The Hoover Applied History Working Group held The KGB and Western Plots Against the Soviet Union on Friday, May 9, 2025.

ABOUT THE TALK

The KGB was no stranger to conspiracies. Actually, it excelled in the genre. The organization was supposed to be different from its predecessors, certainly more measured, professional and rational, but the Stalinist legacy of leveling outlandish charges against groups and individuals deemed hostile to Soviet power was not easy to shake off, not to mention that the organization itself was born of conspiracy. The love affair with conspiracies endured and blossomed even after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Conspiracy came naturally, easily and from every conceivable direction. But how credible were these schemes? Were the security organs immune to their own fabrications? Could KGB officers effectively detach themselves from the fake world they created for others?

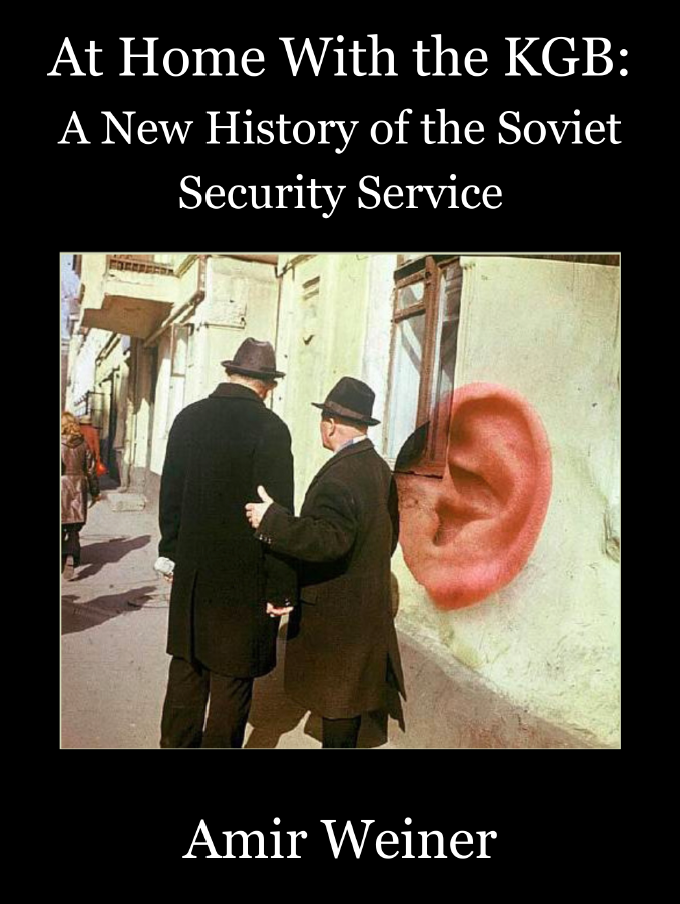

This presentation is a chapter in a forthcoming book, At Home with the KGB: A New History of the Soviet Security Service, (Yale University Press, 2026).

>> Niall Ferguson: Good afternoon, everybody, and a warm welcome to the latest in our seminar series at the Hoover Applied History Working Group. Our guest today has traveled a very great distance from a remote and inaccessible place, the Stanford History Department, and. And he somehow got through the checkpoints and through the Iron curtain that separates the Hoover Institution from that department.

Amir Weiner is, I always want to call you Weiner. Weiner. If you prefer, Weiner, I'll say that. Is director of the center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies and a professor of history here at Stanford. He's a Columbia PhD though his academic career began at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

He's the author of Making Sense of the Second World War and the Fate of the Bolshevik Revolution. But he's here today to talk about his forthcoming book, At Home with the A New History of the Soviet Security Service. The topic, the KGB and Western Plots against the Soviet Union, is a part of the book.

And having read that part, I can tell you that this is going to be a terrific book. Sitting next to him in the role of commentator is Joseph Torigian, who's probably going to correct my pronunciation of his surname. He's a research fellow here at Hoover as well as being a professor at the School of International Service at the American University in Washington.

And he has a list of other fellowships too long to go into. He's the author of Prestige, Manipulation and Elite Power Struggles in the Soviet Union and China After Stalin and Mao, which came out with Yale just a couple of years ago. And he's also about to publish a new book, a biography of Xi Jinping's father.

The party's interests come first, the life of Xi Jiang Zun, father of Xi Jinping. That's coming out very soon. Well, it's great to have you both here. Amir is going to kick this off with roughly a half hour presentation. Then Joseph will comment and then we can all have at it, including those who are joining remotely over Zoom.

Amir, the floor is yours.

>> Amir Weiner: Thank you, Niall, for the kind invitation. Let me start with a few words about what this book is all about, very briefly, and then move to the topic of the presentation today about the KGB and the Western plots to bring down the Soviet Union.

The KGB is the one institution that doesn't require introduction. Everyone knows something, everyone thinks that they know something about it. And in the unholy trinity of the Soviet Union, it is the Stalin Gulag and the kgb. And then comes the question, of course, is there a need in a book about it, another book about the kgb?

And I would say, of course, yes, not only because I devoted almost more than a decade for researching and writing this book. And I would say that most of the accounts that we have on the Soviet security services engage two aspects. One is the Stalinist predecessors of the KGB, especially the NKVD, and quite justly so.

This is the formative years of the Soviet system. This is the most brutal incarnation of the security services that molded the polity, literally, and the population. And the second part, of course, is the espionage, the intelligence, these KGB spying on the west, in the West. And that makes sense also that we'll focus on it.

After all, this is the part of the KGB that had impact on our lives, that spying on our system, on us. And it has all the elements of a thriller. They're always handsome and speak several languages and there's a lot of sex involved and looks great. But I would say that there is also a catch here, that when we look at the activities of the KGB overseas, the abroad, they scored a lot of success.

They had amazing successes against the west in stealing industrial secrets, stealing the nuclear submarine codes, just to name a few. But at the end, it didn't make much of an impact on the outcome of the Cold War, which was their major task, winning the Cold War. And this is something that we have to cope with in general when we study intelligence, and that is the limited autonomy and power of intelligence services in the international arena.

They deal with sovereign states that have their own powers, their own agenda. And also at the end of the day, it is the stability, the economic, social, political stability of the targeted countries that defines its. So the KGB scored a lot of successes against the Americans, to name a few.

Just one country. But at the end of the day, the US was simply too strong, too stable to be destabilized by these KGB successes. Hence my focus in this book. At Home with the KGB is not just a play with words, although I spent a lot of time with these guys in their archives.

