in “the forums,” see Thomas Hegghammer’s blog Jihadica.com.

5 Brynjar Lia, Architect of Global Jihad: The Life of al-Qaida Strategist Abu Mus’ab al-Suri (Columbia University Press, 2008), 226.

6 Lawrence Wright, “The Rebellion,” New Yorker (June 2, 2008).

7 Abdul Hameed Bakier, “Al Qaeda’s al-Zawahiri Repudiates Dr. Fadl’s ‘Rationalization of Jihad,’” Terrorism Focus 5:17 (2008).

8 Peter Bergen, and Paul Cruickshank, “The Unraveling,” New Republic (June 11, 2008); Wright, “The Rebellion”; Michael Scheuer, “Rumor’s of al Qaeda’s Death May be Highly Exaggerated,” Terrorism Focus 5:21 (2008).

9 Marc Sageman, Leaderles Jihad (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 111.