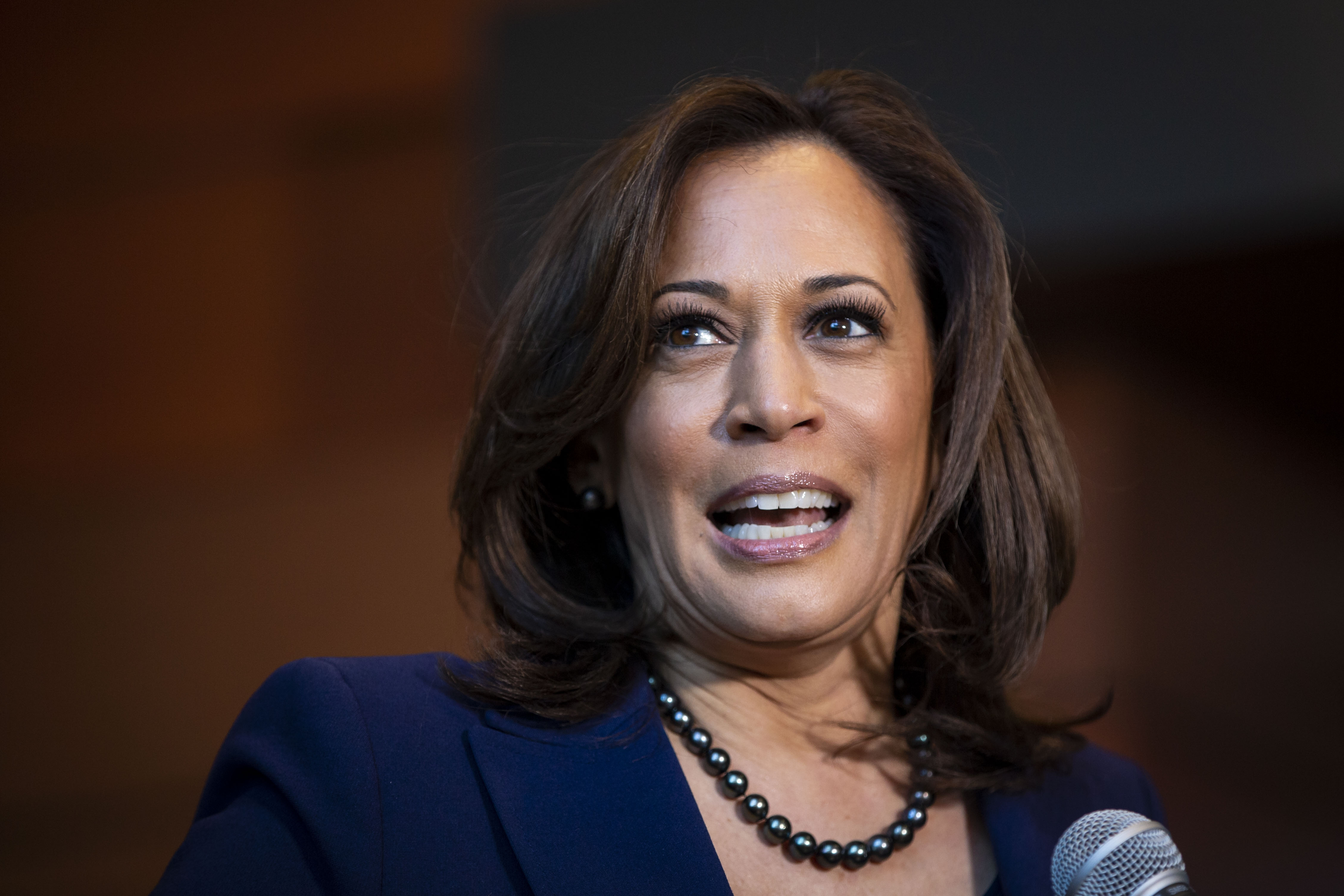

By any reasonable measure, vice president Kamala Harris’s recent visit to Africa —her first visit to that continent as first in line to the presidency—was a success.

The first woman—and woman of color—to serve as vice president of the United States toured a slave fortress in Ghana, met with Africa’s only female president (Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan), and took a swipe at China by calling on that geopolitical rival to go easy on Zambia’s debt burden (China being Zambia’s largest bilateral creditor).

Yet, in the complicated world that represents the political ups and downs of Kamala Harris, the trip had at least two shortcomings.

First, Harris’s trip was overshadowed by a much bigger, breaking story back home—the news of Donald Trump’s indictment and pending arraignment, which made for an awkward press appearance in Zambia.