But it is the focus on the domestic arena where the KGB enjoyed almost complete autonomy and power over the Soviet citizenry. It was one of the three pillars of the Soviet system. First, one is the political arrangement of single party dictatorship. The second, the command economy, non private property, non market economy.

And the third is some kind of state terror without which the two others would not exist, or at least struggle to exist, as we know after the Soviet collapse. Second, the tale of the KGB is a fascinating story of a force that was compelled twice in its career to restructure itself and dramatically change its course at the height of its might.

In the early mid-1950s, the new KGB is ordered to change complete course and reorient itself. It does it very successfully for the next 35 years. The second time in the mid-1980s, at the height of its might, when it eradicated all internal opposition, it is ordered again to restructure change course.

And this time, it imploded ingloriously. And that raised the question, of course, was it smart? Was it right to compel it to restructure itself? And here I borrow from sociologists of organization. This is the so-called incumbent inertia, when and why it is right or not right to compel a change in course.

Third reason for writing this book. This is a tale of organization that started with universal pretense, ended up in. Pathetic parochialism and is reincarnated as a formidable organization. It starts its career by telling the people it apprehended and interrogates that they would not leave the office or the prison cell without reforming the cell, without becoming a new person.

And they mean it. They tell them that there is no law that prevents them from reaching them. Throughout the globe, we have a global mandate. Forty years later, we find them ordering their agents to activate prostitutes and thieves in order to solicit information from some sailors, etc. And this is at the time when they are collapsing.

So from this universal pretense, we end up with this Titanic going down and the crew is digging in the garbage can. And this is a lot of stories that we can tell about it. But few years later, it is reincarnated under a new regime in the Russian Federation to the point that some of the political scientists call it the transition from oligarchy to spookocracy.

Or I would call it simply from estate with security services to security services with a state. And finally, this is a tale, a fantastic tale of an organization with schizophrenic, distinct and schizophrenic institutional identity. It is an organization that has a universal ethos where everyone counted and everything mattered, which was accounted for.

The unprecedented gathering of information and infiltration of society, on the one hand, and on the other, astounding, astonishing waste, redundancy and loss of focus. In a word, organization that is torn between the political duties, and the professional pride. So, based on a lot of years in the KGB archives throughout the former Soviet Union, dozens of interviews with KGB veterans, and a lot of memoirs they write, they cannot stop writing.

I ask the questions about what was the role of the KGB in the Soviet system? Who controlled it? How the civilian bosses control this organization, how they gathered their information? What did they want to know about the population? Who were the people who provided them with this information?

Who are the KGB officers? Why did they join the organization? How they were trained? Why did they stay? How did they cope with being exposed to foreign information, the one that they prevented and banned their Soviet citizens from getting to? How did they cope with being exposed to it?

How did they cope with the conspiratorial worldview that pervaded the entire Soviet polity? And of course, the issue of how did they cope with the gradual decline in legitimacy of the regime, and the ultimate collapse? And finally, of course, why and how was the KGB, the only Soviet institution that survived the collapse and actually thrived?

What I would like to do in the next few minutes is to talk about their conspiratorial paranoid worldview based on the chapter that in this case, if you can see the chapter seven about their paranoia, and conspiracy theories and ask these questions. Where does it come from? What are the functions of these plots and conspiracies?

And most important, the consequences. The KGB was no stranger to conspiracies. It was producer of some of the most notorious conspiracies, starting with the CIA creating the HIV virus and spreading it among minority communities in this country to many, many other bizarre things that simply makes quite a read and are quite well known.

But it is also a consumer of these conspiracies and plots. But the key question for me at least is were they immune to their own fabrications? Could they stay immune? And here I would like to read a quote from an old hand major general in the KGB and master manipulator himself who posed the question.

Those who exist in a world of manipulation and deception know that it requires an incredible effort to ensure that you do not yourself become infected by the cynicism and cunning involved.

>> Joseph Ledford: Didn't happen to you, did it, Amir?

>> Amir Weiner: Sometimes, but I would say these are wise words indeed.

But could they indeed stay immune to their own fabrications and according to their own creed? They could, because they are a new breed of Czechist of professional security services. They are not their predecessors. This is a highly educated organization. By the end of the Soviet polity, except for the academia, this is the most highly educated institution in the Soviet Union.

All of them almost to the left, they are rational. They work in scientific, rational methods and they're very proud of it. This is an organization that cultivates an ethos of an order, military, knightly order. And they don't use it lightly. This is in their internal decrees. This is in interview, when we sit down with them, they do say, you have to understand that we were an order.

And sometimes you can take the word KGB and simply change it. You replace it with Jesuit, and it sounds very much the same almost to the world. So they're supposed to be different. They're not supposed to fall into this plot. And that takes us actually to the first and what I call the master plot to bring down the Soviet Union.

And we are going to 1945 when this gentleman with a pipe that no need in introduction. This is Allen Dallas, of course in his official photo. But also this is the way the Soviets saw him in the famous cartoon by Boris Yefimov. And here, I would like to read to you the master plot that this gentleman with a pipe concocted and it's worth listening to each words.

We will spend everything we have to bring down the Soviet Union in our disposal to dupe and fool people. The human brain and people's consciousness are capable of change. Having sowed the chaos there, we will imperceptibly replace their values with false ones and make them believe in these false values.

How we will find our like minded people, our allies and helpers in Russia itself. We will gradually eradicate social substance from literature and art, win the artist, discourage them from depicting and researching the processes that occur in the depth of the masses. Literature, theaters, cinema. We all will all depict and glorify the basest human sentiments in every possible way.

We will support and glorify the so called artists who will plant and cultivate in people's consciousness the cult of sex, violence, sadism and treachery. In a world all sorts of immorality, nationalism and enmity between nations will thrive, we will focus on the youth. We will demoralize, corrupt and defile it.

By any standards this is a serious matter and it calls for the KGB for attention. And it is quite an intelligence achievement to gain hold to. To obtain this document, but there is only one problem, a small catch, as we say, Allen Dallas never delivered this speech and there is no such text.

And also, when we read it, the entire document, I just read you a small part of it. It reads like the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and it is not by accident that it is the Archbishop of St. Petersburg who also publish it. And it runs like crazy, like fire in 1992, when it is finally published.

And of course, serious scholars, Russian literary critics, had a field day immediately finding out that this is actually not simply fabrication, but it is also a shoplifting enterprise. It is a work of plagiarism. That the text is taken from a very famous novel, Vechnyy, the Eternal Call, by Anatoly Ivanov.

