- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

The north korean nuclear crisis entered a new phase when Pyongyang detonated a nuclear device on October 9, 2006. The response of the international community to the North Korean test was swift and stern. The five other countries participating in the North Korean Six-Party talks condemned North Korea immediately after the test, and the un Security Council passed a resolution imposing new sanctions on the North five days later.

International reactions grew more diverse over time, however. The North Korean nuclear test added new urgency to a peaceful settlement of the crisis and spurred a flurry of diplomatic activity aimed at solving it through the Six-Party talks. Some would argue that this greater interest in diplomacy was responsible for the February 2007 accord in Beijing on the initial steps toward North Korea’s nuclear disarmament.

But whether or not the nuclear test will change the basic configuration of national interests and policies on the North Korea security threat remains to be seen. Even in the aftermath of the provocation, three members of the Six- Party talks, South Korea, China, and Russia, have expressed clear reservations about drastic change in North Korea policy and emphasized the importance of diplomacy and dialogue in resolving the nuclear crisis. South Korea, in particular, has been reluctant to revise its engagement policy toward the North. Nor do the recent Six-Party talk agreements mean that Washington and Tokyo have given up their hard-line policies toward Pyongyang. Distrust of the North Koreans runs deep in Washington, and American negotiators went out of their way during the February 2007 talks to emphasize the tentative nature of the Beijing agreement.

In particular, the disagreement between South Korea and the United States is likely to persist even as they work together for the successful completion of the Six-Party talks. The current discord between the two allies goes back to the early 2000s, when the new Bush administration adopted a hard-line approach toward the North, and Seoul chose to adhere to the policy of engagement with Pyongyang that began in 1997 with the election of Kim Dae Jung as president. When Roh Moo-hyun succeeded Kim in 2002 and continued with the pro-engagement approach, it became apparent that South Korean assertiveness was here to stay.

Given the importance of the engagement policy to the identity and legacy of the current South Korean government, it is highly unlikely that it will be aggressive in supporting the un sanctions and other U.S.-led hard-line initiatives. If the past nine years of South Korean policy are any indication, it will likely take a change of government in Seoul to see a fundamental transformation in South Korea’s policy toward the North. No wonder that the upcoming presidential election in December 2007 is attracting so much attention.1

Many believe that if the conservative Grand National Party (gnp) wins after a decade in opposition, it will return to the pre-1997 hard-line policy. Likewise, it is said that another victory by the ruling Uri party will lead to the continuation of the pro-engagement policy. But I argue that these expectations are merely assumptions. There is no guarantee that a new gnp government will adopt a stand that is drastically different from that of the current administration. Neither can we assume that the next Uri government will automatically inherit Roh’s security policy. Rather, it seems more likely that the next government’s security policy will be determined not only by the party that captures power, but also by the nature of the factions that gain control of party policies.

In my view, there are at least four schools of thought that may determine the security policy of the next government. This essay will first explore the differences and commonalities among the four schools, before discussing which school is more likely to ensure long-term security for the country. I will then examine the political approaches that proponents will have to undertake in order to shape South Korea’s post-Roh security policy.

Left and right

Since Kim Dae Jung became president in 1997 and adopted the policy of engagement toward Pyongyang known as the sunshine policy, the left and the right have repeatedly clashed over issues ranging from North Korea’s nuclear policy to the U.S.-Korean military alliance and regional security. 2 In South Korean politics, the left is represented by the past two governments of Kim Dae Jung and Roh Moo-hyun, while the right by the opposition Grand National Party. Although the left-right distinction is useful for describing the main cleavage in the South Korean foreign policy establishment, it obscures significant differences among various factions within each group. Therefore, new terms are needed in identifying major security orientations.

We can start differentiating groups by identifying key policy issues. The two main issues that divide policymakers and experts in South Korea are first, how best to exercise power toward the North, and second, where, between South Korea and the United States, to place responsibility for dealing with North Korea.

