- Law & Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Regulation & Property Rights

Editor’s note: This is the second installment in a series of four essays by the author on the ongoing efforts in Congress to reform the U.S. patent system. The first essay, "The Perils of Patent Reform," can be found here. The third essay, "Patent Reform Goes Haywire," can be found here. The fourth essay, "File First, Invent Later?" can be found here.

The first installment of this series explored the basic analytical framework behind debates about patent reform. The details of the patent system that are being discussed in Congress are not likely to lead to important large shifts in overall rates of invention and patenting. Rather, the America Invents Act—pending in Congress—will likely impact the rate at which inventions are actually brought to market—commercialized—and the extent to which the large successful firms in our economy will be joined by, and face competition from, large numbers of small and medium-sized firms.

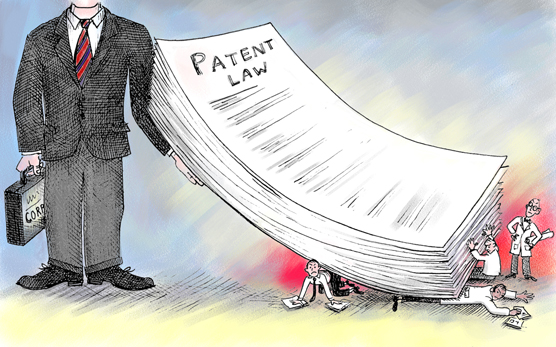

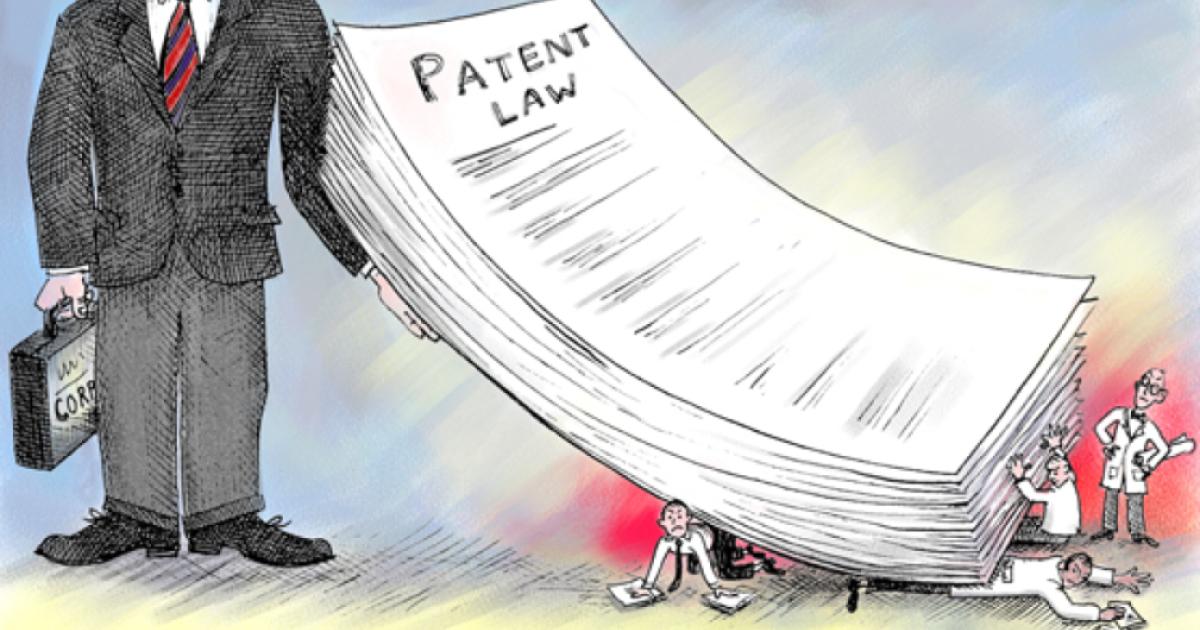

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

The Patent Office: Where Less is More

Many good and hard working people work in the patent offices of the world, including our own. They are public servants doing important work. It may even make sense to give the Patent Office more control than it presently has over its own financial operations—a topic called fee-setting authority in the bill presently before Congress.

