- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- California

Politics is not unlike poker in this one regard: candidates and incumbents often have “tells”—tics, mannerisms, or ways of saying things that indicate the strength of the hands they’re holding.

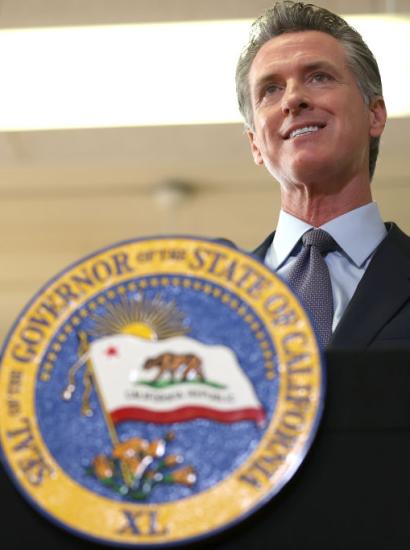

A case in point: California governor Gavin Newsom, whose tell is the repeated use the phrase “Period. Full stop” to say a matter’s settled when, in fact, it’s not.

Newsom used those very words in January to describe the outcome of Proposition 1, a $6.38 billion bond for mental health facilities and the lone ballot measure in California’s March statewide primary. “I think it’s going to win overwhelmingly. Period. Full stop,” Newsom told a Los Angeles Times reporter in January. Last week, Newsom reportedly was scrambling to correct rejected ballots as Proposition 1 clung to a lead of 20,000 votes, reflecting 50.1% of the statewide tally.

I’ve done several internet sweeps to see where else Newsom has used the phrase. “Period. Full stop” was used in the governor’s denial of any conflict of interest between his policy decisions and his wife’s cinematic efforts; his insistence that funds for California road repair can’t be repurposed; and his outrage in claiming retail-store theft is unacceptable.

But the one area where I couldn’t find the Newsom tell: the times when he’s said he has no intention of a presidential run in 2024.

And maybe that’s because Newsom understands that were he to have challenged President Biden this year, no amount of bluffing could have disguised the governor playing a weak political hand.

Here’s why:

Let’s begin with some presidential history and the last two times a Democratic president has faced a significant primary challenge (one involving a California governor).

In 1968, the Democratic order crumbled in less than 20 days. On March 12 of that year, Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy collected 42% of the New Hampshire presidential primary vote; in the same contest, president Lyndon Johnson was unable to crack 50%. Four days later, New York senator Robert F. Kennedy entered the race. Two weeks later, Johnson told a stunned nation that he wouldn’t seek reelection.

Although Newsom has long maintained that RFK is his political idol, the 2024 election (so far) hasn’t offered a “blood in the water” moment akin to those three weeks in March 1968, when an opportunistic Democrat could jump into the race—and, in doing so, send the embattled incumbent into retirement. Other than a setback in American Samoa, Biden’s performance “floor” in the 2024 primaries is a 63.9% win in New Hampshire. While a chronic “uncommitted” primary vote suggests problems for Biden moving forward with a disenchanted progressive base, it didn’t encourage any prominent Democrats to enter the primary field.

That leaves Newsom with 1980 as a model for a presidential run.

And here, the 2024 version of that scenario unravels very fast.

In 1980, as in 1968, president Jimmy Carter faced not one but two significant Democratic challengers: the late Massachusetts senator Edward Kennedy; and California governor Jerry Brown, in the final two years of his first eight-year stint as California’s chief executive.

Brown’s run would run out of gas in the 1980 Wisconsin primary, where he poured time and treasure into the state only to walk away with an anemic 12% of the Democratic vote (to 56% for Carter and 30% for Kennedy).

But Brown’s run wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment springtime decision. Instead, he announced his challenge to Carter in November 1979, a day after Kennedy had announced his run, presenting himself as an ambassador of change. “I see the problem not so much as the deficiency of one personality,” Brown told his announcement gathering, “but rather as the collective failure to grasp the new age into which we are entering.”

Brown, in that campaign kickoff, listed a series of policy breaks with the incumbent president: a proposed constitutional amendment requiring a balanced budget, a limit on military spending, a phasing out of nuclear power, plus the creation of a federal agency tasked with purchasing all foreign oil for resale to domestic refiners.