Second, while Harris’s trip was historical, she was also a victim of history in that her appearance didn’t engender the same enthusiasm as did Barack Obama’s visit to sub-Saharan Africa as president nearly 14 years ago (or so this columnist opines).

Now it’s back to domestic politics, with Harris this week expected to visit a solar power plant in Dalton, Georgia. Such may be the norm between now and November 2024—Harris frequenting the election-pivotal states of Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Wisconsin.

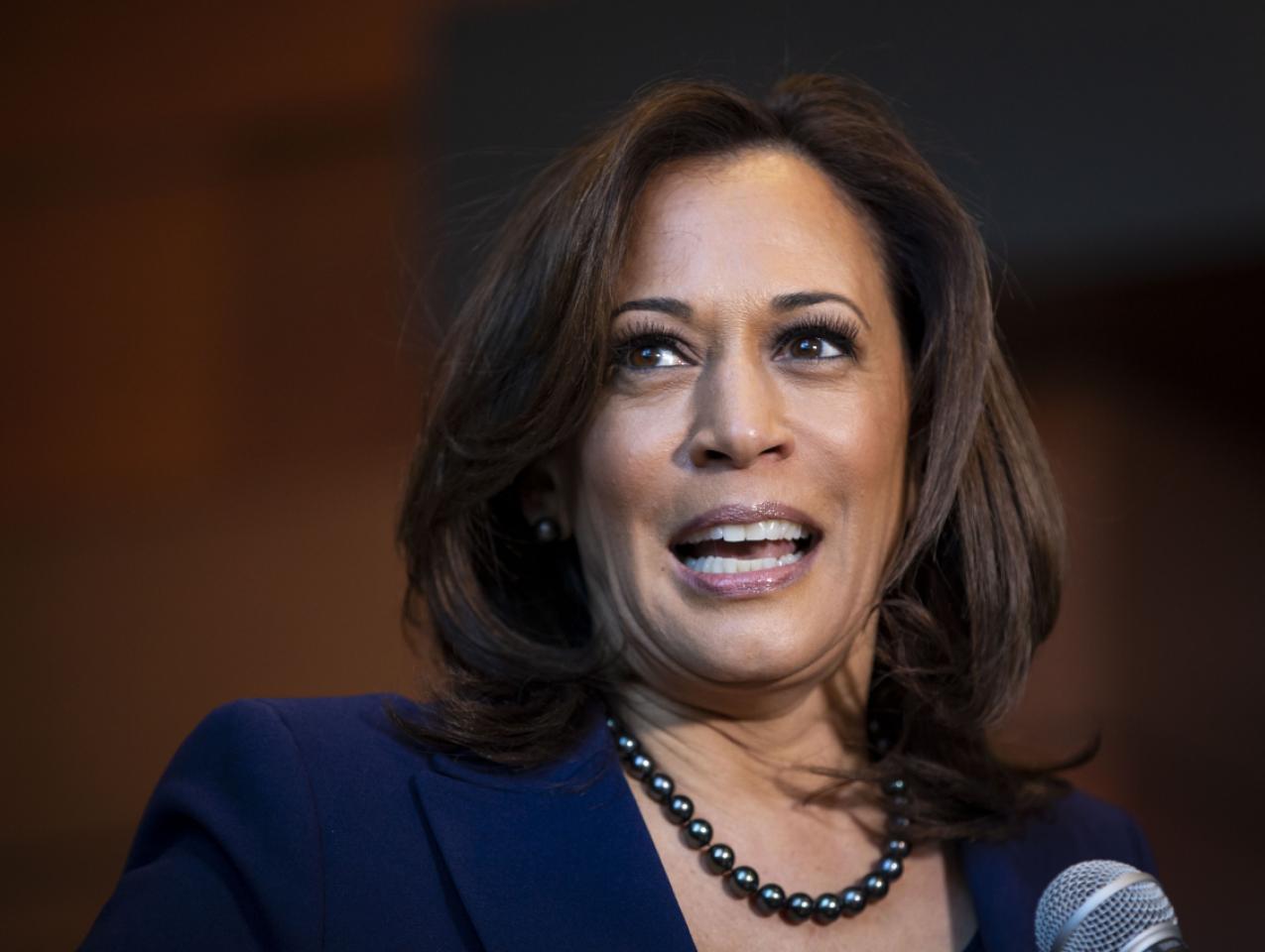

Yet, as she crisscrosses the American landscape, a problem persists: Kamala Harris just isn’t that well liked. The RealClear Politics average of assorted polls has the vice president “underwater”—i.e., her negatives outweighing her positives—to the tune of double digits).

