- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

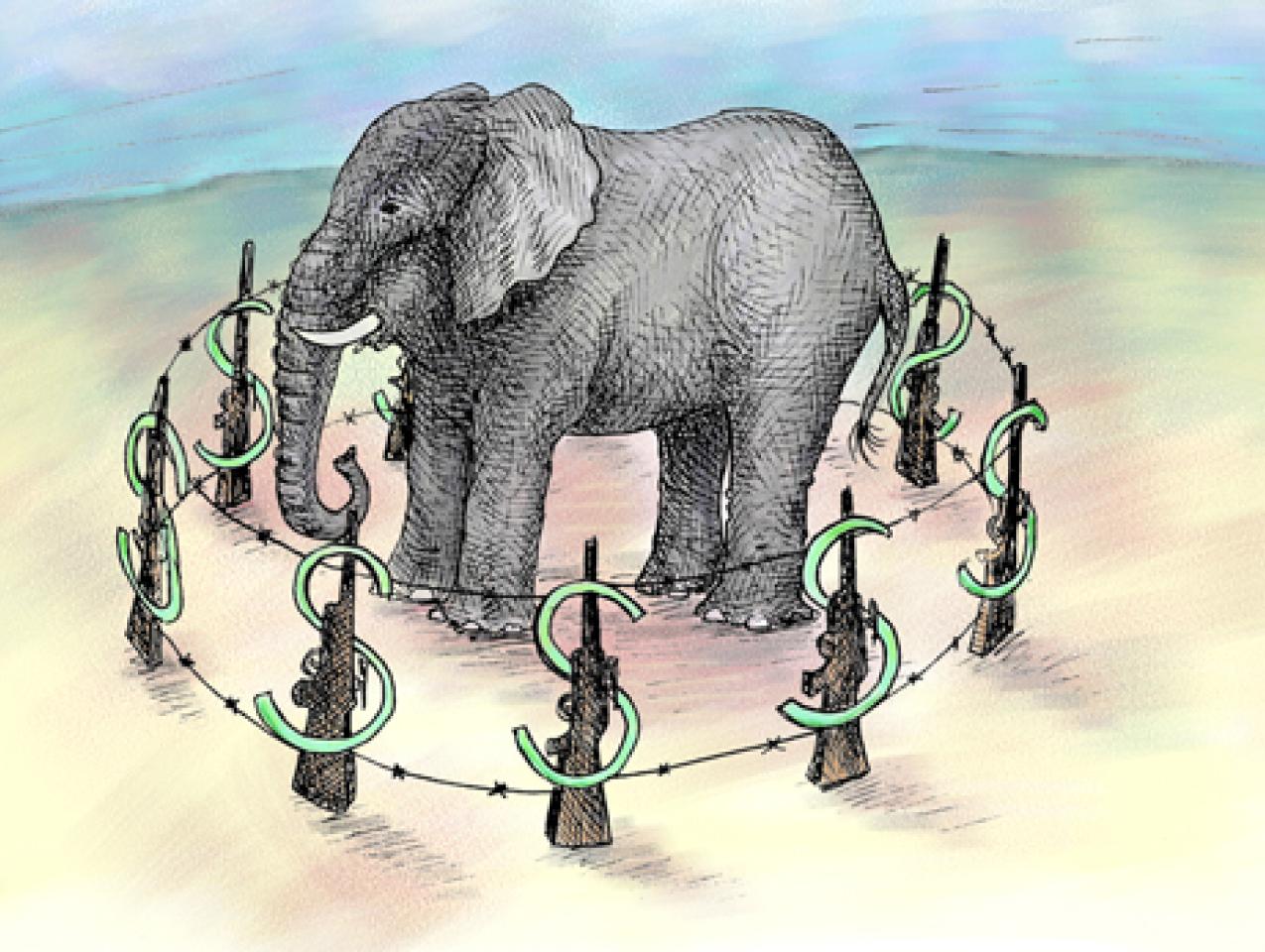

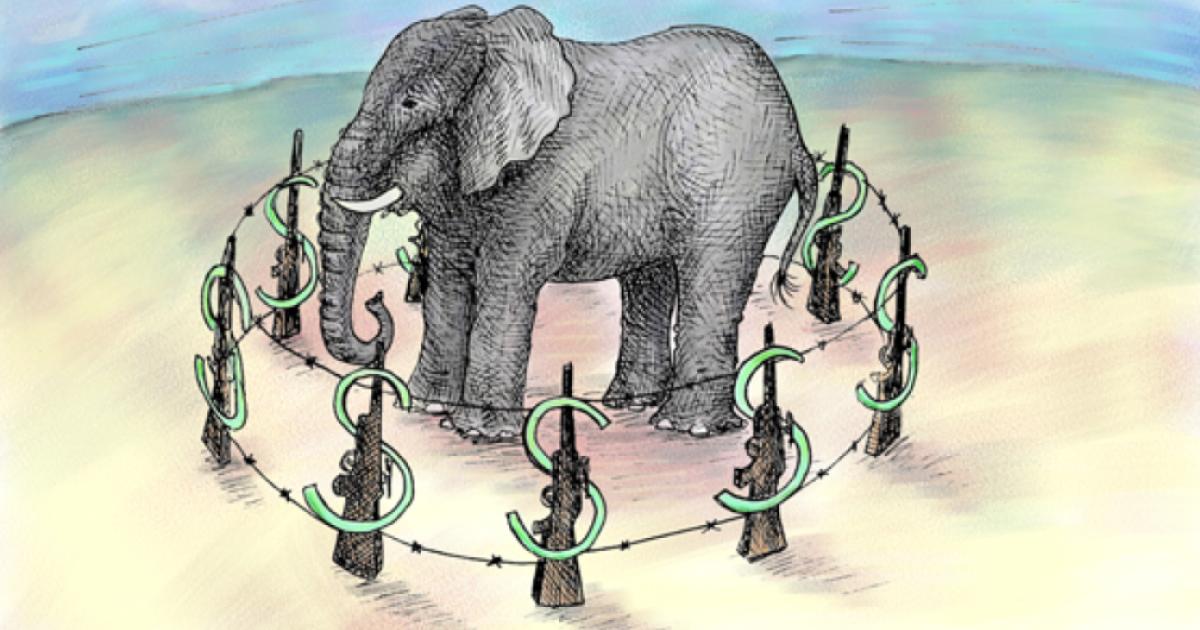

The Department of Interior, which is charged with the enforcement of the Endangered Species Act, has announced its intention to introduce a comprehensive “ban on Commercial Trade of Ivory as Part of Overall Effort to Combat Poaching, Wildlife Trafficking.” That ban will cover both the sale of objects that contain any amount of ivory, however small, and the shipment across state lines by the owner of any object that contains ivory. Unfortunately, the detailed White House Report that outlines a “National Strategy for Combating Wildlife Trafficking” is all too oblivious to vital concerns