And where was Gavin Newsom in November 2023? Not outlining his differences with the Biden administration, but doing the very opposite: after weeks and months of raising his national profile, he told White House aides that he wouldn’t seek the presidency in 2024.

Even had Newsom decided to take the plunge—tempting though it might have been to have offered himself as a generational alterative (Newsom’s nearly 25 years younger than Biden)—there was one other consideration that might have proved fatal: the Democrats’ primary calendar.

First, Newsom and his strategists would have faced tough choices on how to approach the first tier of early primaries and caucuses in January and February—i.e., how to handle time, money, and expectations in the likes of Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Michigan, and Nevada (the latter being the only state in this bunch within proximity of the Golden State).

Perhaps Team Newsom would have decided to wait until the first Tuesday in March and pour the campaign’s resources into Super Tuesday—offering up Newsom as a “native son” candidate in California, plus maybe dabbling in the more regional Colorado and Utah primaries the same day.

The problem with this strategy, especially in California: limited returns.

In this year’s California primary, facing scant opposition, President Biden walked away with 424 delegates (out of the 1,968 needed for nomination). But in past contested presidential primaries in the Golden State, the delegate haul hasn’t been as dramatic. Vermont senator Bernie Sanders won the March 2020 primary by 8 points, receiving 225 delegates to Biden’s 172. In the June 2016 primary, Hillary Clinton bested Sanders by 7 points, receiving 269 delegates to Sanders’s 206. And in California’s February 2008 primary, Clinton topped Barack Obama by 8 points, receiving 204 delegates to Obama’s 166.

Fine, one might say: a strong Newsom performance in California might not have given the governor the wealth of delegates he’d have liked, but it might have sparked a media narrative of a candidate “living to fight another day.”

The problem with that scenario: Where would the Newsom presidential campaign have gone after Super Tuesday? The March 12 slate of Democratic primaries included Georgia, Hawaii, and Washington. This week’s slate included Arizona, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, and Ohio, followed by Louisiana and Ohio this weekend (here’s the complete primary calendar). As none of those states would seem tailor-made to Newsom, one doubts that he would have lasted until April Fool’s Day, which was Brown’s exit point in 1980.

There’s one other example of a California governor seeking the presidency that’s more germane to Gavin Newsom’s current position. But it’s not the case of a Democratic governor challenging an incumbent Democratic president. Rather, it’s Ronald Reagan’s experience in 1968 in trying to secure the Republican presidential nod.

Unlike Newsom in 2024 or Brown in 1980, Reagan was a first-term governor just two years into his job. But like Newsom, Reagan toured the nation on speaking tours while denying he was a presidential contender (Richard Nixon dubbed him “a more active noncandidate”).

Unlike Newsom in 2024, Reagan actually appeared on 1968’s presidential primary ballot in California as a “favorite son” candidate (he still wasn’t an announced candidate when that vote occurred in June). But like Newsom (one might imagine), Reagan relished the thought of a nomination fight at that year’s national convention—the idea being that Reagan and rival contender New York governor Nelson Rockefeller would amass enough delegates to prevent a Nixon win on the first ballot.

In the end, Reagan’s strategy didn’t pan out. While his unopposed win in California and presence in a handful of other GOP primaries meant that Reagan won a plurality of the primary popular vote nationwide, he couldn’t stop Nixon from a first-ballot win (the final delegate tally: Nixon 692, Rockefeller 277, Reagan 182). When Reagan sought the presidency a second time, as a former governor almost two years out of office, he opted for a traditional November announcement just two months before the 1976 Iowa caucuses instead of 1968’s cat-and-mouse approach.

History is rife with what-if’s. For example, in the same year that Reagan hoped to deny a former vice president his party’s nomination, Democrats tried to do the same to a sitting vice president at their national convention in Chicago. The what-if: could Robert Kennedy have been nominated, at the expense of Hubert Humphrey?

Conversely, a theoretical Newsom presidential run in 2024 doesn’t spawn so many what-if’s as it does questions of “when” (when such a candidacy runs out of steam) and “why” (why a governor would think he could topple a sitting president with a primary schedule designed to the incumbent’s advantage).

History hasn’t been kind to California governors with presidential ambitions. Whereas Reagan prevailed (as a former governor), Jerry Brown and Pete Wilson failed—at times, spectacularly.

Again, the Reagan model is the one for Newsom: leave office, then seek the oval one on the other coast.