- Economics

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

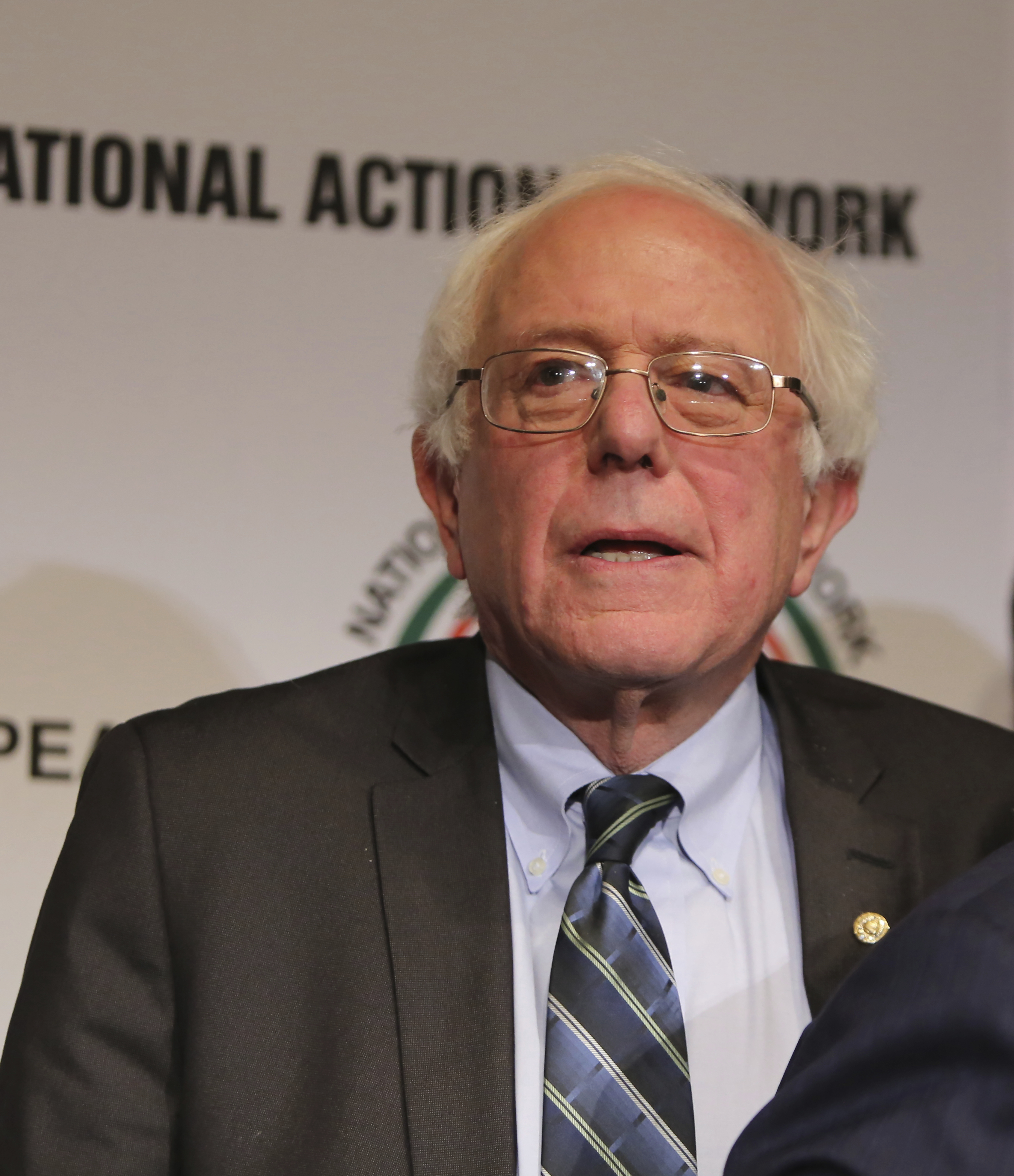

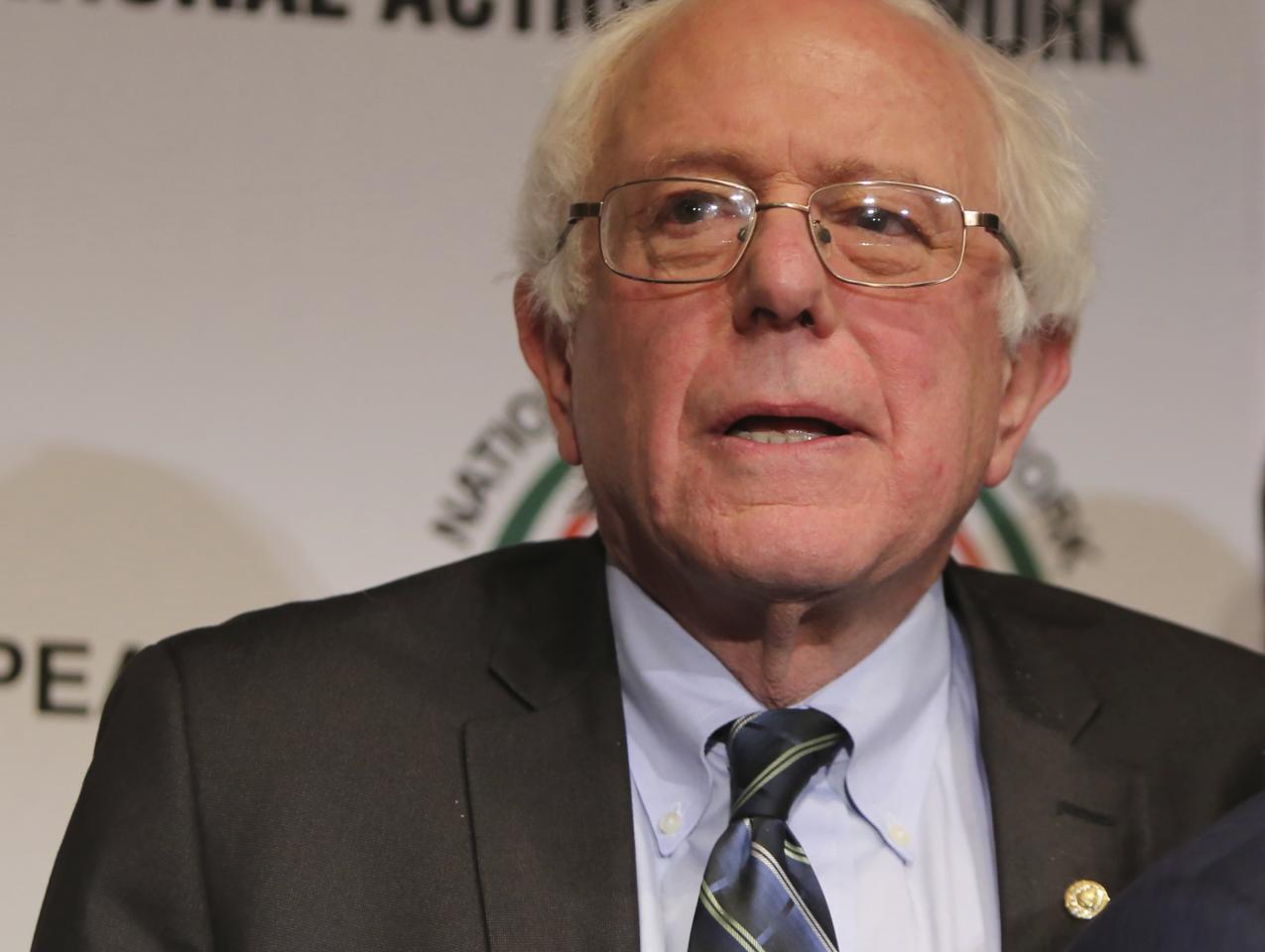

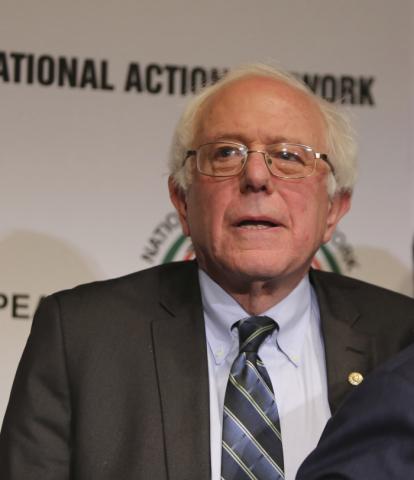

As his campaign roars into New York State, Bernie Sanders has been on a roll. He has won eight of the last nine primary contests, most recently the ones in Wisconsin and Wyoming. His impressive performance has emboldened him to take on Hillary Clinton in her adopted home. Sanders has attracted wildly enthusiastic audiences by pushing his program of economic populism. He loudly proclaims that, unlike Clinton, he has never received support from Wall Street or corporate interests—and that his impressive financial support comes from tens of thousands of small contributors, each of whom shares his vision. If elected president, he points out, he would be held accountable to these supporters and will make good on his program that includes massive tax increases largely targeted at the super rich. The effectiveness of his campaign is measured by the extent to which it has forced Hillary Clinton, not a person of deep principle, to veer sharply to the left in order to secure the nomination, after which, if successful, she will have to lurch back to the center in order to gain the presidency. He is the populist hero. She has become his pale imitator.