of private property owners and to the low probability that its draconian measures will reduce the illegal ivory trade.

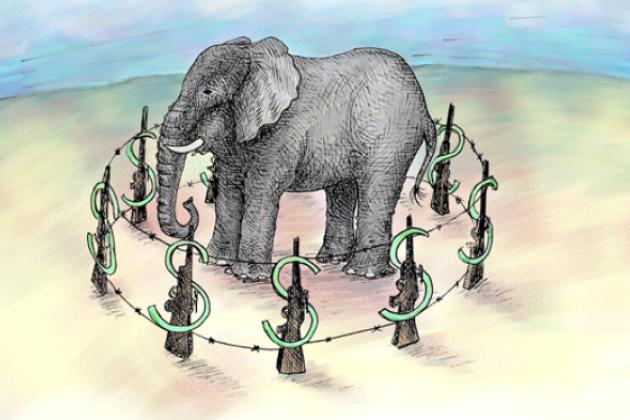

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

To be sure, no one doubts one essential premise of the report; namely, that international trafficking in ivory poses serious threats to the survival of rhinos, elephants, and other animals from the oft-ruthless poachers who kill thousands of animals and then sell their illegal ivory to eager buyers throughout the world, including to many parties in the United States. The illegal trade has also claimed its toll in human lives lost to smugglers who sometimes, as in Kenya, have connections to terrorists.

