- Law & Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

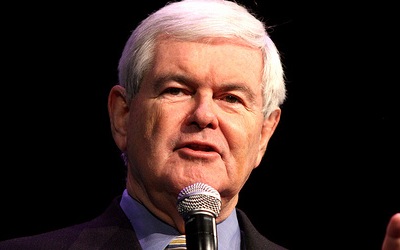

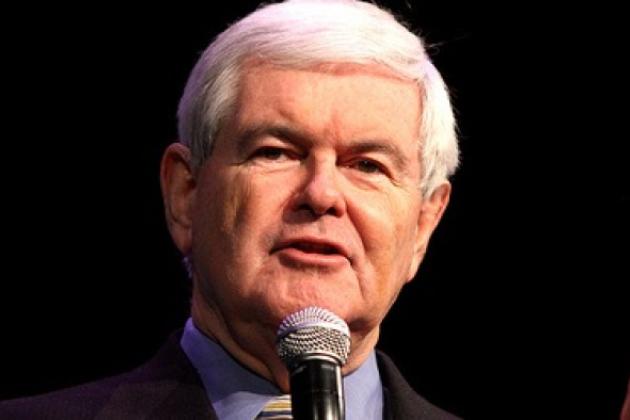

Last month, presidential candidate Newt Gingrich released an agenda of executive and legislative actions to halt the abuse of judicial authority and to restore the constitutional separation of powers. According to the Gingrich plan, the most fundamental values of American constitutionalism are at stake:

A judicial branch that is largely unaccountable and not subject to meaningful checks and balances can—and does—routinely issue constitutional rulings that threaten individual liberties, compromise national security, undermine American culture, and ignore the consent of the governed.

Whether or not he manages to stay in the presidential race, Gingrich has set the stage for a serious discussion of the role of the federal courts. The presidential candidates and the American public should take up the Gingrich challenge.

While there is much of merit in the Gingrich proclamation, unfortunately it frames the issues in the now commonplace dichotomy of judicial activism versus judicial restraint. But a recent Institute for Justice study shows that activism is not the problem. In fact, as I have argued elsewhere, we could use more of the right kind of judicial activism. Judicial reform, founded on the activism/restraint dichotomy evident in the Gingrich plan, actually threatens liberty—the very first of Gingrich’s stated concerns.

Photo credit: IPS Inter Press Service

Judicial activism, in the nature of interference with legislative and executive policy-making, does violate the constitutional separation of powers. But when individual liberties are threatened by the executive and legislative branches, an activist judiciary is essential to protecting individual rights from the tyranny of the majority and from the executive abuse of power. With a better understanding of the dangers posed by both activism and restraint, a revised Gingrich agenda could serve our nation well.

Gingrich suggests three broad approaches the executive and legislative branches can take in restoring the constitutional balance of power. The co-equal branches of government can:

—“explicitly and emphatically reject the theory of judicial supremacy and undertake anew their obligation to assure themselves, separately and independently, of the constitutionality of all laws and judicial decisions,”

—“use their constitutional powers to take meaningful actions to check and balance any judgments rendered by the judicial branch that they believe to be unconstitutional,” and

—“employ an interpretive approach of originalism in assessing the constitutionality of federal laws and judicial decisions.”

Rejecting the Theory of Judicial Supremacy

According to Gingrich, the root of the problem is the theory of judicial supremacy, which he says came into full flower with the Supreme Court’s unanimous 1958 decision in Cooper v. Aaron (holding that states are bound by Supreme Court decisions). In Cooper, the Court asserted, incorrectly, that in Marbury v. Madison Chief Justice John Marshall “declared the basic principle that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution” and that this principle “has ever since been respected by this Court and the Country as a permanent and indispensable feature of our constitutional system.”

It may be that many in the legislative and executive branches now defer to the Supreme Court on questions of constitutionality. For example, when asked in a radio interview if Congress has constitutional authority to mandate the purchase of health insurance, Oregon Congressman Peter DeFazio replied: “Well, um, I'm not a lawyer . . . that's why we have courts. Congress often passes laws that are of dubious or questionable constitutionality.” Such deference to the courts is not what Marshall prescribed in Marbury.