On exercising power toward the North, there are two positions — engagement and coercion. Those who want to engage North Korea are liberal because they believe that North Koreans are not inherently aggressive and that sustained engagement can modify Pyongyang’s behavior. Opponents of the engagement approach, doubtful that Pyongyang would be satisfied with the benefits of cooperation, present a classically realist argument. They believe that North Koreans are belligerent and that such hostility can only be deterred by the full display of power involving both rewards and punishments. Certainly, this debate between liberals and realists over how to view North Korea is hardly unique to South Korea. The debate is also a contentious one within the United States between doves and hawks. But the South Korean division on the second issue — which country should be responsible for exercising diplomatic leadership toward North Korea — is less universalistic and has largely been shaped by the country’s history.

Pan-Korean nationalists believe that Seoul should assume primary responsibility. Another group, known as the pro-Americans, believes that the responsibility should fall squarely on the shoulders of Washington, given the U.S.-South Korean military alliance. The pro-Americans have no qualms about South Korea’s taking a backseat when it comes to negotiating with or defending the South against the threat from the North. Yet another group, the multilateralists, takes a more nuanced position. While recognizing the importance of the U.S.-South Korea alliance, their emphasis is on maintaining an equal relationship. They are also more open to the idea of allowing China and other countries to participate in the diplomatic process to resolve the North Korean issue.

