- State & Local

- California

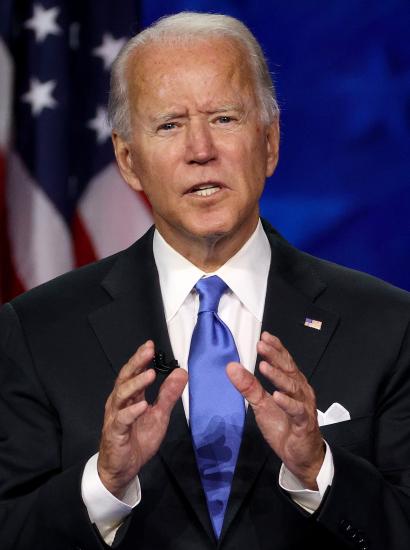

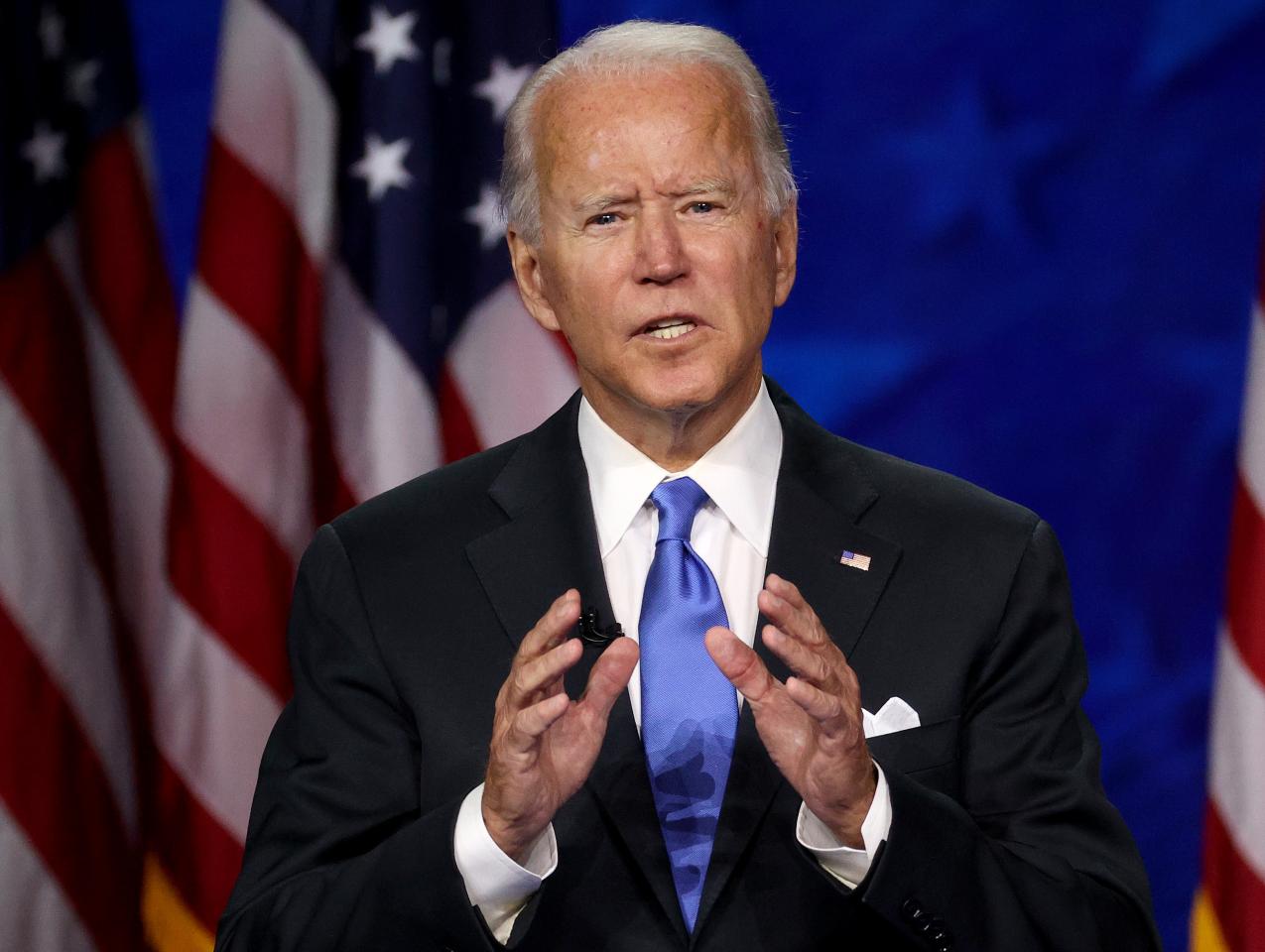

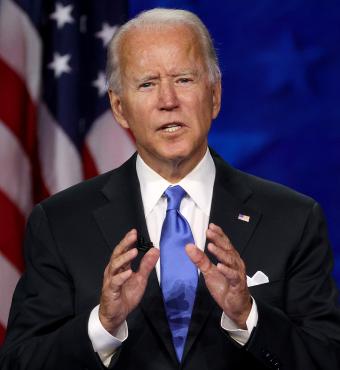

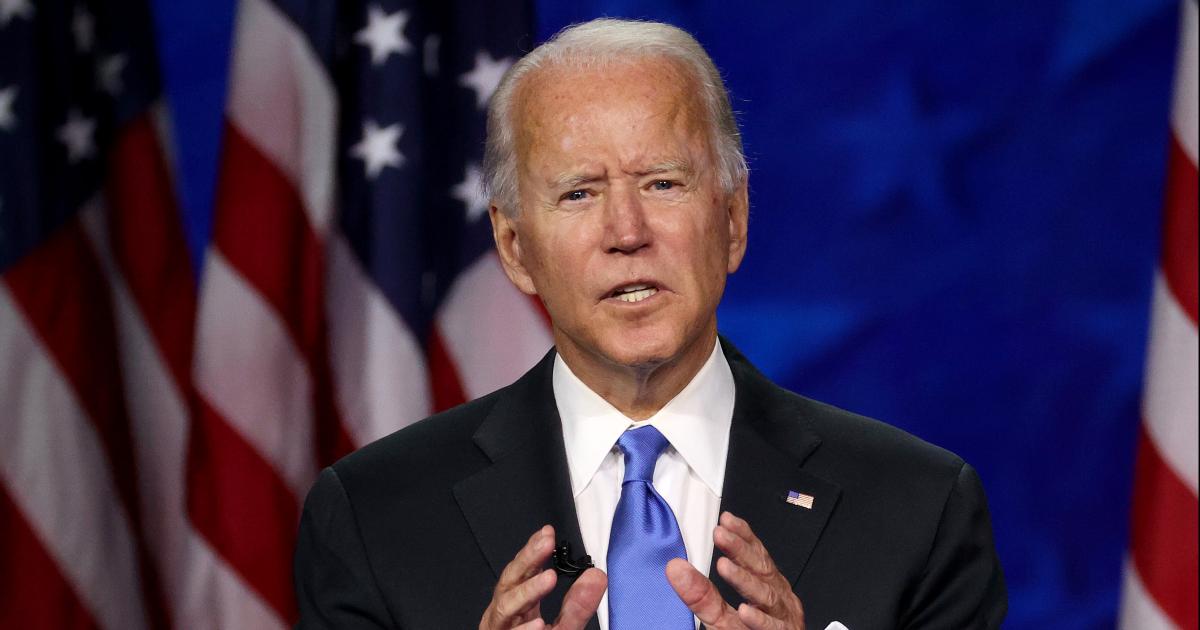

As the White House communications team sheds staffers at an alarming rate (two-thirds of the White House press shop has departed since President Biden took office in January 2021), it’s apparent this administration is off its optics game.

Case in point: the president’s visit, late last week, to the battleship Iowa, now a museum permanently moored in San Pedro, the gateway port to Los Angeles and home of the nation’s largest container-ship operation.

Some staffer(s) decided it would it be a swell idea to use the warship —a symbol of pride and strength, back when dreadnoughts projected national might—as a backdrop while the president talked up all he’s done to help ease the nation’s supply-chain crisis.

A less genteel way of rephrasing that: battleships are a relic of a bygone era—not unlike a president who’s a longtime presence in the nation’s capital yet so far has failed to deliver on his promise of comity and a partisan détente (in case you’re curious, the Iowa was launched on August 27, 1942, some 85 days before Joseph Robinette Jr. entered the world).

Here’s yet another way to look at Biden’s visit to Southern California, his first journey to the Golden State since last September, amid the failed recall attempt against governor Gavin Newsom: it’s a different Democrat in the Oval Office—one with a different approach to the nation’s most populous and one of its bluest states.

Biden has now traveled to California twice during his presidency. By the time of their first midterm elections, respectively (in 1994 and 2010), fellow Democrats Bill Clinton and Barack Obama had dropped by the Golden State 14 and 7 times.

In Biden’s defense, one could attribute Biden’s California “neglect,” as it were, to the Golden State’s lack of interparty competition and the Democrats’ uncontested status in presidential elections (by contrast, Biden has visited swing-state Pennsylvania nine times already).