So how did Harris get in this position?

I’ll argue she has herself to blame . . . with some help from the man who gave her this job.

Historically, those vice presidents who’ve thrived in the position have done so by carving out a niche. Al Gore served two terms as Bill Clinton’s sidekick and went on to earn his party’s presidential nomination as incumbent vice president (as did George H. W. Bush in 1988 and Richard Nixon in 1960).

Gore’s approach to the job? “I feel very good about the fact that the president has asked me for advice on the full range of issues he deals with,” Gore asserted in this interview on the eve of the 1996 Democratic National Convention. “And [in] some areas he has asked me to play a more forward-leaning role. Those include the environment, reinventing government, communications and technology policy, empowerment zones in the cities, U.S.-Russian relations, family policy and a few others."

Also considered an exemplar of how to leverage the vice presidency: Dick Cheney. His portfolio (you’ll notice it doesn’t include military strategy and geopolitics): “gatekeeper for Supreme Court nominees, referee of Cabinet turf disputes, arbiter of budget appeals, editor of tax proposals and regulator in chief of water flows in his native West.”

Harris decided not to carve out a niche—at least, nor proactively. Instead, some of her staffers reportedly argued, “she was better off without a formal set of discrete issues and should serve instead as a high-level troubleshooter and advisor in the mode of Walter Mondale (Jimmy Carter’s vice president).”

But then fate stepped in, in the form of president Biden, who made his vice president the lead on the White House’s response to the border crisis, tasking her with making sense of the root cause of increasing migration from Central America. Credit Biden with dealing Harris a bad hand: to the extent his administration had a border policy, it’s “confusing and full of contradictions.”

But also credit Harris with doubling down on that bad hand: rather than confronting the border crisis head-on, she didn’t journey to Texas until three months into her stint as the “border czar”—a role she eventually abandoned. Making matters worse: when pushed by reporters as to what she hoped to accomplish in the way of immigration reform, Harris reverted to a trademark “word salad” (“Let’s recognize with a sense of humanity that these issues must be addressed in a way that is informed by fact and informed by reality and informed by perspective that is dedicated to addressing problems and fixing them in the most constructive and productive way.”)

Add to that salad: a dash of overdefensiveness. Prior to the Texas visit, Harris had this testy exchange with NBC’s Lester Holt:

Holt: “The question that has come up and you heard it here and you’ll hear it again I’m sure, is, Why not visit the border? Why not see what Americans are seeing in this crisis?”

Harris: “We have to deal with what’s happening at the border, there’s no question about that. That’s not a debatable point. But we have to understand that there’s a reason people are arriving at our border and ask what is that reason and then identify the problem so we can fix it.

. . . At some point, you know, we are going to the border. We’ve been to the border. So this whole thing about the border, we’ve been to the border. We’ve been to the border.”

Holt: “You haven’t been to the border.”

Harris: “And I haven’t been to Europe. And I mean, I don’t understand the point you’re making. I don’t discount the importance of the border.”

But critics also point to a second Harris failure: taking the lead (at Biden’s request and her insistence) on the administration’s ill-fated push for federal voting rights legislation.

Where she failed: Harris couldn’t sway two Democratic senators to do the Biden administration’s bidding (maybe she should have channeled yet another former vice president, the arm-twisting Lyndon Johnson). One year into her vice presidency, all Harris had to show for her efforts was not a splashy White House bill signing, but instead this banal statement.

At this point, you might be thinking: the vice president isn’t popular, she has little to show in the way of effectiveness, and her spotty performance continues to worry party insiders, so why not remove her from the 2024 (this assumes that Biden, at some point soon, declares for a second term)?

Don’t count on that scenario ever coming to life—one reason being that the idea of jettisoning the nation’s first woman of color to hold the job doesn’t jibe with a 21st-century Democratic Party that thrives on identity politics.

But also don’t count on any “dump Harris” movement, because history tells us that it’s not easy to manage a coup against a sitting vice president.

Here, Harris can find comfort in the lesson of another Californian who once held her job: Richard Nixon.

In 1956, Nixon was in a position not unlike that of Harris—the junior partner on a presidential ticket with an eye on the Oval Office (Dwight Eisenhower was 22 years older than Nixon, just as nearly 22 years separate Biden and Harris).

And like Harris, Nixon was on uncertain footing as some individuals within the Republican Party wanted him off the ticket. Enter Harold Stassen—aka “Honest Harold,” the chronic presidential candidate—who led a “Dump Nixon” effort at that year’s national convention in San Francisco (yes, there was a time when Republicans would travel to that city).

