The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) successfully held a referendum on a new constitution in December 2005, thus passing another milestone in its agonizingly slow transition from war to peace; from internal division to governance under one central authority; and, it is hoped, from dictatorship to democracy. This transition has now lasted 15 years, and many obstacles still face the country before it can become stable, united, and governable. During this period of transition the DRC faced three wars that involved invasion by neighboring states, civil war, and foreign militias operating within its borders. By far the most painful, indeed horrific, aspect of this period has been the human toll: Reliable estimates indicate that around four million people have died and three million have been displaced as a result of these wars.

Why has this catastrophe received so little attention from the media and, until very recently, from the international community and the U.S. government? I don’t have a good answer except to suggest that these conflicts are extraordinarily complex and that it is impossible to reduce them to a simple formula of “bad guys fighting good guys.”

How did this catastrophe come to pass?

THE LOST YEARS

In the 1990s two developments started the DRC on the downward spiral that ended up in war, death and displacement of populations, collapse of social services, plundering of natural resources, and so on. The first was that, after more than 30 years of corrupt and dictatorial rule, President Mobutu began losing his grip on power, in large part because the West no longer supported him after the end of the Cold War. The second event was the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsi population of Rwanda in 1994 by the Hutu-dominated government and its army and militia. As a result of the genocide, more than one million Hutu “genocidaires” and their families fled to the DRC, where they were lodged in U.N. refugee camps. Overwhelmed by the number of refugees, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees allowed the camps to be erected on the border with Rwanda. Because the very leaders who had perpetrated the genocide controlled the camps, they were used to launch attacks against the new, Tutsi-dominated, government of Rwanda. The new Rwandan leadership, of course, found this situation intolerable and repeatedly asked the international community to take control of the camps, disarm the militia, and prevent attacks against Rwanda.

| The progress in the last few years would not have been possible without the presence of the U.N. peacekeeping force (MONUC) in the Congo, currently operating at a cost of more than $1 billion a year. |

For two years these appeals went unanswered, so in 1996 Rwanda took the matter into its own hands. It invaded the DRC and destroyed the Hutu camps. Close to 800,000 Hutus walked back into Rwanda, but the militia (with some civilians) moved west into the DRC, where Rwandan and Ugandan forces pursued and sometimes massacred them. Soon, Angola joined the Rwandan-Ugandan invasion forces; all three nations then helped create and support a Congolese anti-Mobutu revolutionary force. Thus, the first Congo war was launched; within eight months Mobutu’s army had been defeated, Kinshasa captured, and the leader of the “revolution,” Laurent Kabila, installed as president.

Although initially popular, Kabila soon disappointed both his foreign sponsors and many of his Congolese supporters. The Congolese resented his ruling in a dictatorial fashion. For many years a substantial, nonviolent group opposed to Mobutu had fought for a more pluralistic, democratic order in the DRC. Kabila treated the leaders of this movement with contempt. The Congolese also increasingly resented Rwandan influence on Kabila. He also alienated Western powers by refusing to cooperate with a U.N. mission sent to investigate the massacres of Rwandan Hutus and by adopting anti-Western stances reminiscent of the 1960s.

| Why has the Congo catastrophe received so little attention from the media and, until very recently, from the international community and the U.S. >government? Perhaps because it can’t be reduced to a simple formula of >“bad guys fighting good guys.” |

By the summer of 1998, Kabila’s relations with his foreign sponsors had seriously deteriorated—especially those with Rwanda. Using the formal sovereignty that was at his disposal as president of an independent state, Kabila told the Rwandans to pack up their army and leave. Rwanda complied but, along with its ally Uganda, reinvaded the DRC. Attempting to repeat a formula that had worked very well in 1996, the Rwandan-Ugan-dan alliance created a new Congolese “revolutionary” movement that challenged the legitimacy of the Kabila regime. In a surprising and momentous action, however, Angola—along with Zimbabwe and other African states— decided to switch sides, intervening militarily to support Kabila. The second Congo war had begun.