But the populism that both candidates trumpet is flawed. Any complex political issue will always present a fair share of economic and social trade-offs, which makes it imperative for a serious candidate to see both sides of a given question. That degree of caution, however, is nowhere present in the position papers of either Sanders or Clinton, neither of whom ever addresses the downsides of their proposals. Like most populists, both are far better at denouncing the current state of affairs than in explaining the plusses and minuses of their own plans.

In this regard, income inequality is for both candidates the bellwether issue of our time. On his website, Sanders begins his own treatment of the topic by trumpeting the high level of income inequality in the United States, a point on which Clinton quickly follows suit. But there are only two ways in which to reduce the level of income inequality: either by lifting the bottom earners up or by pulling the higher earners down. Both candidates, it seems, are insistent in trying the latter route. But both ignore the simple truth that it is a lot easier to destroy wealth by government fiat, and far harder to create it, given the law of unintended consequences. Sanders and Clinton suffer from the fatal delusion that they can ignore the responses that private parties will take when hit by a new round of taxes and regulations.

To give but one example, the Obama Administration’s Department of Labor has proposed increasing the number of workers covered by the overtime provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act. It will extend its protections to all workers who earn under $50,440—more than double the current level of $23,660. Needless to say, this proposal gets Clinton’s support as another example of “fair growth.” But as Donald Boudreaux and Liya Palagashvili point out in their recent Wall Street Journal Op-Ed, the most likely effect of this policy is that employers will reduce the base wage of covered workers to offset the increased overtime costs, at which point everyone will be left worse off than before. As is usually the case, “fair growth,” like “fair trade,” turns out to be an oxymoron.

The explanation for this outcome runs as follows. Any shift in required compensation formulas, let alone one that could impact as many as 5 million workers, is costly to put into place, and those compliance costs could require firms to scale down their operations, raise their costs, and ultimately result in them receiving a reduced net income, which also reduces net revenues to the government. But nothing will be gained from these increased costs. Instead, the impacted firms will take steps to reclassify workers in ways that will minimize the brunt of the burdens, or introduce new technologies that will reduce the number of jobs that are subject to overtime wages. The one thing that will not happen is a simple wealth transfer of dollars from firms to lower or middle-income employees. Instead, the size of the pie will shrink and the distribution of those losses will be hard to project in advance, given the many different firm structures to which the rule applies.

