President Donald Trump’s National Security Strategy set a new course by focusing on rebuilding the domestic economy as central to national security and aiming at “rival powers, Russia and China, that seek to challenge American influence, values, and wealth.” Critics observed that the White House seemed to reverse past presidents’ emphasis on advancing democracy and liberal values and elevating American sovereignty over international cooperation.1

Less noticed but perhaps equally revisionist, the Trump administration reversed its predecessor’s course on outer space. Even as American military and civilian networks increased their dependence on satellites, the Obama White House had deferred to European efforts to develop a space “Code of Conduct.” The Trump administration instead relies on unilateralism: “any harmful interference with or an attack upon critical components of our space architecture that directly affects this vital U.S. interest will be met with a deliberate response at a time, place, manner, and domain of our choosing.” On June 18, 2018, President Trump announced a new branch of the military: the United States Space Force.

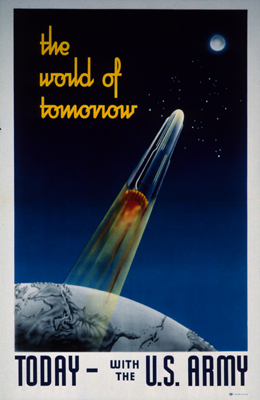

Control of space already underlies the United States’ predominance in nuclear and conventional warfare. Intercontinental and submarine launched ballistic missiles, the heart of the U.S. nuclear deterrent, pass through space to reach their targets. Reconnaissance satellites monitor rival nations for missile launches, strategic deployments, and major troop movements. Communications satellites provide the high-speed data transfer that stitches the U.S. Armed Forces together, from generals issuing commands to pilots controlling drones. With economic rivals such as China and India, and rogue states like Iran and North Korea developing space programs that pursue similar missions, the importance of space technology to U.S. interests and international peace will only increase.

Space not only enhances military operations, but also exposes new vulnerabilities. Anti-satellite missiles can make an opponent’s space-based communication networks easier to disable than purely ground-based systems. Losing reconnaissance satellites could blind the U.S.’s strategic monitoring and disabling the GPS system would degrade its operational and tactical abilities. Space invites asymmetric warfare because anti-satellite attacks could even the technological odds against western powers that have become dependent on information-enhanced operations. As the nation most dependent on space-based networks, the United States may have the most to lose.

Strategists divide competition in this emerging arena into four categories. First is space support, which refers to the launching and management of satellites in orbit. The second is force enhancement, which seeks to improve the effectiveness of terrestrial military operations. The importance of these basic missions is well-established. Indeed, the very first satellites performed a critical surveillance role in the strategic competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. Spy satellites replaced dangerous aerial reconnaissance flights in providing intelligence on rival nuclear missile arsenals. Later space-based systems provided the superpowers with early warnings of ballistic missile launches. These programs bolstered stability and aided progress in nuclear arms reduction talks. Satellites created “national technical means” of verification: the capability to detect compliance with arms control treaties without the need to intrude on territorial sovereignty. They reduced the chances of human miscalculation by increasing the information available to decision makers about the intentions of other nations.

The U.S. has made the most progress in the second mission, force enhancement, by using space to boost conventional military abilities. GPS enables the exact deployment of units, the synchronization of combat maneuvers, clearer identification of friend and foe, and precision targeting. In its recent wars, the U.S. has used satellite information to find the enemy, even to the level of individual leaders, deploy on-station air or ground forces, and fire precision-guided munitions to destroy targets with decreased risk of collateral damage. American military leaders have argued that continued integration of space and conventional strike capabilities will allow the U.S. to handle the twenty-first century threats—terrorism, rogue nations, asymmetric warfare, and regional challengers—more effectively with less resources.

