- Law & Policy

It is commonly said that the next presidential campaign begins the day after the midterm elections are over. If that is so, then Donald Trump, true to style, has gotten off to a disastrous start with his opening gambit for the 2020 campaign. First, he fires—excuse me, requests the resignation of—Attorney General Jeff Sessions, whom Trump could not abide because of Sessions’ decision to recuse himself from oversight of Robert Mueller’s investigation into possible Russian interference in the 2016 election. Trump then compounded his own misery by announcing his appointment of Matthew Whitaker, Sessions’ Chief of Staff at the Department of Justice and alleged Trump “loyalist,” as Acting Attorney General until a permanent replacement for Sessions is confirmed by the Senate.

In one of the finer ironies of a most unsubtle age, progressive forces have come out in force to protest the removal of Sessions and to deplore the appointment of Whitaker. The past few days have witnessed mass protests to keep Mueller in place; 18 state AGs calling for Whitaker to recuse himself from the Mueller investigation; an open letter from members of the legal profession condemning “Trump’s outrageous attempt to undermine the investigation into possible wrongdoing” in the 2016 election; and Trump’s toe-to-toe press conference confrontation with CNN reporter Jim Acosta—only for Trump to revoke Acosta’s press credentials, with a promise of more to come. The entire episode has not been lost on the electorate. The lackluster 2018 showing of the Republicans in a strong economy bodes ill for the president. Trump remains his own worst enemy, and for what?

Apparently, to give large amounts of ammunition to his progressive critics. It did not help that Whitaker is on record in 2017 as a strong critic of the Mueller investigation, which he has condemned as both “ridiculous” and “a little fishy.” He has also been a fierce critic of Marbury v. Madison, the landmark 1803 Supreme Court case cementing judicial supremacy in the United States, for which he has promptly been denounced by, among others, Ruth Marcus in the Washington Post as a “crackpot.” A lot of what Whitaker said on Marbury may make good sense for an outsider, like me, but not for anyone in politics. Why would a potential AG defend positions that put him in obvious tension with his official duties?

To keep matters in perspective, here is a quick overview of both of Marbury v. Madison and the Mueller imbroglio.

Let’s take Marbury first. It is possible—indeed correct—to insist that Chief Justice John Marshall consciously introduced a bit of ambiguity into constitutional law when he announced in his opinion for the Court that “it is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.” True enough. But at the same time, Marbury needed for its resolution, not judicial supremacy, but only the far more modest proposition that Congress cannot foist on the Supreme Court the duty to decide a matter that falls outside of its constitutional competence. The far greater power of judicial supremacy over the other branches of government was only definitively established as late as 1958 in Cooper v. Aaron, a critical case in the struggle to end racial segregation in the South. But who cares? Whatever the merits of Marbury in 1803, judicial supremacy has become such a fixed part of the American constitutional tradition that it is unwise for anyone—and I mean anyone—in public office to challenge that practice. The lone exception was Abraham Lincoln, a determined foe of judicial supremacy, in his effort to limit the influence of the pernicious 1857 decision of Chief Justice Roger Taney in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which held that African Americans were not, and could not become, citizens of the United States because of their supposed racial inferiority. Of course, the Court’s 1954 holding in Brown v. Board of Education, which ordered the end of racial segregation in public schools throughout the United States, falls on exactly the other side of the issue where it has been enthusiastically embraced.

This constitutional detour is, however, less important than Trump’s chronic overreaction to the Mueller investigation. Part of the problem was of his own doing. He should have never appointed Jeff Sessions as Attorney General in the first place. It was just asking for trouble to reward a faithful political supporter with a position that requires at least some independence from the president. Something bad was bound to turn up, and when Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation, he earned the undying enmity of his boss.

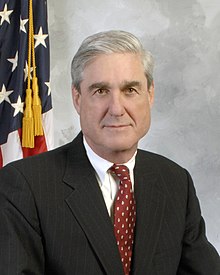

His overreaction to one side, Trump does have a legitimate beef with the entire operation. It makes eminently good sense, both then and now, to say that then-Acting Attorney General Rod Rosenstein should have never appointed Robert Mueller on May 17, 2017 to run an investigation guided by two possibly inconsistent charges. The first involves investigating “(i) any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump” and the second “(ii) any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation.” The first tips the scale unfairly against the President by foreclosing an investigation of any connection that the Russian government might have had with the Clinton campaign. At the same time, it is unclear whether the second covers the preparation and use of the notorious Steele Dossier—unless that counts as a collateral matter that arose out “directly” of the investigation. But the terms of the authorization do not require Mueller to pursue that last path, which would have led him to ask why both Rosenstein and Comey signed search warrants submitted to the FISA Court, dealing with foreign surveillance, to continue their investigation of Carter Page without revealing that these items had their origin in documents prepared at the behest of the Democratic National Committee. For over 18 months, the probe has had a built-in partisan slant that Mueller has done nothing to dispel.

Worse still, Rosenstein ignored Mueller’s close ties to Jim Comey, whom the president fired as head of the FBI on May 9, 2017—just ten days before Mueller’s appointment. Comey was likely even then to become a key figure in the probe, given the FBI’s oversight of the entire Russia investigation in late 2016 and the possibility of obstruction of justice charges against the President. No conflict should be tolerated in matters of such importance. Rosenstein was obligated to appoint a neutral party with impeccable credentials but with no actual or apparent conflict of interest. Mueller does not fit that bill.

It is ironic, but true, that none of this matters in the current political debate, which treats Robert Mueller as an immovable and incorruptible figure, beyond politics and thus beyond removal by the President or the next Attorney General. Firing Mueller would invite new charges of obstruction of justice against President Trump, even if ordinarily the president has constitutional authority to fire any senior cabinet member. That said, Mueller’s performance of this investigation for the past 18 months has been a total bust. The only criminal actions he uncovered do not involve any underlying links or cooperation between the Trump campaign and the Russian government. Nor is there any probe, either by Congress or an independent party, that has come upon evidence that Mueller and his minions have missed. By recent count, Mueller has come up with 32 indictments or plea bargains, many against Russian nationals abroad. Sadly, his dicey plea bargains with George Papadopoulos and Michael Flynn were for lying to the FBI, not for any underlying criminal conduct.

This meager haul suggests that Mueller’s 18 months has exhausted all leads against the Trump campaign. The most powerful weapon left in his investigatory arsenal is to take the deposition of Donald Trump—the least coachable witness in the history of Western Civilization. His lawyers should never, ever, let him verbally answer any question under oath; perhaps they could tolerate some written interrogatories as part of a political compromise. Even then, that should only occur if some independent evidence is presented linking the President to Russian agents. Navigating these treacherous waters explains why some even-handed oversight of the Mueller investigation is desperately needed. Politically, the next Attorney General cannot sack Mueller. Nonetheless, quieting those waters, he or she could ask some very tough questions. The new AG could demand that Mueller report on his progress to date, identify unexplored areas of investigation, consult with the AG before bringing any new indictments, and set an end date to the investigation. Checks and balances are always in order.

In 1988, the late Justice Antonin Scalia had one of his finest judicial moments in Morrison v. Olson, in which he attacked the untethered adventures of the then-special prosecutor Alexia Morrison in her hot pursuit of Ted Olson for giving “false and misleading testimony to a congressional subcommittee.” Scalia called things as they were. That investigation was about one thing: “Power.” Sometimes power is artfully disguised, he noted. “But this wolf comes as a wolf.” The institutional arrangements have changed somewhat since then, but the power dynamics remain the same. An independent AG is needed to rein in both the President and Mueller—and to bring this investigation to a timely and proper conclusion.