One of the Soviet literary icons, who himself plagiarized it from another very famous spy genre writer, Yuri, who wrote it in 1964. So, there is a total celebration there in the new Russian Federation but here comes the interesting part. KGB veterans, and I would say some of the brightest and best of them insist that they actually had these documents and read it already in the 1960s.

And the question of, we are talking about people like Filip Bobkov, Viacheslav Shironin. One of them is the head of the analytical department of the KGB and the other is the deputy chairman of the KGB and the head of the fifth Directorate. And the question is, of course, why do they say why?

They insist on embarrassing themselves. And here I would say students of conspiracies often tell us that conspiracy theories now and then manifest themselves and blur the divide between fiction and facts. And the Americans actually did some of the things that ascribed to them in this master plot to bring down the Soviet Union.

Which leads us to take a look at this document as an historical document and with the help of archival research. Should we call it archival scopes that we found in the newly opened archives and some research, it looks less frivolous than it actually sounds at the beginning. We have to ask different questions if indeed this was a shameless fabrication, why did they spend so much time and resources combating it?

Why did they spend so much time not just in verbal oral refutation, but in actual operational plans? And second, maybe, there were other documents that were the basis for this master plot. And of course, the last question that I will conclude in few minutes, the consequences of all this business.

And this takes us to 1962, when the Soviet Union is rocked by wave of demonstrations. This is a culmination of several years of mass demonstrations of Workers, national minorities from 1956 to 1962 and ends up in the massacre of Novocherkassk, June 1962. This is a KGB photo of the demonstrators that ended up with a massacre with the shooting of 26 workers.

This is at least the official numbers, and hundreds of wounded, apparently, the numbers are much larger and this shakes the Soviet leadership, Soviet Union to its core. Quite interesting.

>> Amir Weiner: The internal investigations of the KGB, which was involved in the massacre, not as the main culprit, but it was there on the ground, and it was in charge of investigating it.

They do a real job, and they conclude that most the agitation of the workers were demonstrated because of the declining living standards and wage cuts, etc. Were genuine poor management, poor living standards and they reported. But very soon, almost immediately, in few weeks, we see a different change.

And now the blame for this event, this eruption is laid directly at foreign intelligence services who activated these people. And these Soviet workers are actually foreign agents with dressed in workers shirts. This is the official language that is being used here. And there is something interesting that happens at the very same time when we read the internal memos of the KGB at that time.

And in 1962, a guy named Allard von Scheck, a German publicist, quite famous at the time in Germany, one of the founder of Group 47, very famous literary group in post war Germany. And a diplomat who joined the foreign service shortly before, published an article on the spiritual struggle during the age of coexistence.

And it's worth listening to what he says, because remember, we already listened, and you have to listen to me reading Alan Dallas. And he writes in his piece with all the media and modern propaganda and smart psychology. Our ideas of the west should be smuggled into the public life of communist states, making use of the national differences, religious traditions, human weaknesses, curiosity, female vanity.

Desire for entertainment, indifference must be encouraged towards the goals of the communist state's management. The economic, moral and other shortcomings characteristic of communist state management must be mercilessly exposed so that the population should adopt passive resistance. And if the communist state should make more punitive measures against one or another person, we should publicize it in order to gain sympathy against this unjustified persecution.

At congresses and enduring journeys or other occasions, we must establish contacts with intellectuals of the communist states. We should not avoid disputes, correspondence and cultural exchanges. Because the west has confidence in it that the youth of many communist states will alienate themselves simply through acquaintance with the outside world, it goes on and on, etc.

But this is what we call it is published in a very famous journal in German, by the way. The KGB refers to it as an American newspaper because there's always a center of conspiracy there but this is what we would call probably an op ed nowadays. But the KGB takes a note, and it doesn't refer to it as an OPED.

This is a master plan, the one that they always suspected existed, and if it bore some resemblance to the so-called Dulles speech, it is not by accident. And in a lengthy rebuttal, this guy there, Michael o' Nell, Yevgeny Aleshin, takes issue with this. Not only to refute the allegation, the suggestions, recommendations by Allard von Scheck, but also devise plans.

Operational plans to combat it. And what we see cyberside immediately the emergence of an official line inside KGB reporting in operational plans and memos, inside organization and to their civilian superiors, that domestic enemies are now being referred to as paid foreign agents. And the numbers, not the issue, just their existence.

And here, in speeches by Nikita Khrushchev, who delivers several very verbose, as usual, very vulgar speeches on issues, almost taking issues with a large phone check, item by item, point by point. They are domestic opponents are referred to as paid foreign agents that even two or three of them will act incorrectly are extremely harmful.

And he refers also to his favorite metaphor of Taras Bulba. That Joe here certainly is familiar with Taras Bulba. Nikolai Gogol, the great author, who talks about how Taras Bulba killed his son because he went to the other side. And this is the recommendation of the Supreme Soviet leader at the time.

And there is a difference. This is from other previous eras in the Soviet Union. Excising the domestic enemy is an old Soviet trope. The Stalinist always did it. But here comes the difference. It is one thing to refer to Ukrainian nationalist guerrillas as pawns of the Nazis or the American security services.

It is one thing to refer to Catholic believers or Eastern Orthodox believers as points of the Vatican. It is utterly another to refer to Soviet youth, Soviet intelligentsia and all other Soviet workers as foreign element to be dealt with as paid foreign agents. And what we see from 1963 and on, again, I will not labor you with this for the sake of time.

We see that KGB tasks itself with the goal of analyzing, exposing and eradicating and underlining the true sources of deviations. We can ask ourselves, are there conditions to do that, to actually find the true sources of apathy, boredom, resentment in the Soviet Union entity? Are they conditionally. This is a secret organization, security services, but we have to remind us that this is a political police which has different mandate.

But what we see, in any case, through one organization operational plan after another throughout the branches of the KGB from early 1963, we see the radicalization of activities surveillance of these groups of youth, intelligentsia and the workers. And the rhetoric is becoming paranoid, that literally creating almost hermetically closed fortress.

The rhetoric is also now talking about radicalizing the struggle against domestic enemies. And this is taken directly from the Stalinist metaphors, that as we approach communism, the struggle is becoming more and more radical. This is quite interesting, because this is also the time when the Soviet Union is opening up to the world.

More and more foreigners are coming, more tourists and Soviets are going. So there is quite a problem and quite a challenge here for them. This is the time also when the KGB is offering making recommendations to its civilian bosses, the party leadership, to create a ministry of propaganda and ideological communications.

