- Energy & Environment

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- US

- Contemporary

- Military

- World

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- History

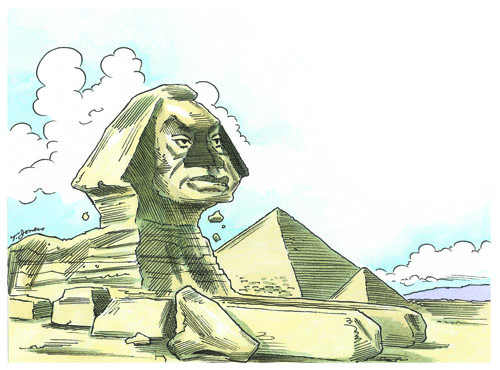

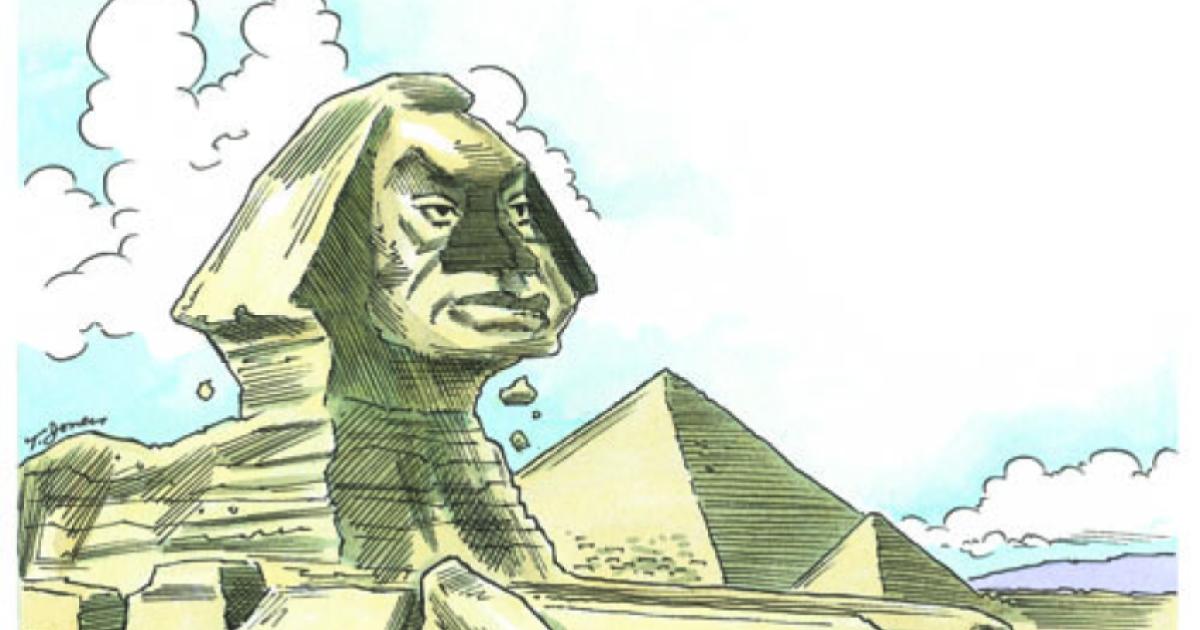

Why do certain dictators survive while others fall? Throughout history, downtrodden people have tried to throw off the yoke of their oppressors, but revolutions, like those now sweeping the Arab world, are rare.

Despotic rulers stay in power by rewarding a small group of loyal supporters, often composed of key military officers, senior civil servants, and family members or clansmen. A central responsibility of these loyalists is to suppress opposition to the regime. But they carry out this messy, unpleasant task only if they are well rewarded. Autocrats therefore need to ensure a continuing flow of benefits to their cronies.

If the dictator’s backers refuse to suppress mass uprisings or if they defect to a rival, then he is in trouble. That is why successful autocrats reward their cronies first and the people last. As long as their cronies are assured of reliable access to lavish benefits, protest will be severely suppressed. Once the masses suspect that crony loyalty is faltering, there is an opportunity for successful revolt.

Three types of rulers are especially susceptible to desertion by their backers: new, decrepit, and bankrupt leaders.

Newly ensconced dictators do not know where the money is or whose loyalty they can buy cheaply and effectively. Thus, during transitions, revolutionary entrepreneurs can seize the moment to topple a shaky new regime.

Even greater danger lurks for the aging autocrat whose cronies can no longer count on him to deliver the privileges and payments that ensure their support. They know he can’t pay them from beyond the grave. Decrepitude slackens loyalty, raising the prospects that security forces will sit on their hands rather than stop an uprising, giving the masses a genuine chance to revolt. This is what brought about the end of dictatorships in the Philippines, the former Zaire, and Iran.

Earlier this year, in addition to rumors about the health concerns of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, those countries suffered serious economic problems that kindled rebellion. Grain and fuel prices were on the rise; unemployment, particularly among the educated, was high; and in Egypt’s case, there had been a substantial decline in American aid (later reinstated by President Obama). Mubarak’s military backers, beneficiaries of that aid, worried that he was no longer a reliable source of revenue.

As money becomes scarce, leaders can’t pay their cronies, leaving no one to stop the people if they rebel. This is precisely what happened during the Russian and French revolutions and the collapse of communist rule in Eastern Europe—and why we predicted Mubarak’s fall in a presentation to investors in May 2010.

Today’s threat to Bashar Assad’s rule in Syria can be seen in much the same light. With a projected 2011 deficit of approximately 7 percent of gross domestic product, declining oil revenue, and high unemployment among the young, Assad faces the perfect conditions for revolution. He may be cracking heads today, but we are confident that either he will eventually enact modest reforms or someone will step into his shoes and do so.

Contagion also plays an important part in revolutionary times. As people learn that leaders in nearby states can’t buy loyalty, they sense that they, too, may have an opportunity. But it does not automatically lead to copycat revolutions. In many nations, particularly the oil-rich gulf states, either there has been no protest or protest has been met with violence. In Bahrain, for example, 60 percent of government revenue comes from the oil and gas sector; its leaders have therefore faced few risks in responding to protests with violent oppression.

This is because resource-rich autocrats have a reliable revenue stream available for rewarding cronies—and repression does not jeopardize this flow of cash. Natural-resource wealth explains why the octogenarian Robert Mugabe shows no sign of stepping down in Zimbabwe and the oil-rich Muammar Gadhafi gave no hint of compromise when rebellion struck in Libya. Amid NATO bombs falling on Tripoli, however, Gadhafi discovered the need to convince remaining loyalists of his ability to re-establish control over Libya’s oil riches. Otherwise they, too, would have turned on him. Sadly, the victorious Libyan rebels are also likely to suppress freedom to ensure their control over oil wealth.

Regimes rich in natural resources or flush with foreign aid can readily suppress freedom of speech, a free press, and most important, the right to assemble. By contrast, resource-poor leaders can’t easily restrict popular mobilization without also making productive work so difficult that they cut off the tax revenues they need to buy loyalty.

Such leaders find themselves between a rock and a hard place, and would be wise to liberalize pre-emptively. This is why we expect countries like Morocco and Syria to reform over the next few years even if their initial response to protest is repression. The same incentive for democratization exists in many countries that lack a natural reservoir of riches, like China and Jordan—a bad omen for authoritarian rulers and good news for the world’s oppressed.