Nor is it sensible to justify this sharp bump by noting, as is surely the case, that the number of workers covered by these overtime rules has dropped from about sixty percent in 1975 to under eight percent of workers today. Before that argument can be made, it is necessary to explain why the high level of overtime wages put into place 40 years ago under the FLSA counted as a social benefit when it reduced flexibility in labor markets. From its inception, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) created a massive interference in the operation of labor markets, to which the proper social response is to slowly shrink via administrative inaction the number of workers who are affected by its provisions. The same argument applies to virtually every proposed labor reform that seeks to provide workers with wages that are not backed by productivity gains, which only free markets, not government mandates, can supply. It is easy for both Clinton and Sanders to lament the fate of the shrinking middle class. But both of them need to recognize that their own aggressive policies that interfere with labor markets will only compound the difficulties that they see.

The same kind of woolly thinking is behind both of their proposals to deal with the unfair distribution of income through steeper progressive taxation. The typical indictment begins by noting that the ever larger share of wealth that is taken up by the top one percent, or even the top one-tenth of that one percent. But it is quite another thing to supply the explanation for why this has happened. In this regard, no one factor begins to explain the consistently slow rate of growth in the United States. But it is at the very least unnerving that the rise in regulation and taxation have been followed, as the night follows the day, by lagging overall growth and the declining income of Americans clustered in the middle of the income distribution. But it is a far cry from that to say, as Sanders does, that “Wall Street and the billionaire class has [sic] rigged the rules to redistribute wealth and income to the wealthiest and most powerful people of this county.”

If true, these billionaires have not been very good in executing their master plan, given that their share of public expenditures is far higher than their share of income. The top one percent earns 17 percent of the wealth in the United States, but it also pays about 45.7 percent of all individual income taxes, a fact that never made it into the Sanders’s broadside. Yet, just think what would happen if these incomes fell in response to higher levels of taxation. Our entire system of redistribution depends on not killing the goose that lays the golden egg. However, the effort to squeeze a few more percentage points of income from the highly wealthy runs the risk of reducing their income, thereby eliminating the high marginal tax rates paid on their current top dollars of income. At present, there is, if anything, good reason to reduce taxation rates in order to expand the tax base, yielding both higher incomes for current citizens and more revenues for the government.

That is not likely to happen with either the individual tax rates or the U.S. corporate tax rates, which are the highest in the industrialized world. Corporations, like individuals, respond to incentives, making it all too understandable why large American ones like Pfizer are seeking through inversions to set up operations overseas. As Pfizer CEO Ian Read notes, inverting is necessary to allow them to compete on even terms for investments dollars in the United States. Just allowing the tax-free repatriation of foreign dollars already taxed into the United States would put an end to the inversion movement. But no, the fatal miscalculation to tax corporations on their income earned overseas, a policy unique to the United States, is defended by Democratic populists, even as it puts American corporations at a comparative disadvantage in their home court.

More generally, it is a deep danger sign when any country seeks to limit the exit options of its citizens and corporations. Squelching exit options is a sure sign that the domestic scene is out of whack for the United States in 2016, as it was for East Germany in 1961. The point here is no different from that with free trade, and the fear that American corporations will send jobs overseas while unemployment rates are high in the United States. It is not the case that the rules dealing with domestic labor markets—as with the recent change in the FLSA overtime threshold show—are ideal, when they become more dysfunctional with each passing day. It is that all too often, the only way to remain in business at home is to move some jobs overseas, or face the serious risk of bankruptcy or massive contraction.

At this point, we can explain why the enormous appeal of economic populism is also our greatest danger. The constant attacks on the richest and most productive portion of the population insulate the rest of the system from the intelligent criticism that it needs in order to reach higher levels of performance. There is a real fork in the road. The populists believe that the actions of private firms and individuals are the source of our national difficulties, such that another round of regulation or a new set of taxes is the best way to bring the current malaise to an end. And so the Sanders campaign can note the declining median income of both male and female workers, and conclude that all of this is “unacceptable” and “has got to change.” But indignation is not a substitute for intelligent prescriptions, especially when the wrong populist diagnosis will lead to the wrong proposed cure and make the situation even worse.

The populist view of the economic universe is that the United States has not regulated or taxed itself enough to secure the appropriate level of income equality and social justice. Politics aside, the correct view is exactly the opposite.