If that sounds a little bit familiar from present day, take a guess that this is coming where it's coming from. But they also sowing the seeds here of the future 5th Directorate, the Piatr Uprevlenia of the KGB to fight dissidents and ideological deviation. Already at the time, several years before that, paranoia is taking over.

We see also the KGB now feeding artists and writers with this information. And that's how we come to one of the famous novels of Yuri Doldmihalig, whom I mentioned earlier, who uses this text of Allad von Scheck almost verbatim in a monologue that he plants in the words of his protagonist and American general, whose name is, by the way, General Dumright.

Quite a choice of name, but it is now going over beyond the KGB now to the Soviet public, etc. And we see that now it's literally all the way down the rabbit hole. This plot thinking is taking over very tight grip over the KGB thinking and operations. In 1977, to give just one example, Yuri Andropov delivers a very famous memo that was published immediately after the Soviet collapse to his bosses.

It's 1977 about the CIA plot to recruit Russian, convert them to Western ideals in order to sabotage the Soviet economy and install Western ideals, convert Soviet managers and leaders into Western ideas. Taking a leap to 1988. This is already the time of perestroika and glasnost. The KGB now goes public, its publishers now it's part of the new social media or the new free media.

And in an article in 1988, it informs the Soviet public, still Soviet public, about a conspiracy of the CIA that was articulated in a recent conference with leading Sovietologists and the CIA. How to destabilize perestroika, to simply to derail it, with the help and coordination with the German and the French security services and certain dissidents outside of the Soviet Union, so on, so forth.

And this is literally the words of Alaud Fonscheck, simply reworked a little bit again and again. Here I would just make a note before concluding, talking to many CIA veterans and Sovietologists who are still alive and active. Nobody remembers any such conference that was held. And certainly just the thought of collaborating with the German and French intelligence on such things was quite an anathema to them at the time.

Nevertheless, this is the story. So what is the rationale in conclusion of this obsession and fixation with the plots, with the master plots and conspiracies? For one thing, it makes sense, it offers the KGB self offer, The higher moral grounds against their arch enemies. Second, it's a justification for the continued persecution of domestic enemies after the renunciation of Mester or after Stalin's death.

But whatever the reasons are, the outcome was catastrophic for the Soviets themselves. Because the obsession with a non-existent master plan led to inevitable deviation from a clear eye view of the actual roots of the problems, of the system's problems. The KGB was well aware of the issues, it discussed them in details, it informed the party authorities and it was in constant communication about the problem of growing apathy among writers, youth, the atrophy of revolutionary idealism.

They are aware of it, but they are always in two minds. One is as they admit many of them, whether it is Vladimir Semiechasti, the chairman of the KGB at the time in the 1960s, or Vladimir Kruchkov, the last chairman of the KGB, they admit that at the end of the day, the fate of the Soviet polity was depended on our internal situations.

But the western intelligence services also had a major role in bringing us down. And at the end when they calculate, they put all these calculus together. It is the second component that takes over as the decisive factor. And this is with catastrophic results. Because when the time comes and the KGB is called to protect and save the Soviet polity, when it begins to crumble, this is exactly when conspiratorial mind is self defeating.

And here, just one final quote. Few months before the collapse, when the Soviet Union is already rocked by ethno national violence and the KGB is conducting surveys as it used to do during its final throws, a lot of internal service among its cadets and officers about what they think, what are the main major challenges?

And this is from June 1991 internal survey and the question that was posed to several hundred of them. Do you know why things are bad in our country? And here are the answers. 77.6% of the officers said sabotage, 19% said that they are confident that the enemy's special services purposely frustrate our plans, 42.3% place the main responsibility for the aggravation of national relations on hidden forces and 40% of them blame foreign nationalist organizations.

Conspiracy comes naturally and easily from all directions. But understanding the enemy's intentions was just another excuse of avoiding the existential homemade problems. Thank you so much.

>> Niall Ferguson: Thank you very much, Amir. I'm going to hand straight over to Joseph Turidjian for his comments.

>> Joseph Ledford: Well, it's a real honor to be a discussant for you, Amir.

You'll remember when I was a pre doc at csec, an Interloper from MIT Political Science Department. You took me seriously, and I'll always be grateful to that. And in fact, a very serious component of the theoretical argument of my book was based on some comments you gave to me about needing to take ideology more seriously.

And so you, I'm sure you saw yourself when you saw the finished version and this forthcoming masterpiece, Samir, really has taught me to think even more carefully about ideology and other issues that interest me. At heart, your book is a history of the second half of the Soviet Union through the prism of the KGB, one of the most mysterious and significant foundations of Soviet rule.

And you do that in two ways. One, how the KGB reflected changes in society, but also how the KGB impacted the trajectory of Soviet history. And you touch upon a perennial debate about the Soviet Union, one that maybe this audience isn't fully familiar with, but there were some individuals, including people as different as Andrei Sakharov, but also the Russian historian Yevgeny Al Bats and the British historian Christopher Andrews, who saw the KGB as a potential for good.

Who saw them as a set of individuals who, because they were better educated and because they had spent time overseas, were potentially a reserve force who could push the Soviet Union in a direction that is exactly the direction that you argue that they move towards. So you're picking up on a historiography that our audience might not be fully cognizant of.

Your book is also part of a very exciting trend in the study of the Soviet Union, one that draws upon new materials and asks big questions. We've already had Yaakov Fagan here at the Hoover History Lab, who talks about the back half of the USSR through an economic angle.

And we've had Benjamin Nathan's come in to talk about the back half of the Soviet Union through the lens of the dissidents. I feel like your book and his book will be very interesting compendium for each other to be read together to see how they viewed one another.

And one of the reasons I like your book so much is that it takes these. Makes these big arguments, but it frames them in a way that rests on narrow empirical questions that are then very persuasively answered with the evidence. So I'll limit myself to three very brief thoughts.

The first about how your book reveals a very interesting contradiction at the heart of Soviet rule that you answer by saying that was never fixed because of a pathology in this conspiratorial worldview. And I'll do a devil's advocate to suggest that maybe they weren't fully wrong about one way of solving these problems that ultimately rested in an equilibrium that might have proven to be more persistent.

The second is to push you along little bit on how exactly the KGB served as a conservative force, especially through the lens of elite power struggles, and whether they manifested as a bureaucratic interest. And then I'll conclude just with a couple of very brief points on China, and I'll do that within 10 minutes.