The question of Nixon’s future hovered over the GOP throughout 1956—Eisenhower not helping his vice president by not putting a kibosh on the speculation. But Stassen couldn’t find the votes at the convention to oust Nixon, and a nationally televised presidential press conference put matters to rest (Stassen later tried to save face by giving a seconding speech for Nixon).

There is no Harold Stassen in today’s Democratic Party—not at this moment, at least. And by that, I mean a prominent figure not only willing to go public with his or her dislike of Harris but willing to start a cabal and put it to a vote at next year’s convention.

Meanwhile, perhaps it’s best for Kamala Harris to fathom that criticism—and rumors of imminent replacement—go with the turf.

Historians have long argued over wither John F. Kennedy would have replaced LBJ on the 1964 Democratic ticket (such a scenario happens in this clever “alternate history” of a second Kennedy term). But we do know that Nixon considering dumping Spiro Agnew in 1972.

Moving forward, there was no “Dump Mondale” effort in 1980 (some Democrats felt he was vital to keeping the party united). Nor did Ronald Reagan consider parting ways with George H. W. Bush, though a pre-1984 small-sample survey of conservatives showed many pining for Jack Kemp as his replacement. As for the 1992 election, Dan Quayle suffered several years’ worth of rumors as to his future—as well as the indignity of the New York Daily News running a 900 number asking readers to weigh in on Quayle’s job security (only 40% of respondents called for Quayle’s ouster).

Speaking of Bush presidencies, George W. Bush’s memoir includes an admission that he considered dumping Cheney in 2004 (his reasoning: “to demonstrate that I was in charge”). Even Biden, as Barack Obama’s ticketmate, had to endure “the firing game”—in 2011, the political rumor mill had it that Hillary Clinton was in line for his job.

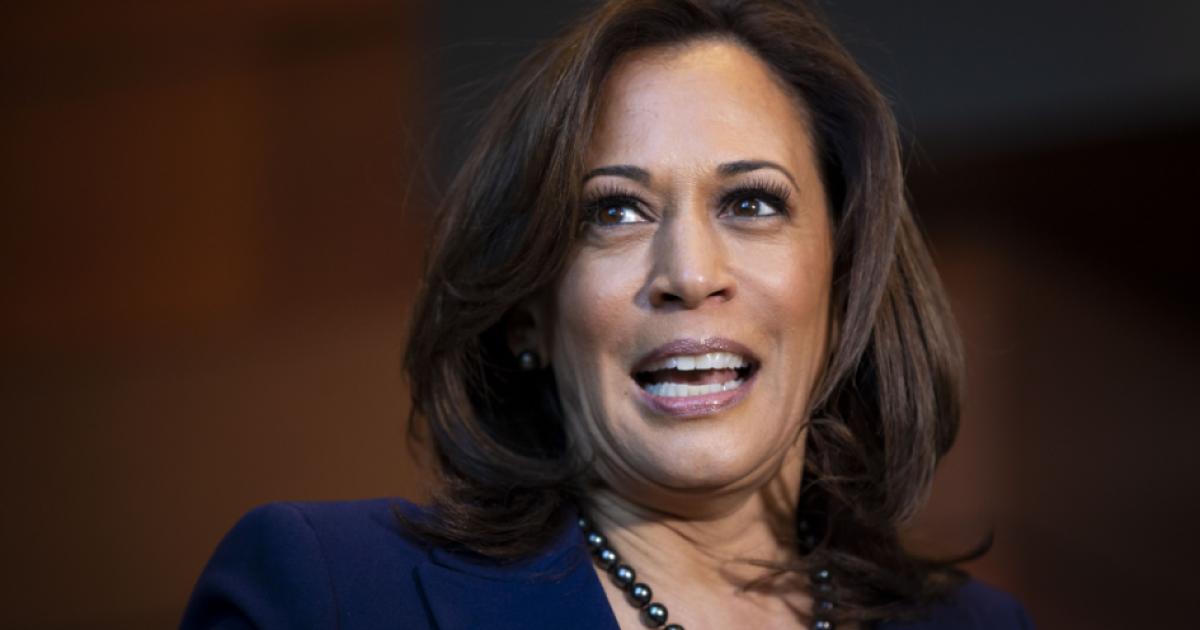

What these lessons from the past 60 years tell us: Kamala Harris isn’t leaving the Democratic ticket in 2024.

And if she ever wants to lead a ticket?

Suffice to say: there’s room for improvement.