But a celebration of the true wonders of our Patent Office—both its examining corps and its leadership—does not mean it should be beefed up, as the pending bill would allow. Even a patent office brimming with Einsteins—remember, he actually started his career in one—would be no more effective even if it were allowed to deploy ten times the number of hours it presently does to examining patent applications. What is worse, it would do great harm.

To give some context, consider this convenient comparison: even taking into account the depths of the 2008 economic crash, our securities markets are the largest in human history and yet their flagship regulatory body, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), has long operated with about half the staff and half the budget as the U.S. Patent Office. Despite the SEC’s important duties to protect a vast base of inexpert lay consumer investors, even the populist FDR administration expressly rejected suggestions that the agency should do searching examinations of its filings. Our securities system is premised on disclosure, not merit review.

Patents are most certainly not directed at unsophisticated, lay, consumer audiences. They are for technological, legal, and business experts. These experts look to the Patent Office to merely conduct a decent first pass at assessing patent validity while maintaining a clear, centralized, and easily searchable repository of the patent records.

It makes little sense for society to invest heavily in the vast expenses it would take to conduct factually complete examinations of patent applications, as proponents of the pending bill could be contemplating. Most patents do not matter to anyone and it often take years for anyone in society to make good decisions about which patents will matter to any significant degree. But even for those patents that do matter, it makes most sense for decisions about the validity of those patents to be made in federal court litigations, rather than in the byzantine and politically influenced administrative procedures of the Patent Office. While the patent system of today already has too many bad procedures for challenging the validity of a patent, the proposed bill adds even more.

A patent should be challenged in court, not in the U.S. Patent Office.

Challenging a patent in court is a process that makes sense, because that’s where actual historical and technological facts can be tested in front of a jury with the aid of fair and established rules of evidence and procedure. While bad faith litigation can be a serious problem, a direct way to mitigate that problem, which is noticeably absent from the present bill, would be to allow courts to award attorneys fees and other actual damages against a party, on either side, who presses an argument in court that he has no good faith basis for thinking should win. These damages could even be trebled in egregious cases.

Alleged infringers rightfully worry about the in terrorem impact of the high cost of baseless litigation and the way it can allow plaintiffs with bogus patents to shake down large companies for large numbers of expensive settlements. And small inventors rightfully worry that baseless arguments about invalidity could bleed patentees dry through years of litigation costing millions of dollars per year.

Such a system of bad-loser-pays is used with some success in several other areas of U.S. law., and in many areas of law in the U.K. There are good reasons to think it would directly address serious concerns voiced by those on both sides of the patent debate. It shouldn’t be expected to decrease the frequency of litigations; but it should reasonably be expected to decrease their overall length and cost. That’s because when both sides elect to file in court, it triggers the rules governing evidence and procedure that allow the parties to exchange the appropriate evidence with their opponents while putting them on notice that continuing on the same path brings with it real risk.

Even in the allegedly pro-patent days of the key U.S. court of appeals that heard patent cases—the "Federal Circuit,"—that court did not resist awarding fees against patentees, their trial lawyers, and their appellate lawyers when appropriate, as in the 1997 Judin decision. That court also did not resist calling out by name those lawyers who engaged in bad faith approaches to litigation by writing and then citing to baseless opinions of counsel, as in the 1998 CellPro decision.

In addition to litigation, the existing patent system has two other infamously dysfunctional administrative procedures for testing the validity of an issued patent. In so-called ex parte reexamination, patentees are king because they are the only ones who get to participate in the process. Unsurprisingly, patentees are notorious for using this procedure to try to white wash their own patents; and infringers are routinely advised to save their killer evidence of the prior art for other proceedings.