So the interesting commonality between your book and Yaakov Fagan's book is they're both rooted in this realization by the Soviet leaders that after the introduction of nuclear weapons, the competition with the West was going to change fundamentally and that these contradictions were no longer going to be resolved by war.

So economically, what that meant was competition with the west to show that the Soviet system was superior in its ability to provide goods to people. And ideologically, it was a very different story. Ideologically, it was, okay, they're not going to invade us because they're too scared, but what they're going to do is engage in ideological sabotage and because we no longer have class interests within our society.

What that means is whenever there are any problems, it's because the west is infiltrating us and creating these challenges. But what's interesting is at the same time that this very reactionary view is emerging, you're also seeing Khrushchev trying to shift to a less fraught. State society relationship, where you see Khrushchev talking about socialist legality, that Khrushchev was in fact a great skeptic of the kgb.

You already referenced this wonderful quote where he calls them basically the party's son. And of course he's comparing that to Teresbalba's son, who said that I created you, therefore I can destroy you. He promoted people from outside the KGB, Toleda, Shelepin and Semichastny. He wanted to split the KGB into a rural and urban force.

He wanted to turn them into a professional union, which meant that they would no longer even be able to work military. He didn't promote generals. He wanted to cut the size of it. And he talked all about departing from these abuses of the Stalin era. Now, what's interesting is Khrushchev also had very hard-line elements, and so people think of him as a de Stalinizer, but they forget about this extraordinary speech that he gave at Manoj, which you referred to, where he talks about people who spit on Soviet society and all of these rather gendered and colorful ways.

In some ways it reminds me of Deng Xiaoping, where people think Deng was a wonderful person, and they forget that he also had this view of peaceful evolution that was quite reactionary. So you have this really interesting contradiction, right, where on the one hand, the Soviet regime wants to pretend that it obeys the rule of law, and the KGB like to think of themselves as professionals, but.

But at the same time, the regime is seeing a threat in behaviors that are not technically illegal, only ideologically suspect. So you mentioned the Andropolov's 1977 memo, but he also has a very interesting speech in 1967, which I'm sure you've read, where he says the problem is that people aren't breaking the law.

It's that they're behaving in a way that doesn't break the law, but that might allow them in a future date to break the law in a way that is very dangerous, which means that we need to police their ideological thoughts. And so how you do, how you police people who aren't breaking law then becomes a very fundamental question.

Because if you use these prophylactic measures, if you send them to insane asylums, if you internally exile them, none of those are actually legal according to the Soviet Constitution. And in fact, criticizing the Soviet Union is not technically illegal either. So how you proceed from that was something that the KGB tried to figure out.

And what ultimately happened was by the late 1970s, early 1980s, this cat and mouse game finally concluded with a decisive annihilation of the dissident movement. It's very interesting that it happened, by the way, right before perestroika and glasnost, and that none of those dissidents, or almost none of them, played a role in that movement, which may be something you could think about, but the question becomes, why did they go through that song and dance routine?

And it seemed to me that it was a policy in many ways of dithering, right? Because you're not doing it from the Stalinist, Maoist approach, where you really don't allow anybody to ever even pretend that you're not loyal to the regime that you just had these constant campaigns of state terror, which North Korea has apparently been able to do for like three generations now, right?

And in fact, what's interesting is, as you mentioned, the Soviets compared themselves to the Chinese as being less barbaric because they weren't using Maoist methods. And they kept saying, well, just think of what we would do to you if it was the Stalinist era. And they sort of took pride in this, right?

And you can see how maybe in a way you could win over people by pretending in this way, but at the same time, it created a lot of confusion and doubt, and it took them so long to crush the dissidents, and they looked so terrible in the meantime, because nobody believed those trials, which is kind of ironic because those trials were somewhat more serious than the ones in the Stalin era, which were a total farce, but the farces were better believed than the ones that were not.

So my question is, could we imagine a world in which the Soviets did successfully move to a new equilibrium in which the rule of law was actually established? Why exactly was this impossible? Was it a legitimate and reasonable fear of a legalized opposition that really would have destroyed the USSR, Meaning that maybe even if the United States wasn't engaged in peaceful evolution in the way that they were inferring that maybe treating the situation as such was necessary because as soon as you create any opening in society, it will metastasize and destroy the regime.

So that's not a story of paranoia that's the story of talking about the problem in a particular way that's useful, whether or not it's actually fully rooted in the nature of the problem. And so, the other question is, if the hypocrisy was so obvious, why did they pretend with the socialist legality?

Why didn't they move fully more in one direction or another? My second comment has to do with the role of the KGB in power struggles. So you're talking about, like, how the KGB actually affected society. And one way to think about it is, you know, you describe these folks as, like, real Jesuits as a guild, but that's what the Bolsheviks are supposed to be in the first place.

Right? Like, that's what the communist part of the Soviet Union was designed as, as an organizational weapon when you read Philip Selznick. So now you have an organizational weapon within the organizational weapon that is trying to behave like knights in a way that they're sort of guardian of the revolution more than the people who created the revolution.

So what does that mean for the trajectory of Soviet history? And so you're saying that they had a particular worldview. Well, was that worldview so different from the Party worldview? And why did they have the different worldview? Was it an education story? Was it a recruitment story? Was it an empowerment story?

Was it a sense of superiority story? And then if they did have this worldview that was very different from the Party, how did it manifest? Right. So when we think the KGB was so decisive in every power struggle that ever happened, this is something both of us know so well.

Serov in 1957, Semichastny in 1964, the role of Andropov in the rise of Gorbachev to power, the role of Kryuchkov in 1991. In every single one of those cases, everyone fully understood that whoever side the KGB picked was decisive. But it doesn't seem that the reason the KGB picked one person over the other had to do with this broader worldview story.

But more often, either because they thought that the leader was going after them and they needed to move first, or it was much more narrow institutional reasons. And so if that's the case, then is it because of the information that they're feeding? Is it because of a fear of the kgb?

What is the mechanism there, exactly? And finally, when it comes to China, I kept chuckling when I was reading your book, because Andropov and Bobkov and Strunnikov and Alyoshin, they sound so much like Xi Jinping. They sound so much like Xi Jinping. And so there were these speeches that were leaked to the west where he gives.

Where Xi Jinping is talking to the military, and he says that the west will become increasingly brazen in its attempts to defeat the People's Republic of China for ideological reasons, but it's a war without gunpowder, because they're afraid of us. And he talks about peaceful evolution, and he talks about Dulles, Right.