By mid-1999, the war had become a military stalemate that resulted in successful negotiations not only among the various Congolese military and political factions but also among the opposing foreign armies fighting in the DRC. The Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement rested on four pillars: (1) a cease-fire zone between the areas of the DRC controlled by Kinshasa and those controlled by different rebel groups; (2) an agreement to bring all Congolese political, military, and social forces together with a view to creating a transitional national government leading to elections and the installation of a democratically legitimated government with a new constitution; (3) disarming and repatriating the foreign militia based in the DRC that were fighting the governments of the states they originated from; and (4) the creation of a U.N. force with the task of observing the cease-fire and—later—more broadly restoring peace and security.

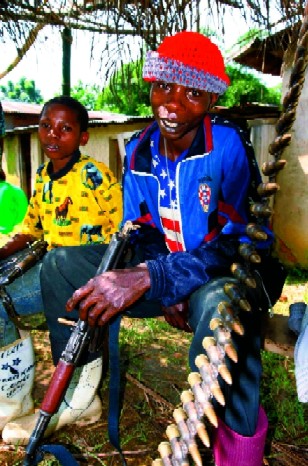

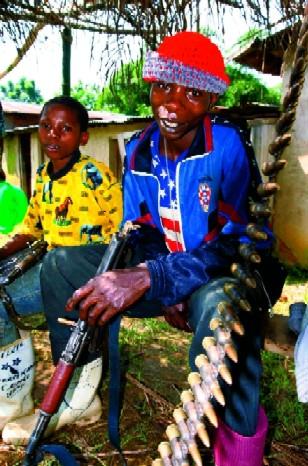

It took four years for most, but not all, of the key components of Lusaka to be fulfilled. In the meantime, a massive, new, third Congo war broke out. The rebel-controlled areas in eastern DRC aroused profound resentment among the local population. They viewed the rebel administrations as puppets of foreign invaders. These sentiments resulted in a violent, guer-rilla-type mobilization against them by militia generically called the Mai Mai. Following the principle of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” the Mai Mai made common cause with the Rwandan and Burundian Hutu militia operating in eastern DRC. Kinshasa saw an opportunity to weaken the rebel administrations in the east—as well as their Rwandan and Ugandan sponsors—and thus gave military, financial, and political support to this anti–Rwanda/Uganda alliance. Neither the first nor the second Congo war lasted as long or caused as many casualties as this third conflict. Unfortunately, during most of these four years the international community and the United States largely ignored that third war; indeed, it continues in somewhat muted form to this day.

WHERE THINGS STAND

Both the main armed and nonarmed political and military forces contending for power inside the DRC have come together and, in 2003, formed a transitional government. Since then, a new constitution has been drafted and passed by a popular referendum. An independent electoral commission has been created that successfully registered more than 20 million voters and organized the recent referendum. Different Congolese armed groups have been formally—but not as yet actually—unified under the transition government. Some advances have been made in disarming and repatriating foreign militia to their countries of origin, but many still remain. In general, the eastern DRC continues to be an arena of conflict and violence.

The first of a series of elections in the DRC is scheduled to take place in June or July 2006—initially for president and national assembly. If one of the approximately 50 candidates for president does not obtain an absolute majority, a runoff round with the leading two candidates will take place sometime in the fall. The national assembly election will employ a system of proportional representation. Provincial elections—important because the provincial assemblies will elect national senators—will also take place in the fall. If all goes well, by October or November the new president will have been inaugurated and the different assemblies will have been installed. This progress would not have been possible without the presence of the U.N. peacekeeping force (MONUC) in the DRC, currently operating at a cost of more than $1 billion a year.

The next few months—with the prospect of transparent and fair elections, a new spirit of national reconciliation, and a new governmental legit-imacy—hold the promise of a new start for the DRC. Social, health, educational, and economic conditions have hit unacceptable lows. Apart from the emergence of a new leadership legitimated by elections, the violence in the east has to be controlled and diverse armies and militia have to be integrated into a unified, national army.

Hopefully, the Congolese will see 2006 change their fate for the better.