But the choice of a legitimate end does not address the more difficult question of what means should be used to address the problem. With all guns blazing, the White House report steps up enforcement at all stages of production and distribution, without once mentioning the competing interests of current property owners of ivory: piano keys, chess sets, ivory pegs and bridges for fancy guitars, dice, tea sets, and thousands of other decorative uses are all caught in the downwind. Massive collections, acquired over decades, could lose millions, indeed billions, of dollars in value. By ignoring these interests, Interior’s draft proposals provoked, as The New York Times reports, an “uproar among musicians, antique dealers, gun collectors, and thousands of others whose ability to sell, repair, or travel with ivory objects will soon be prohibited.”

The Pitfalls of Excessive Government Enforcement

Any sensible program that addresses the illegal ivory trade faces serious difficulties in distinguishing between the sale of new and old artifacts. Stopping the sale of these lawfully owned objects unfortunately will do little to nothing to slow down the slaughter of elephants and rhinos. Indeed, the removal of these objects from trade could have the opposite effect. Indeed, the correct strategy may be for countries like South Africa, which have large stores of confiscated ivory, to drive the price down by releasing it into the market.

The strict ban now proposed only applies to goods sold or moved across state lines in the United States. Yet the worldwide implementation of an effective ban requires, as the Department of Interior acknowledges, the cooperation of foreign governments in enforcing the ban in their own countries. The sudden removal of existing ivory from the market will increase the value of new sources of ivory, which will in turn incentivize illegal traders to refocus their efforts to satisfy the huge world-wide demand. It is likely that any ban in the United States will redirect the trade to places like Russia, China, and India, which are likely to prove unwilling or unable to stem these illegal sales. There is no reason to believe that a domestic ban in the United States will have any discernibly positive effect on the illegal ivory trade—and could well be counterproductive.

The proposed ban is perverse in yet another sense: it frustrates the efforts of legitimate firms to grow and maintain herds of elephants and rhinos on private ranches, which could then provide a stable permanent stock for ivory trade. As a 2011 account from the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC)has shown, a far better way to deal with poachers is to encourage and support business entrepreneurs who want to raise wild elephants and rhinos on privately owned ranches.

They will only do so, of course, if they are allowed to sell their ivory in legal markets in order to recoup their costs of production. But once those sales are allowed, these owners have strong incentives to protect their herds from poachers. Private enforcement of property, driven by the profit motive, is likely to succeed where flawed and often corrupt systems of government enforcement fail. But these sales too are subject to Interior’s ban.

Interior’s own detailed proposals list many enforcement measures that can be targeted directly to those individuals and criminal syndicates that kill or trade in stolen ivory. The advantage of this more focused approach is that it avoids the overkill that will occur when and if the Interior implements its regulations on the sale and transport of existing stocks of ivory.

Interior justifies its ban on the ground that skillful parties can forge any papers needed to disguise new ivory as antique objects and thus smuggle them into the stream of commerce. But surely that substitution risk does not justify the ban on objects like guitars that contain ivory pegs and bridges, or pianos with ivory keys, or chess pieces sculpted by master carvers. No smuggler is going to be in a position to make these objects—that will pass muster with collectors—in any quantity. For each spurious object that is stopped, several thousand legitimate objects are removed from the market. Targeting their supposed production facilities should control most of that risk with far less collateral damage, for it is highly unlikely that criminals could devise and maintain the extensive network needed to fabricate small ivory objects.

In light of these considerations, Interior should rethink the scope of its regulations fast. Presently, the government already imposes serious restrictions on the sale of ivory objects, which thus far has done little to dampen the illegal trade in ivory. The free trade in antiques now applies to ivory objects that were fabricated more than 100 years ago. But these objects often need repair, and the new Interior regulations appear to cut off the ability to acquire needed ivory from existing stockpiles.