And he refers to a speech that Dulles actually gave. So Dulles might not have given this particular forgery, but he did talk about that and all of this stuff about Bill Clinton in the 90s talking about bringing them in to American global order to transform them. Well, if you read the people surrounding Xi Jinping, they say that was working.

They say peaceful evolution was working. But thank God, Xi Jinping, who was able to draw upon the characteristics of the organizational weapon, the real legacy and heritage of the revolution, this vigilance and struggle mindset, and was able to turn things around. Now, what's interesting there is that the political police never played a role in Chinese history like they did in Soviet history.

And so, in fact, strangely, on one occasion, Chuni, during the Cultural Revolution, he was asked whether they were going to kill all the people who were purged and he poisoned. Pointed to the Soviet delegation and said, we don't do that. We're not like the Soviets. And in fact, during the worst terror, their domestic political police were almost completely destroyed.

Right, it was a different kind of persecution. So, but just as a final code of this, it does seem to me that, the Chinese are also in this, went through a very similar trajectory as the Soviet Union, where you had during the 90s and the 2000s, a group of dissidents trying to make the Chinese regime do what it said it was trying to do and say, we need to obey the Constitution.

And then by 2008, with the OA Charter and Liu Xiaobo, that equilibrium was destroyed. And then there suddenly became no space. It was kind of, it was almost exactly the same kind of thing that happened in the Soviet Union. And then now they're kind of in this muddle.

And so the question then becomes, is there a political police in China or who is it in China or is it really just like not so much a KGB political police thing as like a Bolshevik thing? So I'll stop there.

>> Niall Ferguson: Thank you, Joseph. We have just 25 minutes of time left, and I suspect there'll be numerous questions in the room and online.

So I urge you to respond briefly to Joseph, and then we'll open it up to the floor.

>> Amir Weiner: Thanks so much for the great, great comments. They indeed, they can take three hours to answer and 700 pages of manuscripts but I'll be very brief about them. The KGB is a conservative institution by definition.

It is to protect the party. And second, stability. Stability in society, in the Soviet polity. It is not the fermenter and originator of Maoist style revolution. Actually they are born, they literally cannot stand Mao, not in their communication and expression, etc. This is almost a frightening scene, what is happening just across the border in China.

The way they look at these crazy speeches and they refer to him as crazy at the time. So they are conservative by definition in the few times that they participated in public. I'm sorry, in power struggles, 1964, the motion of the dismissal of Khrushchev and 1991, the failed coup, et cetera.

It is actually to preserve stability against people who try to reform or move the system in a direction that it is not so much the ideology behind it is the instability of that they created. So the KGB is conservative organization by definition and by operation. Second, the issue of the self contradictions, yes, they have to live with it, with the new or the return to socialist legality, which is a concept that goes back to the 1930s, after the mayhem of the so called great breakthrough.

But they tried their best in this sense to work within the law and things that I have not talked about but there's long, long chapters about war crime trials of especially nationalist, anti Soviet nationalists. And we see the KGB there operating not simply by the law, but also in a very professional way and professional standards that would not embarrass any Western specialists and jurists.

They walk by the door, they investigate real investigations, they decipher letters, they have forensic examinations, they try to do to live up to the new standards, because they are not their predecessors, they are not the bone breaker. This is one of the things, by the way, that when I sit down with my guys, I call them now, I once refer to them my gangsters.

And someone corrected me that no, we were not gangsters, he's still alive. But the one thing that comes again and again, we were not the encevedi. And one of them goes even further and say we were not the Gestapo. And others who have more flair for history tells me we were not the Inquisition.

And who today accuses the Vatican of being responsible for the inquisition, etc. So they are very much aware of this. But two things happen. First of all, there are political police. And this is already an extrajudicial component to it. Second, there are like the rest of the civilian bosses, that are frustrated, increasingly frustrated, their ongoing campaign to eradicate the remnants of capitalist bourgeois vestiges, etc.

And they don't succeed for a long time. It creates a lot of frustration, despite all the might but here, I would say something here about the dissidents. They do demolish the dissident movement by 1980, it doesn't exist anymore in the Soviet Union and the KGB does something that is quite unique for a political police.

They declare victory. They declare victory. And this is the one thing that they cannot allow to declare victory, their own d' etre is the existence of. But nevertheless, in their annual reports they celebrate we eradicated this movement, which tells us something, so they are not so much afraid of the dissident as an organized movement which they demolished.

It is the ideas that are there still and very important for them. I would say just one thing about their issue of a vehicle for reform and legalization, etc, I would say, yes, they view themselves as the best and the brightest. They are not so humble when you talk to them about it.

Two things that comes immediately to mind when you talk to them, when you read their documents, internal communications. One, they are very Anti Western. Forget about anything else. That they can work by Soviet law. They can try their best to adhere to legal norms. They do not torture people.

I can give a lot of evidence of them telling people that. My gosh, few years ago I would have convinced you that your grandmother had balls, pardon the language. But now I don't do that. So they are actually very proud that they don't beat up people. But the anti western is there.

They don't like. And until present day they don't like the West. Forget about it. That they wanted to be like us. That they really, if you just gave them a chance, they would have become a second us. Not at all second. They have strong resentment against the party.

Not because they are anti communist or in the fact that almost all of them are party members but the party aparaki are anathema to their ideal. They are corrupt, they are manipulators, they are lazy. We are the hard-working people, we are not corruptible. And again, this is self image, which was not always true, but much better than the rest of institutions.

Until they get to fight organized crime. And then they are exposed to big money and the collapse of the Communist Party and when they inherit literally all their accounts and then things go south with all of them. But they don't like the party. The party are simply parasites.

I will stop here because it sounds.

>> Joseph Ledford: Like they identified the problem pretty well.

>> Amir Weiner: All your questions are great questions. The comparison with China is on the mark because this is not just a Soviet problem; this is a communist problem, certainly.

>> Niall Ferguson: So let me invite questions from the floor if you want to attract my attention.

There are various ways of doing this online. You can raise a virtual hand in the room. You can just raise a flag. So Philip was first to move, so he can go first. But please try and attract my attention and I'll try and keep track of all the people who want to intervene.

Philip.

>> Joseph Torigian: Okay, thanks a lot. Niall, Amir, thanks a lot for a very interesting presentation. And Joseph, thanks a lot for excellent discussion. I'm writing a book about KGB education, KGB training schools and universities. And one of my arguments is that the resilience of the KGB is to be found in the way they educated their recruits.