The third and fourth space missions focus on space itself. Space control involves freely using space to one’s benefit while denying access to opponents. Conceptually akin to air superiority, space control begins with defense: hardening command, control, communications and reconnaissance facilities to prevent enemy interference. It includes shielding satellite components, giving them the ability to avoid collisions, disguising their location, and arming satellites to destroy attackers.2

Such forms of active defense can blend into the fourth mission: space force. Space force envisions weapons systems based in orbit that can strike targets on the ground, in the air, or in space. In an important respect, space control and force application demand a greater exercise of power than air or naval superiority. While air and naval superiority can be achieved through rapid deployment of assets for the duration of a conflict, dominance in space requires a broader geographic scope and longer-term duration—a constellation of space weapons would circle the globe for years.3[2]It is in this realm that new weapons technologies are emerging, prompting questions of whether space-faring nations like the United States should treat space as another area for great power competition. “The reality of confrontation in space politics pervades the reality of the ideal of true cooperation and political unity in space, which has never been genuine, and in the near term seems unlikely,” argues Everett Dolman.4 The U.S. certainly has taken such concerns to heart. In the decade ending in 2008, for example, the U.S. increased its space budget from $33.7 billion to $43 billion in constant dollars. The entirety of this spending increase went to the Defense Department.

These weapons systems take several forms. Already operational, the U.S. national missile defense system relies upon satellites to track ballistic missile launches and help guide ground-launched kill vehicles. Space-based lasers, like those in development by the U.S. today, remain the only viable method to destroy ballistic missiles in their initial boost phase, when they are easiest to destroy.

American reliance on space-based intelligence and communication for its startling conventional military advantages has made its satellites a target of potential rivals. In 2007, for example, China tested a ground-launched missile to destroy a weather satellite in low earth orbit—the same region inhabited by commercial satellites. “For countries that can never win a war with the United States by using the methods of tanks and planes, attacking an American space system may be an irresistible and most tempting choice,” Chinese analyst Wang Hucheng has written, in a much-noticed comment.5

Though the 2007 ASAT (Anti-satellite weapon) test sparked international controversy, China had only followed the footsteps of the superpowers. The United States had carried out a primitive anti-satellite weapon test as early as 1959. During the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations, the U.S. continued to test anti-ballistic missile systems in an anti-satellite role. The Soviet Union followed suit. The superpowers temporarily dropped these programs with the signing of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972, only to restart them in the 1990s. As rivals and rogue nations begin to mimic American development of force enhancement and space control abilities, the U.S. will naturally develop anti-satellite weapons to restore its advantage and deter attacks. Such anti-satellite weapons may become even more common due to the vulnerability of satellites and the spread of ballistic missile technology.

Critics question whether the benefits of space weapons are worth the possibility of strategic instability. They argue that only arms control agreements and international institutions can head off a disastrous military race in space. But space will become an arena for pre-emptive deterrence. Every environment—land, air, water, and now space—has become an arena for combat. The U.S. could deter destabilizing space threats from rivals by advancing its defensive capabilities. Some realist strategists argue not just in favor of protecting U.S. space assets, but seeking U.S. space supremacy. Because great power competition has already spread to space, the United States should capitalize on its early lead to control the ultimate high ground, that of outer space.

Criticisms of space weapons overlook the place of force in international politics. Advances in space technology can have greater humanitarian outcomes that outweigh concerns with space weapons themselves. Rather than increase the likelihood of war, space-based systems reduce the probability of destructive conflicts and limit both combatant and civilian casualties. Reconnaissance satellites reduce the chances that war will break out due to misunderstanding of a rival’s deployments or misperception of another nation’s intentions. Space-based communications support the location of targets for smart weapons on the battlefield, which lower harm to combatants and civilians. Space-based weapons may bring unparalleled speed and precision to the strategic use of force that could reduce the need for more harmful, less discriminate conventional weapons that spread greater destruction across a broader area. New weapons might bring war to a timely conclusion or even help nations avoid armed conflict in the first place. We do not argue that one nation’s overwhelming superiority in arms will prevent war from breaking out, though deterrence can have this effect. At the very least, space weapons, like other advanced military technologies, could help nations settle their disputes without resort to wider armed conflict, and hence bolster, rather than undermine, international security.