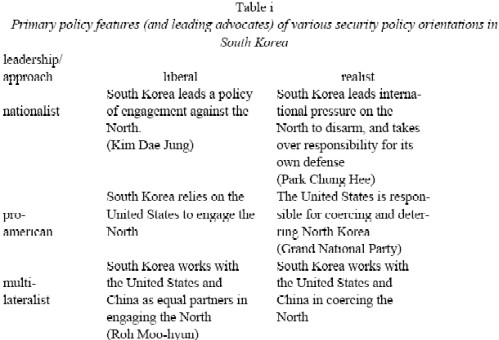

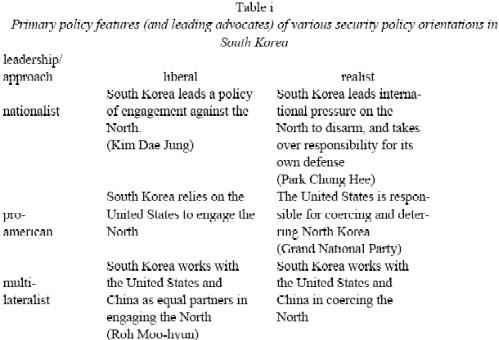

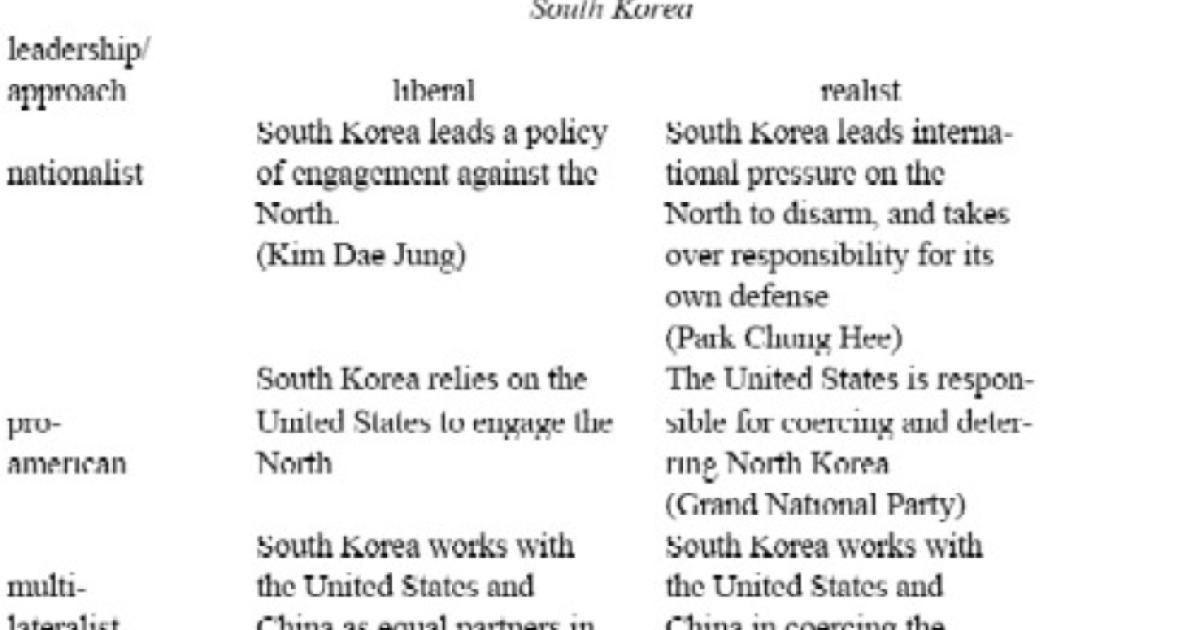

So, depending on one’s position on the two issues, there can be six possible perspectives on South Korean security policy (see Table i). Among them, I have identified liberal nationalism, liberal multilateralism, realist nationalism, and realist pro-Americanism as the four leading contenders.3

Table I

Primary policy features (and leading advocates) of various security policy orientations in South Korea

| leadership/ approach |

liberal |

realist |

Nationalist |

South Korea leads a policy of engagement against the North. (Kim Dae Jung) |

South Korea leads international pressure on the North to disarm, and takes over responsibility for its own defense (Park Chung Hee) |

Pro-American |

South Korea relies on the United States to engage the North | The United States is responsible for coercing and deterring North Korea (Grand National Party) |

Multi-Lateralist |

South Korea works with the United States and China as equal partners in engaging the North (Roh Moo-hyun) |

South Korea works with the United States and China in coercing the North |

1Nicholas Eberstadt analyzed the importance of the 2002 presidential election in the context of the U.S.-Korean alliance. As he predicted, the alliance could not withstand the leftist shift of Korean politics. Nicholas Eberstadt, “Our Other Korean Problem,” National Interest 69 (Fall 2002).

2For a comprehensive analysis of South Korean politics based on the left-right dichotomy, see Chaibong Hahm, “The Two South Koreas: A House Divided,” Washington Quarterly 28:3 (Summer 2005).

3We can discern a variant of liberal pro-Americanism among some supporters of Roh Moo-hyun. Bae Ki-chan, who is a foreign policy advisor to Roh at the Blue House, argues that South Korea should enlist the United States as its partner for the reconciliation and reunification with the North. But he does not explain why the United States would go along with this South Korean design. Realistically, it is difficult to imagine that the United States will go out of its way to lead the engagement process that the South Korean liberals favor. Realist multilateralism is not realistic at the moment, since it would require strong security and military cooperation among South Korea, the United States, and China in tackling the North. Bae Ki-chan, Korea Standing Again on a Crossroads of Survival (Wisdom House, 2005).

4 South Korean geographical proximity to the North would always make Seoul more risk-averse than Washington in using coercion.

5South Korean conservatives have long feared that Roh will turn to the summit meeting with Kim Jong-Il in an attempt to revive the chances of the ruling Uri party in the 2007 election. From this perspective, the pursuit of a second summit by Roh would be purely a domestic political act, not a change in his policy preferences.

6Chung-in Moon, “Confidence-Building and Peace-Building in Asia,” paper presented at the East Asia Research Forum, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea (September 23–25, 2005).

7See Bruce Klingner, “South Korea’s Growing Isolation,” Asia Times (August 5, 2006). .

8Realist nationalism was the dominant ideology of the South Korean government during the Cold War. Former president Park Chung Hee was a classic realist nationalist. Even under the structure of the U.S.-Korean security alliance, he worked assiduously to develop self-defense capabilities for his military. The fabled Heavy and Chemical Industries Drive of the 1970s, in which Korea’s current industries were initiated, was as much motivated by security imperatives as by economic ones, as it was felt that a strong heavy industry was necessary for an indigenous arms industry. When realist nationalists held power, South Korea kept up its defense spending.

9Yong-sup Han, “Analyzing South Korea’s Defense Reform 2020,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 18 (2006).

10Selig S. Harrison,. “South Korea-U.S. Alliance Under the Roh Government,” Policy Forum Online 2006, 06–28a, Nautilus Institute. See also Doug Bandow, “Seoul Searching: Ending the U.S.-Korean Alliance,” National Interest 81 (Fall 2005).