So my question, Amir, is what's your take on that? What I'm arguing is that the way they organize their educational system, their special educational system, their training schools, their universities, their research incalculated a very strong sense of identity and commitment to their organization. And this is what led them to be able to essentially survive the troubles of the Soviet collapse and reincarnated themselves in what you said, I mean, a secret service with the state in Russia today.

>> Amir Weiner: Yes and no on this one. When you read their educations, which, by the way, they are very proud when you talk with them. They are very proud and very nostalgic about their time of education. Very few of them dismiss the idea, it is not serious, etc. They are educated there.

They are trained as professionals from everything from deciphering secret writings, handwritings, to handling guns, machines, spying, recruiting people, but simply professionals being trained as professionals and. But also indoctrination. Some of them said that it was a little bit over their head. They didn't pay attention. I'm not so much about it.

They learn languages there. They are one of the very few organizations that are trained in foreign languages. Not that exactly they speak the language of the bad that fluently, but this is one thing to remember. But they also taught conspiratorial thinking there, not just by the profession itself, but when you read, and you probably read a lot of what they were, the lectures that they listened to and the articles that a lot of Zionist conspiracy.

By the way, there is an obsession with the state of Israel, with the Mossad, with the Zionist organization all over. They simply cannot have enough of it until 91 in 1901. One of the last lectures in the higher school of the kgb, the Dzerzhinsky school in Moscow, is about Zionist plot to bring the Soviet regime in the 1920s.

Not to mention that there is a very strong element of antisemitism in the lectures that we see from their notebooks that they took during the lectures and you read about the Jews are to blame for everything, for the failure of perestroika, for the calamity of the White Sea Canal, so on and so forth.

But the key for their survival there, I would say it's not only the sense of professionalism, it's the cohesion of the organization. They literally had each other's back. This is something that is cultivated with rituals, constant rituals. It sounds a little bit over the top, but the KGB officer is almost like a father figure in the unit, very often of taking care of the welfare, the well being of the recruits, etc.

And they remember it very, very fondly. And when they collapse and they are under the gun, because during glasnost and perestroika, the KGB turns into the pinata of the new media. Every Monday and Friday there's a new charge, a new accusation of brutality, criminality, et cetera, et cetera.

A lot of cohesion closing ranks in non Russian republics when the system collapses. Veterans of the KGB do not get their pensions from the States. They are deployed for the years during the KGB. So take a guess who pays their pensions. The FSB, The Russian Federation. So there is a tightening and they do take care of each other during the collapse from 1990, when going south and the economic situation deteriorates, you see that commanders have influence and connections take care to find jobs for the departing officers.

So I would say this is the key for their survival.

>> Niall Ferguson: Philip Zelikow next.

>> Philip Zelikow: So I want to return to the issue you opened up with at the start, which is the issue of intelligence versus self deception, which is you have, I think, these very vivid descriptions about attributing domestic descent foreign plots.

I asked myself, when in Soviet history do they not attribute domestic descent to foreign plots? I mean, the elaborate choreographies and the scripts even of what surely I mean the interrogators knew, were fantasies that they were constructing in the interrogation rooms, which is flowering by the midnight, by 35 and afterwards, but appears to more or less be endemic from at least that time on to 1991.

And so like, is there any time when this subsides? And they actually are. And here's where your Nova Cherkass story really punches out, because I think you describe an episode in which they're actually gathering some useful intelligence about what was really going on there. And then the switch flips and it becomes a foreign plot story.

And so the hypothesis, here's what I'm taking away, is intelligence versus self deception. Self deception is basically constantly winning with deeply pervasive corrupting influences on the sword and shield of the vanguard, which is how they think of themselves. But then a further wrinkle on that in your Novochar Costa story, which is field people at first may think they actually want to know what's really going on here.

Until the party basically says, adopts the line. And so Norvar Shirkasta come and say, well, here's actually some useful reports about what was really going on here. And then the party actually flips the switch and adopts the line. That's what this was. And then of course, that will reverberate all the way back downward, including to the field, and with effects that are hard to imagine on the people who are actually on the front lines.

>> Amir Weiner: This is an inevitable question, the most expected indeed. The Soviet polity is a conspiracy, they do believe in conspiracy. And in a way there is some justification there for this. The west did try to destroy them, period

>> Philip Zelikow: And had psychological strategy boards and.

>> Amir Weiner: All this information is not buried, it's highlighted there.

But certainly they do a lot of the things that ascribed to them. And of course the best example is the 1930s, the trial of the Trotskyite Bukharinite, you just name it, all of them. They found that Jews were working for the Gestapo and Trotskyite were wrecking the industry that they built, so and so forth.

And with the help of torture, everyone confessed to this. Those who did not died in any case, so it doesn't matter. But two things that makes it slightly importantly, I would say differently. There is an attempt to move away from this after Stalin's death. The repudiation, the renunciation of all these master plots.

First and foremost, the doctor's plot, the charge of the accusation of Jewish doctors plotting to assassinate the Soviet leadership, and so many other things. There is an attempt to move away from this. There's also an opening with the West. We can cope with the west, we can coexist with the west for a variety of reasons.

The most important of course is the nuclear era that they're understanding, etc. What is happening with the KGB is that we see falling back into this idea of the agent of influence and foreign based agitators, especially two things. One, the search for master plot, for the overarching conspiracy that even there did not exist in the preceding eras.

The masterpiece that it must be this diabolic master plan to bring it all together, etc, that you can find indeed some elements that were indeed taking place, but do not echo gel. And second, it's supposed to be different. They supposed to be, as we already mentioned, rational, professional, scientific about it.

And it's interesting that it starts not only with the party, this point, our guys, the people that we created, Soviet youth, Soviet intelligentsia, Soviet workers. It's also with the KGB. And for instance here, this going back to Novocherkask. The first accusation comes from the local KGB boss in Rostov.

He said, certainly there was the elements of a foreign agent inciting the people. So this is partial answer.

>> Philip Zelikow: The switch is flipping here in June 6th. So after 53, where they're pulling back on this. Do you think the switch is flipping here like with and then the dissonant movement and all the rest?

>> Amir Weiner: Yes, I think that there is this correlation of what we call the perfect storm that is happening. And this, by the way, this is the culmination. But this is an event that shook them to their bones. The fact that people were shot, 26 people after three days of the demonstrations, this is a very famous event.