In response to these concerns, Congress passed a so-called inter partes reexamination proceeding that is adversarial in nature, allowing both the patentee and the party challenging validity to participate. And unsurprisingly, this procedure has been abused as well. Alleged infringers routinely dig up new proxy parties and new arguments, while evidence about prior art can especially keep the best patents in a purgatory of perpetual reexamination.

A politicized patent system will further entrench those companies with the largest lobbying shops on K Street.

Shockingly, the proposed bill not only keeps these old administrative procedures in place, it also adds at least two additional ones, known as post-grant review and supplemental examination. One of the so-called selling points of these administrative procedures is that they are faster and less expensive than civil court litigation. This of course reveals the true agenda of those behind the pending bill. The mechanism they use to increase speed and decrease cost is to depend less on the very time consuming and expensive process of getting factual evidence about the prior art, such as particular lab notebooks and sample products. Rather, the proposed procedures would allow the administrative judges and examiners to rely on their own technological expertize to simply assert what they view the historical record to be in a given area of technology.

Under established principles of administrative law, the more an administrative agency gets such substantive adjudicatory power, the stronger its claim for special administrative deference is, if its decisions are ever challenged in court. That means the new procedures are more than just new procedures. They seriously bolster the claim that the Patent Office has been pursuing for several years now, which is for its decisions to be given the type of high deference we reserve to the political agencies designed to implement executive policy.

However supportive or critical one may be of the politicking of executive branch agencies, the role of politics in the patent setting is particularly suspect for at least two key reasons. First, even if you think politics is great, it changes with administrations. That kind of change fundamentally erodes the long term investing we all want to see in property rights. This brings up the second key reason why politics and patents shouldn’t mix: property rights are at their worst when they swing with the political winds. In such a scenario, the only type of investors they will draw will be those who are the most politically influential.

Fears about pure political influence driving outcomes at the Patent Office are not without foundation in recent history, under both Democratic and Republican administrations. The elimination of effective patent protection for computer software through the Supreme Court’s 1972 Benson decision was the direct result of intensive influence wielded by Nicholas Katzenbach, who became general counsel of IBM in 1969, over the U.S. Department of Justice, which he formerly ran as Attorney General during the Kennedy/Johnson Administration. And a similar influence was applied, albeit ultimately unsuccessfully, during the first Bush administration, in the lead up to the 1994 appellate court Alappat decision. The Patent Office Commissioner had made the decision to reconstitute the office’s internal Board of Appeals to hold a rehearing before a specially packed Board designed to reject the patent on a type of software.

The bill expedites patent applications for innovations that are in the public interest, like so-called "green technology."

The bill now pending before Congress contains explicitly political components. One provision shamelessly offers expedited processing of patent applications for those technologies deemed by a given administration to be more in the public interest than others. The current administration has already announced that this means a preference for so-called "green technology"—but just imagine the outrage when a Republican administration favors, say, the technologies of the defense or oil industries.

Proponents of the pending bill sell these provisions in the name of helping small businesses get more tailored examination rates to suit their particular needs. But in any system of limited resources, expediting the examination of one entire class of applications will only slow the process down for other classes. Also, why would anyone versed in even rudimentary political economy expect that in a commercial area of law like patents, a government bureaucracy would bend mostly toward the will of the smallest market participants over the largest? Besides, the patent holdup nightmares that those same large industrial players complain about would only worsen in a system that increases the delays within the Patent Office for large classes of applications.

A politically enhanced patent system is one that will further entrench those companies with the largest lobbying shops on K Street. That turns a body of law designed to promote competition into one that frustrates it.

Having already explored many reasons to be skeptical of Congress’ reform efforts, you might be wondering whether the rest of the America Invents Act continues in the same bad direction. Regrettably, the perils of the pending bill’s approach to patent reform continue, as studied in our next installment.