What Marshall did say is that the power of judicial review of the constitutionality of executive and legislative actions arises not from any special knowledge or the talents of judges, but from the constitutional responsibility of the courts to decide cases properly before them. In that limited context, where a dispute involving the executive or legislative branch is before a court having jurisdiction and can only be resolved by interpreting the Constitution, the principle stated in Cooper has to be correct. In that setting, the court must be the final arbiter of constitutional meaning or one of the parties becomes a judge in its own cause, and the rule of law is abandoned to the rule of man. This does not mean, however, nor did the Cooper Court intend to suggest, that the courts therefore have authority to, as Gingrich alleges, “actively seek to modify and create new constitutional law from the bench.”

We need more judicial activism in the pursuit of liberty.

The notion that courts, and particularly the United States Supreme Court, can effectively amend the Constitution through their decisions derives not from the theory of judicial supremacy, but from a particular philosophy of constitutional interpretation—namely the so-called living constitution theory. In a nutshell that idea is that a two hundred-plus year old Constitution must be adapted to changing circumstances through interpretation as well as formal amendment. But that is a theory that can be, and is, embraced by some people in all three branches of government. American history is filled with examples of presidents and members of Congress urging necessity in the face of new challenges when the constitutionality of their actions is questioned—a sort of whatever it takes philosophy of constitutional interpretation.

The reality of governance is that the executive and legislative branches face many more constitutional questions in their day-to-day work than do the courts. Courts consider only those constitutional questions brought to them in the course of litigation, and the federal courts have long held that they have no jurisdiction to offer advisory opinions or expound on questions not germane to a case properly before them. The executive and legislative branches, on the other hand, pursue innumerable initiatives, every one of which must be within their constitutional authority if we are to be true to the rule of law. While much of what Congress and the president do is routine and clearly within their authority, some of what they routinely do has never been subjected to the test of constitutionality.

That the executive and legislative branches often fail to consider whether they have the constitutional authority to do what they do may reflect acceptance of the view that only the courts have authority to expound on the Constitution, but that is a failure of the executive and legislative branches, not a usurpation by the courts. All federal officials take a constitutionally mandated oath to uphold and defend the Constitution. Taking action without confirming its constitutionality violates that oath.

Checking Unconstitutional Actions by the Courts

Gingrich does recognize that the executive and legislative branches have failed to assert their constitutional prerogatives to defend their respective powers against judicial interference. His second broad recommendation for restoring the balance of powers focuses explicitly on executive and legislative actions he believes should be taken.

Only five of the sixteen suggested actions would be available directly to a President Gingrich. He could insist on adherence to the philosophy of originalism (reliance on the intentions of the framers of the Constitution) in executive interpretations of the Constitution, declare limitations on the effect of judicial decisions (a la President Lincoln in relation to the Dred Scott decision), ignore particularly offensive decisions (no examples are offered in the plan), challenge existing precedents in the courts (a common practice in all administrations), and issue statements of disapproval of particular judicial decisions (as the President and Congress did in a 2002 law reaffirming the “under God” language in the Pledge of Allegiance, after a 9th Circuit ruling that the language was unconstitutional).

From this list of proposed executive actions, only ignoring particular decisions is very controversial, if what is meant is that the executive can decline to comply with a court order if the president disagrees with the court’s constitutional interpretation. Perhaps President Truman intended to assert such independent interpretive authority when he proclaimed, after the Supreme Court ruled he had no authority to seize the nation’s steel mills during the Korean War (Youngstsown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer), that he would do it again under the same circumstances. But such chest thumping is more easily done, and with less consequence, when the dispute is concluded as it was in the steel seizure case.

Do we really want to start impeaching judges?

To contemplate the constitutional crisis such executive independence might generate, imagine that President Nixon had refused to turn over the condemnatory tapes on the ground that he disagreed with the Court’s interpretation of the constitutional scope of executive privilege, or that Congress had declined to accept the Supreme Court’s holding in Bush v. Gore on the basis of a majority in Congress holding to a different understanding of the equal protection clause. To avoid chaos, there must be finality, and when a question is properly before the courts, the rule of law and the nature of the judicial function require that it come from the courts.

The remaining recommendations for legislative action range from the sublime, if extreme, to the ridiculous. On the ridiculous end of the spectrum is the suggestion that executive and congressional actions will somehow lead the nation’s law schools to better educating their students in the superiority of originalism and judicial restraint. Although he is correct to suggest a significantly leftward tilt among most American law faculties, it is obvious the former Speaker has little experience with law school faculties and their jealous control of the content and philosophy of their courses and curricula. Reforming American legal education may be a bigger challenge than restoring the constitutional separation of powers and, in any event, is surely not within the constitutional job descriptions of the president or Congress.