By the way, there's a great movie that years ago, Comrades, that highly recommend very, very Close to the Facts, a Russian movie excellent about these events, including the shooting that happened there. But this also happens at the same time there that this guy that most people don't even know who he was nowadays in Germany, even in Germany when I came across his stuff and I investigated and people simply said I have no clue.

He was a specialist on Buddhism, but he was also a diplomat. He writes this op ed and this guy is one of the first and the KGB takes it as an operational document, not as an op ed, etc. So I would say this is probably the best unread op ed in history that had so much impact.

But of course this is not the only trigger that happens there but it is a catalyst of many of the changes.

>> Niall Ferguson: Before we run out of time, we've got Robert Servus on the line. Robert, I hope you were able to hear Amir who's studied the KGB for so long that he now speaks in a whisper for fear of being picked up on the microphones.

>> Joseph Ledford: Robert.

>> Robert Service: I know the prehistory of Amir, yes. Yes indeed, that's a fascinating talk. Amir, I was wondering what you thought about this. You've told us about the prevalence of a paranoid approach to the Soviet social scene in the 50s, 60s and 70s. I wonder if it was.

Well, I just would like to know what you think. One way of looking at this would be to say if the small party takes over a country and says no religion, no private enterprise, no opposition, only dictatorship, is it only paranoia to suspect there is going to be a, an undercurrent of profound and deep opposition always, not just in the 50s and 60s, but right the way through the Soviet period.

So to that extent you could say, for example, that the use of the secret police in Stalin's period was not just paranoid, it was a reaction to a, to a realistic perception of opposition and moreover that the idea, what I'm getting at is that the Soviet system was always more brittle than many Westerners assumed it to be.

Was the KGB reflecting that, or was it exaggerating the reality? How stable was the Soviet Union in the period that you're looking at and I'm sorry I look blue in the face, it's because it's late at night here.

>> Niall Ferguson: Thanks, Robert. I actually noted as I was reading the manuscript that some of us got to look at you write Amir, if espionage had been central to the Cold War, the Soviets would have won but they did not take the KGB out of the equation and the Soviet system would not have endured the post Stalin era.

So I take your central thesis to be. That it's indispensable to the survival of the system domestically?

>> Amir Weiner: Absolutely, certainly. But there's always, when you talk about the KGB on the Soviets, there's always but. And I would say the Soviet Union was stable to the point that there was no existential threat for most of the time for the communist regime.

There was no organized opposition capable of, of bringing down, changing the system. The worst that they faced was in the western borderlands in the post war era, the post war civil war, when they actually faced close to 100,000 Ukrainian nationalists on the ground and 20,000 Lithuanians. And this was a bloody war.

And at certain points for several months and actually close to a year in 1945, 1946, they controlled these territories, the anti Soviet guerillas, but they demolished them in the worst brutality that you could imagine. They went head to head, toe to toe, and they eliminated them physically or deported the rest to the camps, etc.

The main story here is that the KGB is simply a child of 1917 and 1956. Mainly. What do I have in mind? They learned from their own understanding, is that a small organized minority is capable of doing a lot. If you take a look at 1917, the Bolsheviks are certainly not a majoritarian party.

They're not small, but they win about 24% of the elections, the last three elections in the land of the Russians and. And they take over. They take over in a pooch that they called the Great October Revolution. And it's a lesson that an organized minority can do a lot.

And they are working throughout their career to prevent it. 1956, when you look at the worst calamity from the Soviet point of view, in Hungary, In Hungary, in November 1956, for a few days, a communist regime collapsed. And Soviet citizens, and especially the kgb, who is on the ground involved in suppressing it, watch it very closely, participating in the suppression.

And it all started with demonstration of Hungarian students in Budapest, that from their logic, if you let an organized few to gather momentum, the end is bad. So that's what they're working all the time. But I would say that after 1950, probably after 1949, there is no organized opposition that is capable of bringing down this regime.

The change starts when they begin to loosen up under Gorbachev and it's beginning to gather momentum. A lot of this has to do with his own mistakes. But also there is the catalyst, especially in the western borderland, in the Baltic states in particular, all these territories that were annexed in 1939, 1940, and they were parts of sovereign states.

There is a problem there of digesting them and Sovietizing them. So this was a combination at the time. So long answer for a short question, but this is indeed the fate of the Soviet Union.

>> Niall Ferguson: Thank you. We are unfortunately out of time and I don't want to detain people who have commitments elsewhere.

I was struck, as you were describing, the conspiratorial mindset by the mirror image that persists to this day, based on the testimony of the defector Yuri Bezmanov, whose interview from 1984 still does the rounds, showing, or apparently showing, that there was a Soviet plan to subvert the west, and particularly the United States.

And this is the sort of counterpart to your House and Politik Oped. I actually don't even know if Bezmanov really was a KGB agent or just pretending to be one. Do you know, do you touch upon him in the book?

>> Amir Weiner: He was an officer, but it's not really clear what's happening with him.

It's not clear. And he ended up really badly, he, I think, committed suicide. So he wasn't happy in the west, that's for sure.

>> Niall Ferguson: Continue to watch that video and quote it as if it really was the Soviet master plan. It's two superpowers in search of conspiracy theories against themselves.

Thank you very much indeed, Amir. Please join me in thanking both Amir and Joseph.

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Amir Weiner is the Director of the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies and a Professor of History at Stanford University. He is the author of Making Sense of War, Landscaping the Human Garden, and numerous articles and edited volumes on the impact of World War Il on the Soviet polity, the social history of WWII and Soviet frontier politics. His forthcoming book, At Home with the KGB: A New History of the Soviet Security Service, will be published by Yale University Press in 2026.

ABOUT THE DISCUSSANT

Joseph Torigian is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution; an associate professor at the School of International Service at American University in Washington, DC; a global fellow in the History and Public Policy Program at the Wilson Center; and a Center Associate of the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan.

Torigian was previously a visiting fellow at the Australian Center on China in the World at Australian National University; a Stanton Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations; a postdoctoral fellow at the Princeton-Harvard China and the World Program; a postdoctoral (and predoctoral) fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation; a predoctoral fellow at George Washington University’s Institute for Security and Conflict Studies; an IREX scholar affiliated with the Higher School of Economics in Moscow; and a Fulbright Scholar at Fudan University in Shanghai.

His book Prestige, Manipulation, and Coercion: Elite Power Struggles in the Soviet Union and China after Stalin and Mao was published in 2022 by Yale University Press. His biography on Xi Jinping’s father, The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping, will be published in June 2025 with Stanford University Press. He studies Chinese and Russian politics and foreign policy.