When Bill Clinton captured the presidency in November 1992, he did so with the help of California’s then 54 electoral votes (not a difference maker, as Clinton earned 370 election votes in the election, 100 more than necessary).

But Clinton’s California victory was an anomaly in at least two regards. First, he benefited from the late H. Ross Perot’s taking 20.6% of the November vote (Clinton received 46% to then president George H. W. Bush’s 32.6%). Second, it marked the end of Republican dominance of California in national races, the GOP nominee having carried the Golden State in nine of 10 previous presidential votes dating back to 1948.

Clinton’s approach to California: visit often to keep it in the blue column (in Clinton’s second term, California took on a personal importance after his daughter enrolled at Stanford University).

By the time of Barack Obama’s first presidential visit to California (a medley of talking up electric vehicles and his stimulus package, coupled with a Tonight Show appearance), election outcomes no longer were in doubt in the Golden State, not with Obama carrying 61.1% of the November 2008 vote.

The Obama approach: maintenance of the Democratic base, plus care and feeding of donors. Translation: Obama presidential visits were a blend of official business (so that the government would pick up the tab for the use of Air Force Once) and a lot of fundraising.

Yes, President Biden could treat California the same as his former running mate did (indeed, he did two fundraisers in the Los Angeles area the same day as his port event). However, the same atmospheric conditions that worked for his predecessor don’t apply.

The early phase of the Obama presidency was marked by enthusiasm and the great novelty of the nation’s first Black president. Biden is anything but a novel figure, having first arrived in Washington just seven months after the infamous Watergate break-in (this week being the 50th anniversary of the “third-rate burglary”). Moreover, Biden’s limited media appearances are defensive in nature—compare the aforementioned Obama interview with Jay Leno to Biden’s last week, taking softball questions from Jimmy Kimmel (featuring not much optimism, but a whole lot of blame directed at Vladimir Putin, oil companies, and Republicans).

Will Biden return to California in the near future? It is an election year, so it’s safe to assume that there will be more fundraisers between now and November (if you’re a political junkie, keep an eye on presidential travel to California-adjacent Arizona and Nevada, where two incumbent Democratic senators are in tight races).

My question: if the president’s real purpose for coming to California is to raise campaign money, what’s the nonpolitical policy that justifies said trips as “official business”?

Here, both California and the president’s own actions do him no favors. Like Obama back in 2009, Biden could do an event centered around electric cars. But reporters would tie that appearance to the White House’s very public feud with Elon Musk. Besides, any talk about electricity raises the question of whether California will have an ample supply this summer—and to what extent that’s the result of an overreliance upon renewable energy (hydropower in particular), an unwillingness to split atoms, plus the irony of state officials needing fossil fuels more than they’d care to admit.

What else could Biden do in California?

There’s always his professed love of trains and the promise of showering states with billions of federal infrastructure dollars. Indeed, last summer, the Biden administration restored almost $1 billion in federal grant money withheld by the Trump administration for California’s beleaguered high-speed rail project. However, Biden would have to explain why the last federal infrastructure bonanza contained no earmarks for high-speed rail projects.

Fine, then, but what about the least controversial Biden event of all—his frequent outings for ice cream cones? Welcome to the issue of inflation, perhaps paramount on voters’ minds this fall. With inflation taking a toll on food prices (including dairy), the cost of a presidential cone is almost 10% more than it was a year ago (inflation and supply-chain issues also negatively impacting ice cream and froyo manufacturers and vendors).

None of this is to suggest that California is an island upon which President Biden would find himself alone. At last week’s port event, the president was surrounded by the following Democratic entourage: US senator Alex Padilla; Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti; Long Beach mayor Robert Garcia; congressional representatives Alan Lowenthal, Nanette Barragan, and John Garamendi; Los Angeles County supervisor Janice Hahn; and Los Angeles city councilman Joe Buscaino. In all, pretty good for a “public” event that wasn’t advertised or open to the general public.

So, no, the problem isn’t that President Biden lacks for California friends. Rather, it’s that California doesn’t offer many policy showcases during a year in which the president’s party sorely needs to link progressivism to progress.

Moreover, the irrational exuberance of some leading California officials is out of step with a grim electorate. One such example: this tweet by governor Newsom on the night of his primary win: “Across the country, Republicans are attacking our fundamental rights as Americans. Destroying democracy, stripping a woman of the right to choose, and standing idly by as gun violence claims far too many lives. . . . CA is the antidote—leading with compassion, common-sense and science. Treasuring diversity, defending democracy, and protecting our planet. Here's to continuing that fight.”

Maybe President Biden will keep coming west to engage in that “fight.” But that’s a long way to travel just to get into a brawl—and a departure from previous Democratic presidents who approached the Golden State as lovers, not fighters.