The Gingrich plan suggests several legislative actions, some of which have been employed in the past (i.e., limiting federal court jurisdiction pursuant to Congress’ power under Article I, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution), and others which have been described as extreme or irresponsible by several commentators and former public officials. Among those thought to be extreme by some are holding judicial accountability hearings (similar to the routine practice with respect to executive officials), refusing to fund the courts, abolition of existing judgeships and courts (the entire 9th Circuit is suggested), and impeachment of judges whose decisions rely on incorrect constitutional interpretations.

Judicial accountability hearings that seek explanations for particular decisions are likely to elicit little beyond the written opinions accompanying most judicial rulings. One of the great strengths of the American judicial process is the routine expectation that judges must explain themselves in writing. In light of that time-honored practice, judicial accountability hearings might be helpful to counter the increasing number of judicial rulings without opinions or with the declaration that the decision will not serve as precedent. But as a general matter, judicial accountability hearings are likely to be very much like judicial nomination hearings—and we know how little of substance we learn from them.

Reduced or curtailed funding of the courts is clearly within the power of Congress, but the consequences could be devastating for individuals whose only remedy for injustice is the courts. Plaintiffs would still have access to state courts, but many of those courts are constantly struggling with funding issues. The reality is that the vast majority of our federal courts’ decisions, including those of the 9th Circuit, are uncontroversial (except to the losing side), and are on matters of day to day importance to the parties involved and to our society and economy. Defunding the courts is a meat axe approach where a scalpel will more effectively restrain judges from making decisions like the relatively few that have raised Speaker Gingrich’s ire.

Abolition of judgeships and particular courts is not unprecedented, but it would be a dangerous invitation for reciprocal creation and abolition of courts when the political tide shifts, as it always does. We have seen ample evidence over recent decades of the influence of politics in the maintenance and staffing of our existing federal court system. Ever since the nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, quid pro quo “borking” has resulted in interminable delay in the filling of judicial vacancies, while filibusters have defeated several well qualified nominees. Even reforms that would be beneficial to the administration of justice, like splitting the 9th Circuit into two circuits of manageable size, fall victim to partisan politics.

Worse, in terms of inviting inappropriate political intervention in the judicial function, is Gingrich’s call for impeachment of judges who “issue unconstitutional decisions or who otherwise ignore the Constitution and the legitimate powers of the two other co-equal branches of the federal government.”

Furthermore, it is probably unconstitutional. The Constitution allows for impeachment for “treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” If deciding a constitutional question wrongly—in the opinion of a majority of House members and two-thirds of the Senate members—constitutes a high crime or misdemeanor, impeachment will become a political threat against all manner of federal officials (including presidents) on the basis of alleged unconstitutional action. While it may be persuasive that purposeful unconstitutional action is a high crime and misdemeanor, can we anymore rely on the president or members of Congress than on federal judges to say what is unconstitutional?

In a speech at Tulane University in 1986 (quoted in an appendix to the Gingrich plan), former Attorney General Ed Meese drew a distinction between the Constitution and constitutional law. His point was that the Constitution is a document of written words while constitutional law is the Supreme Court’s interpretation of those words. It is a useful distinction, but in light of Gingrich’s insistence that all three branches are responsible to independently interpret the Constitution, Meese’s constitutional law category cannot be limited to the Supreme Court’s interpretations.

There is no reason to accept that while the Supreme Court may be in error in its interpretations of the Constitution, the executive and legislative branches will always get it right. Impeachment is an important check on judicial and executive officers, but it would endanger the balance of powers among the three branches of government if Congress could impeach any judge or executive officer on the grounds of its own interpretation of what constitutes unconstitutional action.

Employing the Originalist Method of Interpretation

The Gingrich solution to the foregoing challenge of getting constitutional law to conform to the Constitution is to insist on originalism as the only acceptable method of interpretation. But originalism is not uncontroversial, even among justices Gingrich seems to admire. Justice Scalia, for example, is as suspect of the originalist method as he is of our ability to determine legislative intent, even with respect to legislation enacted by people still living.