One particular galling maneuver shows the Catch-22 nature of the proposed restrictions. As is commonly the case, the government requires individual owners to prove that any object that contains even a sliver of ivory comports with government regulations. The proposed regulations appear to require that a piano owner show, for example, that the ivory found in its keys, some of which may be replacements, came in through one of 13 ports that were licensed to receive goods made of ivory.

But these ports did not keep the needed records until 1982. Consequently, the needed proof will be available only in highly exceptional cases. The result is a de facto ban against resale. Clearly other ways to document long possession could be allowed that pose virtually no threat to the government control of the illegal ivory trade. But Interior only cares about small risks of underenforcement, thereby ignoring massive risks of overenforcement. Administratively, it was inexcusable for Interior not to reach out broadly to the industry before announcing its grand intentions last February. No wonder it was met with fierce opposition at a recent Department of Interior hearing from a broad coalition of trade associations and collectors who see the writing on the wall—without making an appreciable dent in Interior’s resolve.

A Constitutional Challenge

Can these industry groups challenge Interior’s regulation on constitutional grounds? As I have argued recently, the correct approach to this question involves understanding the application of the Takings Clause to various forms of government activities. In principle, that approach does not distinguish between “mere regulations” that leave an object in the hands of its owner but subject to restrictions, and a total taking, which involves the government’s taking possession of land or other object. In this case, the removal of the key right to dispose of property by sale clearly represents a partial taking of the subject property. Presumptively, the appropriate measure of damages is the diminution in value attributable to that regulation, which, especially for collectors, amounts to a huge portion of the former market value.

The overall situation is complicated because the prohibition on sale must also be examined in connection with the state’s assertion of its police power, which permits government limits on that right to dispose, which are reasonable both in terms of their stated ends and the means to achieve those ends. On the choice of ends, the government’s case is solid, as everyone in the debate recognizes. But by the same token, the means chosen should be evaluated under a standard that asks whether the future ban is more intrusive than it should be, which this ban surely is. The proper outcome is to strike down these regulations, while allowing the government to articulate narrower rules that give legitimate owners reasonable and effective ways to show that they have not engaged illegitimate activities.

To give but one example, there should be no objection for the government to require owners of musical objects containing ivory to move them in interstate traffic upon filing a simple form that identifies the objects they so own. Transfer of ownership might require an affidavit that urges the provenance of the object in question. But it is just too much to require a chain of title for articles that trade smoothly on eBay or Craigslist. Instead Interior should consult with various industry groups to set sensible regulations that meet constitutional objections.

Under current Supreme Court jurisprudence, however, opponents of this legislation face a stiff uphill battle. In a 1979 decision, Andrus v. Allard,a unanimous Supreme Court sustained The Eagle Protection Act, which in 1962 made it unlawful to "take, possess, sell, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase or barter, transport, export or import" bald or golden eagles or any part thereof. Justice William J. Brennan held that the Act applied to birds whether they were acquired either before or after the passage of the Act.

He then rejected any challenge on the strength of his then-recent decision in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, which subjected regulatory takings—whereby the owner is left in possession of his property but is restricted either in its use or its resale—to far less searching restrictions. In his view, “the denial of one traditional property right does not always amount to a taking,” especially restrictions “devised to resist evasion.” “Moreover, even if there were alternative ways to insure against statutory evasion, Congress was free to choose the method it found most efficacious and convenient.”

The net effect of his reasoning was to give Congress a royal road to do what it wanted in connection with the illegal trade. Distinguishing elephants from eagles is no easy task, but it is worth noting that the ivory ban is a thousand times more intrusive than the bald eagle ban, and far more difficult to implement. But these key differences will only matter if the Supreme Court rethinks its old positions, which it should given the systematic overreach by the Department of Interior. Before any constitutional challenge is lodged, perhaps cooler heads in Interior will reach some sensible political accommodation on its unconscionably overbroad regulatory approach.