Gingrich’s heavy reliance on Thomas Jefferson illustrates the problem. One might fairly ask why Jefferson’s views are relevant to establishing original intent given that he was not a participant in the Constitutional Convention and that he and Spencer Roane of the Virginia Supreme Court lost a lengthy battle against the Federalists (some of whom were at the Philadelphia convention) over the Supreme Court’s authority in relation to the state courts. But even relying on the recorded views of people who were at the convention does not give the originalist a firm grasp on constitutional meaning given that among the 55 delegates and 39 signatories, there were a multitude of intentions, and even more among the hundreds of delegates attending the state ratifying conventions.

Gingrich is right to insist on some form of originalism.

Gingrich is right to insist on some form of originalism, because without the strictures of law established at an earlier time, the rule of law is impossible. If a judge, or a president, or a legislator is free to give the Constitution, or any law, new meaning, we have abandoned the rule of law to the rule of man. Gingrich is also correct to insist that each branch of the federal government has authority to, and cannot avoid, interpreting the Constitution within their respective realms. But as Chief Justice Marshall wrote in Marbury v. Madison: “It is, emphatically, the province and duty of the judicial department, to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule.”

When in the course of resolving the case before it, the Supreme Court must interpret the law of the Constitution, the decisions of that court, in the words of President Lincoln (quoted by Gingrich), “must be binding . . . upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit, while they are also entitled to very high respect and consideration in all parallel cases by other departments of the government.”

As Lincoln also noted, the Supreme Court is not infallible so its decisions must not, in every case, settle the constitutional question immediately and for all time. But the solution is not to impeach judges and eliminate courts, rather it must be to allow the ingenious design of divided government, via both the separation of powers and federalism, to work. To the extent Gingrich is calling on the executive and legislative branches, as well as the states, to assert the authority they believe is constitutionally theirs, he is on exactly the right track. But to the extent he means to dissuade or prevent the courts from performing their constitutional responsibilities, he would put liberty and the Constitution at risk.

The Balance of Powers Is a Means to the End of Liberty

Our concern should not be that abuse of power by the courts intrudes upon the powers of the executive and legislative branches. Rather, our concern should be that an imbalance of powers threatens liberty. The constitutional separation of powers, both horizontally in the national government and vertically in the federal system, forms a structural bulwark against the abuse of government power in general. Confining the courts to their constitutional role is important, but not by Congress and the president asserting independent authority under all circumstances to determine the scope and extent of their own constitutional powers. A President Gingrich could promise an originalist understanding of executive power, and insist that Congress do the same. But candidate Gingrich must know better than any of his competitors that history confirms that both presidents and Congressional majorities will be creative in their interpretations of their own constitutional powers.

Gingrich recognizes that liberty is at risk, but his proposed remedies for judicial overreach take little account of how they will actually impact on individual rights. By taking the position that all judicial activism needs to be restrained, rather than recognizing that an activist judiciary is essential to protecting liberty from the liberty-infringing propensities of the executive and legislative branches, Gingrich would leave Americans exposed to the far more dangerous excesses of executive and majoritarian tyranny.

Gingrich likes both Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as presidential role models But their executive initiatives, as referenced by Gingrich, responded to very different perceived judicial excesses. Lincoln acted in defense of individual liberties in refusing to enforce Dred Scott beyond the parties to the case, and in finally issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. FDR acted in response to Supreme Court decisions defending liberty and limiting the scope of federal power and thus championed Congress’ authority to regulate at the expense of individual liberty.

In defense of his judicial reorganization plan, including the infamous plan to pack the Supreme Court, FDR sounded much like candidate Gingrich: “I want—as all Americans want—an independent judiciary as proposed by the framers of the Constitution.”

Roosevelt continued, “That means a Supreme Court that will enforce the Constitution as written, [and] that will refuse to amend the Constitution by the arbitrary exercise of judicial power.” It seems passing strange, to say the least, that Gingrich, the self-proclaimed candidate of liberty and limited government, would look as a role model to the president who launched the inexorable expansion of the federal government.

Gingrich also quotes James Madison from Federalist No. 51:

Were the power of judging joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the judge would then be the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with all the violence of an oppressor.

Madison was defending the proposal for an independent judiciary. Had he been addressing separation of powers from the perspectives of independent executive or legislative power, Madison might have written something like this: “Were the power of legislating or the executive power joined with the courts, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to the tyranny of the majority or to an oppressor no different than the King.”

Like activist courts, activist presidents and activist legislatures will pursue various and often conflicting ends. The challenge is to both restrain and encourage that activism in the preservation of liberty.